British Columbia Will Keep Raising CO2 Tax If Neighbors Do (Toronto Metro)

Search Results for: introduction

Carbon price working? Coal slumps, clean energy soars

Australia Carbon Tax Already Cutting CO2 (The Age)

Canadians are ready for a carbon tax. Is anyone listening?

Poll: Canadians Support British Columbia-Style Carbon Tax (Globe & Mail)

Arising from the Senate’s Ashes?

And now, ve may begin?

Readers of a certain age, and a certain literary bent, will recognize the words of Alexander Portnoy’s psychiatrist, spoken at the close of Philip Roth’s transgressive 1969 novel, Portnoy’s Complaint.

After lo these many years, they popped into my head today as I read that Senate Democrats had finally thrown in the towel on an energy bill that would have included a partial cap-and-trade provision for limiting carbon emissions from power plants. The bill, written by Senators John Kerry and Joe Lieberman, was touted by Washington insiders and some major environmental groups as this year’s last hope for federal climate legislation. Yet it would have relied on carbon offsets and other dodges to postpone the day of reckoning with true, visible carbon emissions pricing — the cornerstone of meaningful climate policy.

Instead, reported the New York Times, Senate Democrats will pursue a limited bill aimed at increasing oversight of oil drilling and tightening energy efficiency standards — with no direct assault on climate-destabilizing CO2. (For a later Times story amplifying the first, click here.)

Yes, now, we may begin — “we” being Americans who care about climate, sustainability, and Earth — to unite around a climate approach that is effective, equitable and transparent enough to win the support of our fellow citizens and a Congressional majority.

Yes, now, we may begin — “we” being Americans who care about climate, sustainability, and Earth — to unite around a climate approach that is effective, equitable and transparent enough to win the support of our fellow citizens and a Congressional majority.

I’m referring of course to the idea advanced by climatologist Jim Hansen as fee-and-dividend and by the Carbon Tax Center as a revenue-neutral carbon tax, by which fossil fuel extractors and importers pay the U.S. Treasury fees pegged to the carbon content of the coal, oil and gas they take from the ground or bring into U.S. ports, and the Treasury distributes the revenues to all Americans via equal monthly dividends (“green checks”), or by tax-shifting from regressive taxes such as payroll taxes.

The Senate’s antipathy to even the partial cap-and-trade proposed by Sen. Kerry will doubtless be spun as indicating that for the foreseeable future the well for climate legislation has been poisoned. The Carbon Tax Center says that the opposite may be true: with cap-and-trade out of the way at last, the political well can begin to be de-toxified so that the effective, equitable and transparent carbon fee-and-dividend can be seriously considered.

For this to happen, however, the Big Green groups like EDF and NRDC that for years have dominated climate discourse among environmentalists, and that convinced Congressional Democrats and the White House that the only way to “put a price on carbon” in America was via carbon cap-and-trade, will have to abandon that approach and allow others, and themselves, to try a fresh start.

It will be said that cap-and-trade failed because Fox News and other climate deniers branded it as “cap-and-tax” and, therefore, a carbon tax (or fee) cannot possibly succeed. And it is true that carbon cap-and-trade was looked to, years ago, as a way to build on the success of acid rain cap-and-trade, win over Republican free-marketers, and put a price on carbon without having to parade the dreaded t-a-x word before the public.

In the event, though, carbon cap-and-trade did none of these things.

Instead, Big Green’s pursuit of carbon cap-and-trade tethered the climate movement to complex financial instruments and branded us as servants of Wall Street elites. It opened the legislative floodgates to off-the-charts Beltway deal-making that rightly repulsed the public. Perhaps most importantly, the co-optation of climate advocacy by the cap-and-traders robbed us of the high moral ground we might have shared with abolitionists, suffragists, labor agitators and civil rights workers — true American heroes who fought to liberate our society of oppression and injustice.

