Translating the compelling logic of economics into actual climate policy is no small endeavor. It takes years of political organizing and movement-building.

At the heart of this effort is the Citizens’ Climate Lobby, which since 2009 has been building political will for taxing climate pollution by educating and activating voters across the country and engaging elected officials. CCL has grown almost exponentially and has placed hundreds of pro-carbon tax op-eds in local and national newspapers and met with hundreds of elected officials, particularly members of Congress. CCL holds an annual conference and lobby day in Washington, DC. We encourage you to get involved with this effective and convivial group.

Another impressive organization, Get America Working, advocates climate policy that also cuts unemployment by shifting taxes off labor and onto pollution, particularly climate pollution.

We ourselves (Carbon Tax Center) have held several conferences and briefings engaging thought-leaders, environmental and climate activists, and political figures. The most ambitious, our 2010 Wesleyan Conference, attracted some 500 students, activists and citizens to a three-day event kicked off by scientist James Hansen and writer-activist Bill McKibben.

Since 2012, we’ve participated in a series of meetings in Washington, DC organized by our colleagues in the Pricing Carbon Initiative, to discuss and create a political path to include a substantial and briskly-rising carbon tax in broader tax reform. We’ve also cultivated ongoing relationships with environmental justice groups including the trailblazing EJ organization WEACT for Environmental Justice, based in West Harlem in New York City. EJ leaders know that climate damage is already hitting disadvantaged people hardest, and that effective climate policy can and must directly benefit front-line communities through fair and transparent revenue distribution as well as mitigating and avoiding the worst effects of global warming.

As well, CTC has built a network of contacts, supporters and allies within the mainstream environmental movement. Friends of the Earth has demonstrated particular leadership by championing the use of tax policy to advance environmental goals. Taxpayers for Common Sense is another ally in the effort to eliminate costly and wasteful energy subsidies and replace them with taxes on dirty energy. Note also, that thanks in part to the efforts of Progressive Democrats of America, the House Progressive Budget includes a substantial carbon tax as a source of revenue to balance the budget without austerity cuts in social programs and benefits.

For more information, see our Supporters pages.

The Pope’s call for “transparent” internalization of the costs of pollution aligns with mainstream economics’ tenet that a simple, direct carbon tax is the most transparent and effective corrective to shift “the economic and social costs” of climate pollution onto “those who [impose] them” and to broadly incentivize the transition to clean energy and efficiency. For more details, see our post:

The Pope’s call for “transparent” internalization of the costs of pollution aligns with mainstream economics’ tenet that a simple, direct carbon tax is the most transparent and effective corrective to shift “the economic and social costs” of climate pollution onto “those who [impose] them” and to broadly incentivize the transition to clean energy and efficiency. For more details, see our post:

Senator Sanders introduced his

Senator Sanders introduced his  On the Paris climate agreement: “While this is a step forward it goes nowhere near far enough. The planet is in crisis. We need bold action in the very near future and this does not provide that,”

On the Paris climate agreement: “While this is a step forward it goes nowhere near far enough. The planet is in crisis. We need bold action in the very near future and this does not provide that,”  We agree with pioneering climate-scientist

We agree with pioneering climate-scientist

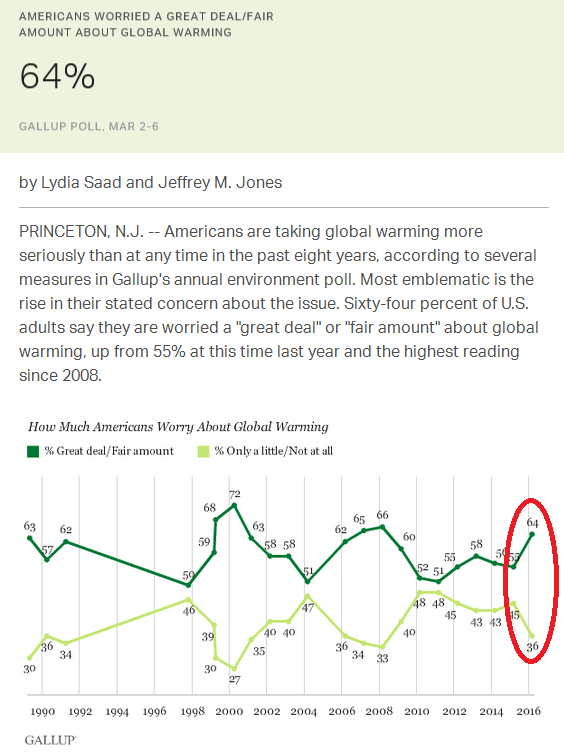

Other results from the 2016 Gallup poll are equally striking. They show a record-high share of Americans stating that climate change poses a threat to them and their way of life; a record number agreeing that climate change is caused primarily by human activity; and climate concern climbing across the political spectrum.

Other results from the 2016 Gallup poll are equally striking. They show a record-high share of Americans stating that climate change poses a threat to them and their way of life; a record number agreeing that climate change is caused primarily by human activity; and climate concern climbing across the political spectrum.