If you’re in the climate movement, you recognize that fossil fuels’ assault on Earth’s climate is an ultimate form of oppression and injustice: of rich against poor, of the profligate against the frugal, of the present against the future. Ending this assault will require concerted action on many fronts; and it starts by internalizing the climate-damage costs of coal, oil and gas into their prices, so that the free ride for fossil fuels is ended and all of the alternatives, from energy efficiency, renewable energy and low-carbon fuels to conservation-based behavior and mindfulness toward energy consumption, may compete fairly and effectively.

Political action to accomplish this must be done in bright sunlight, not in Beltway shadows.

Cap-and-trade, let us hope, is dead. And now, we may begin!

Photo: Flickr / generica.

The Three Newest Flaws in Cap-and-Trade

Democratic Senators Barbara Boxer (CA) and John Kerry (MA) are expected to introduce their long-awaited climate-change bill tomorrow. As the Houston Chronicle reported last weekend, the bill was delayed for months “by negotiations aimed at appeasing moderate Democrats worried that new emissions caps could impose hefty economic costs on the energy industry, struggling manufacturers and coal mining.”

The Boxer-Kerry bill is expected to be modeled after the Waxman-Markey bill that squeaked through the House in June. This means it will employ the cap-and-trade architecture that underpinned the 1997 Kyoto Accords and has been the cornerstone of the U.S. Big Green lobby’s legislative offensive on climate ever since.

[Addendum: The 821-page Boxer-Kerry “Clean Energy Jobs and American Power Act” was introduced Sept. 30. Go here for text, or here for section-by-section summary. — C.K., Oct. 1.]

Cap-and-trade has been attacked on many grounds: lack of a clear price signal, inherent complexity, and necessary reliance on trading mechanisms that would unleash a pandora’s box of financial machinations that could destabilize global finance. Of late, three new objections have surfaced against cap-and-trade as an “architecture” for reducing greenhouse gases. Each is worth considering as the Senate begins tackling climate legislation in earnest.

Outside NRDC's New York City headquarters, Sept. 24

The first concerns what has heretofore been billed as cap-and-trade’s greatest virtue: its foundation on a quantified emission target, i.e., a “cap.” Alas, the nature of a cap is to be fixed, and therefore not adaptable to changing circumstances — including, now, the sudden drop in U.S. emissions.

As everyone knows, the Great Recession has shrunk economic activity in the United States. And fossil fuel burning and CO2 emissions have been shrinking particularly fast. Consider just one sector, albeit a key one: coal-fired electric power generation.

Until very recently, coal-fired power plants were responsible for almost a third of all U.S. emissions of carbon dioxide. This year, however, the bottom has fallen out.

First-half 2009 figures released last week by the Energy Information Administration show an almost 13% drop in electricity generation from coal and an attendant 11% drop in the physical tonnage of coal burned to make power vis-à-vis the first half of 2008, as coal has absorbed the entire unprecedented 5% drop in overall electricity production. By my calculations, this six-month drop in coal burning alone has already translated to 106 million fewer metric tons of carbon dioxide, singlehandedly reducing total annual U.S. emissions by almost 2%. If continued through December, the 2009 decline in coal burning would cut U.S. emissions by 3% from 2005 levels, thereby achieving, in one sector, almost a fifth of the Waxman-Markey target of reducing 2020 emissions by 17%,

Yes, emissions will eventually “rebound” as economic recovery takes hold. But not all of the lost output will be made up. Moreover, some observers, The Earth Policy Institute’s Lester Brown among them, believe that much of the sudden drop in coal-fired and other emissions is due to emerging structural factors such as fuel-efficiency standards, the liftoff in renewable energy, and more widespread awareness of the perils of oil dependence. These developments too are cutting the Waxman-Markey 17% target down to size. While in theory this “stature gap” could be restored by writing a tougher target into the Senate bill, in practice it’s unlikely the bar will be raised this fall, or ever. If so, the vaunted “emissions certainty” in cap-and-trade will lock in a hollow achievement.

The second new flaw, variously referred to as the “voluntary reductions conundrum” or the “virtue dilemma,” concerns the prospect that under a cap-and-trade regime, any “extra” steps to reduce CO2 emissions stand to be canceled out by corresponding increases in emissions that the cap enables somewhere else. In effect, any action to, say, ride a bike instead of driving (or, on a larger scale, to create a bicycling infrastructure that can replace thousands of car trips), or to permit a wind-turbine farm whose output allows the grid to cut back on fossil-fuel generation, ends up creating “room” under the cap that lets other parties increase driving or coal-burning and emit the “saved” emissions.

The mechanism for this perverse consequence of a carbon cap would be a decrement in the auction price of allowances due to the increment in bicycling or wind output, encouraging a corresponding increment in driving or fossil-fuel power generation elsewhere within the capped entity. In effect, the celebrated cap in cap-and-trade dictates an emissions equilibrium that, in turn, vitiates any given decarbonizing measure which, absent the cap, would have reduced emissions.

The implication is troubling, to say the least. No more could one promote a proposed renewable-energy or energy-efficiency project as a climate-saver, if its fossil-fuel-saving virtue will be offset by an equal helping of fossil-fuel vice somewhere else. At the same time, a dirty-energy project (or failure to implement a clean one) could be justified on the grounds that the resulting propping up of allowance prices will enable other low-carbon investments or behaviors to come into being and pick up the slack. The idea that “the cap will provide” turns out, it seems, to be a two-edged sword.

The third and last cap-and-trade flaw attracting notice concerns transnational fungibility. Shorn of its recondite name, it denotes the difficulty if not impossibility of establishing a normative quantity-reduction target for greenhouse gases. In a nutshell, if the U.S. were to establish an emissions reduction goal of 17%, or any other number, for 2020 or any other future year, by what criterion should that target be deemed appropriate for any other country? After all, the United States emits twice as much CO2 per capita as comparably wealthy countries in Europe, and, of course, 5 to 20 times as much per person as China, India, Brazil, et al. (And this comparison doesn’t reflect the even greater disparities in historical or aggregate emissions.)

Needless to say, this problem of fungibility, or its lack, doesn’t apply to a carbon tax. A U.S. carbon tax of so many dollars per ton of CO2 might or might not be the “optimal” level, but it would at least translate fairly and equally across borders, disadvantaging manufacturers in every nation more or less equally. Moreover, as Elaine Kamarck has pointed out, many countries lack the administrative capacity to manage a cap-and-trade system, whereas most governments can at least collect taxes.

Nor would a carbon tax be beset by flaws #1 or #2. The impacts of a carbon tax on U.S. investment decisions, infrastructure provisions and personal behaviors will be relatively unaffected by aggregate contractions in emissions. Moreover, unlike cap-and-trade, a carbon tax won’t undercut virtue but will reinforce it, since each and every elimination of emissions will be rewarded by a corresponding reduction in the tax.

At this point, cap-and-trade seems to have little going for it other than institutional inertia. Let us hope that all of its drawbacks are closely and fairly scrutinized in the Senate debate now set to begin.

Photo: David Pine, rising tide north america

What Can Replace Faltering Cap-and-Trade?

Is Waxman-Markey doomed? Revulsion at the special favors and sheer complexity built into the 1,400-page bill that squeaked through the House in June has been building nationwide this summer. Now, a Washington Post editorial signals the impending collapse of not just the bill but of cap-and-trade as the central mechanism for controlling U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

The Post wrote earlier this week:

The rancorous debate over health reform has given voice to considerable uneasiness among Americans. Many are worried about how a new system will be paid for in an economy that has unraveled, and they are anxious about a kudzu-like expansion of an already unwieldy bureaucracy. Given the herculean effort it will take to get President Obama’s vision of reform through Congress, we’re not convinced that the Senate will have the stomach to tackle cap-and-trade legislation this fall. The growing agitation within the chamber over the creation of another complex system to buy, sell and trade pollution credits only adds to our doubts. (emphasis added)

As the Post editorial noted:

The House barely passed the American Clean Energy and Security Act (a.k.a. Waxman-Markey) in June. The 1,400-page bill has a potpourri of measures ranging from new efficiency and renewable energy standards to a cap-and-trade provision that gives away 85 percent of the pollution allowances to various interests. The Senate is proving to be a much tougher sell. Last week, four Democratic senators — Blanche Lincoln (Ark.), Ben Nelson (Neb.), Kent Conrad (N.D.) and Byron L. Dorgan (N.D.) — called on the leadership to strip cap-and-trade completely from the bill that Majority Leader Harry M. Reid (D-Nev.) hopes to start stitching together next month. This comes days after 10 moderate Democratic senators from coal and manufacturing states sent a letter to President Obama warning that they would not go along with any cap-and-trade regime that didn’t “maintain a level playing field for American manufacturing.” (emphasis added)

The fact that the epicenter of discontent is the coal-dependent “heartland” region indicates that Waxman-Markey has been more heavily attacked from the Right than the Left — as the Post itself signaled through its editorial title “Cap and Rage” and subtitle, “The fight over health-care reform could hobble climate-change legislation.” As we see it, the Big Green groups that steered Congress onto the cap-and-trade path and also failed to insist on 100% permit auctioning and at least near-revenue neutrality share blame for the virulent attacks. Their stance helped turned the House bill into a perfect target for caricature as a “cap-and-tax” bill or “cap-and-trade tax” that would push hard-pressed American families, businesses and industries over the financial edge.

Nevertheless, the Post reports that:

Dropping cap-and-trade from the Senate bill is considered a non-starter by Mr. Reid and environmental advocates for two reasons. First, a long-stated goal of congressional leaders and the president himself is to have emissions-limiting legislation passed and signed into law in time for international climate talks in Copenhagen in December. Second, there is no Plan B. The leadership has put all of its eggs in the cap-and-trade basket.

Fortunately, the Post hastened to remind Majority Leader Reid that there is indeed a Plan B:

Yet there are other options worthy of consideration. Yes, we’re talking about a carbon tax. It would be relatively simple to devise and easy to implement. It would require no new bureaucracy, and the revenue generated could be rebated to the taxpayer in any number of ways — through a payroll tax reduction, for instance. (emphasis added)

The Post editorial acknowledged:

We know we are running counter to Washington’s tax-averse conventional wisdom. But we are not alone in our support of the carbon tax. There were three such bills in the House [including the Larson bill, which is more than 95% revenue-neutral and, with an upward-adjustable tax rate, is the most “cap-like” but without the politically toxic “trade” aspect]. One of the inventors of the cap-and-trade concept, Thomas Crocker, told the Wall Street Journal last week that he favors a carbon tax because he believes it’s easier to enforce.

The editorial concluded:

If Congress fails to pass cap-and-trade legislation, it will rapidly approach a fork in the road in addressing global warming. Members can sit back while unelected bureaucrats at the Environmental Protection Agency follow through on their moves toward regulating greenhouse gas emissions as a pollutant under the Clean Air Act. Or they can entertain a carbon-based tax designed to reduce emissions and give the money back to taxpayers in an equitable manner. A decision on which path to take is bearing down upon us. Not only are the global warming dangers facing the planet reaching the tipping point, but there will also be no climate agreement in Copenhagen without strong leadership in words and deeds from the United States. As the Senate forges ahead, nothing should be off the table.

We agree, of course, that nothing should be off the table. The demise of Waxman-Markey won’t be pretty, but it should spur all who grasp the criticality of the climate crisis to unite behind the quickest, fairest and most effective means to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions: a national, revenue-neutral carbon tax.

Photo: Flickr / afagen.

Does Cap-and-trade Punish Virtue?

Another question directed to the Carbon Tax Center: Would a carbon emissions cap become an emissions minimum as well as maximum, in effect precluding reductions below the cap level?

A “cap” of the type embedded in the House-passed Waxman-Markey bill (ACESA) is a legislated number of allowances, or permits, corresponding to tons of CO2 to be emitted. If the number of allowances is less than total expected CO2 emissions for that year, the shortfall will create an allowance price sufficient to drive demand down to the cap level. A too-loose cap (where allowances exceed emissions) will cause the carbon permit price to approach zero, as has occurred in the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme.

Now, what happens if some people “virtuously” reduce emissions for altruistic reasons? Would they simply be making room under the cap for more emissions by someone else? Prof. James Kahn at Washington & Lee University examined a similar issue: the ramifications of hypothetical new low-carbon energy technology under a cap. Using standard tools of economic analysis such as demand curves, Kahn found that the reduction in allowance prices due to the new technology would stimulate new demand that would exactly cancel out the reduction in emissions. Extrapolating from Kahn, it appears reasonable to expect that altruistic reductions under a carbon cap would similarly reduce allowance prices and create a price signal to consume more, thus canceling out those reductions.

This perverse consequence of a carbon cap makes perfect sense, unfortunately. Consider a commuter who, independent of any price signal or federal legislation, resolves to give up solo car commuting for a carpool. Under a cap system, this “exogenous” reduction in demand for carbon emitting will lead to a slightly lower emission permit price — thus stimulating some additional use of fossil fuels elsewhere. The incremental usage might be a reciprocal departure from a carpool, or cranking up the heat, or a return to buying bottled water rather than refilling at the tap … or any of a thousand other ways to burn carbon. The result, in the end, will be the same: virtue in one arena will be offset elsewhere, due to the price-equilibrium-seeking mechanism of the cap.

This perverse consequence of a carbon cap makes perfect sense, unfortunately. Consider a commuter who, independent of any price signal or federal legislation, resolves to give up solo car commuting for a carpool. Under a cap system, this “exogenous” reduction in demand for carbon emitting will lead to a slightly lower emission permit price — thus stimulating some additional use of fossil fuels elsewhere. The incremental usage might be a reciprocal departure from a carpool, or cranking up the heat, or a return to buying bottled water rather than refilling at the tap … or any of a thousand other ways to burn carbon. The result, in the end, will be the same: virtue in one arena will be offset elsewhere, due to the price-equilibrium-seeking mechanism of the cap.

It gets worse: ACESA includes both a cap and a “renewable electricity standard” (RES) which mandates that electric utilities buy a gradually-increasing fraction of their energy from renewable sources. Resources for the Future studied this same policy combination in Germany. Its finding: Germany’s combination of an RES with a cap caused an increase in the use of coal to generate electricity, as the growth in renewable-energy output created room under the cap for more coal-fired generation elsewhere. In effect, the renewables displaced natural gas-generated electricity instead of coal because gas was more costly, even with coal’s much (roughly 80%) higher carbon content and allowance cost. (This perverse incentive would disappear if allowance prices rose to a level making electricity generation from coal more costly than natural gas.)

To summarize, a carbon cap would tend to cancel out emissions reductions resulting from personal choices and from new technologies. Virtuous conservation and new technologies would reduce allowance prices, stimulating more consumption by others. And, by combining renewable electricity standards with a cap, ACESA would create another perverse incentive because shifting electricity generation to renewables tends to make more room under a cap for coal emissions.

A carbon tax, in contrast, would be free of such “canceling out” mechanisms. Indeed, if anything, “my” tax-induced conservation would tend to encourage “yours” by helping move societal norms away from consumption. And a gradually increasing carbon tax would obviate the need for renewable electricity standards by increasing the cost of high-carbon fuels and stimulating demand for low-carbon alternatives.

Finally, a carbon tax would sidestep what is likely to be cap-and-trade’s biggest “toxic” side effect: a volatile new carbon market that would benefit only speculators and could crash world financial markets again.

Photo: Flickr / megabooboo.

New Larson Bill Raises the Bar for Congressional Climate Action

Carbon taxing to safeguard Earth’s climate took several major steps forward — politically and intellectually — with the introduction yesterday of the America’s Energy Security Trust Fund Act of 2009 by Rep. John B. Larson, chair of the House Democratic Caucus and fourth-ranking Democrat in the House of Representatives.

The new bill builds and improves on Rep. Larson’s 2007 bill with these provisions:

- The first-year tax rate is $15 per ton of carbon dioxide.

- The rate rises by $10/ton per year.

- After five years, that increase rate is automatically bumped up to $15/ton if U.S. emissions stray from an EPA-certified glide path to cut emissions by 80% from 2005 levels in 2050.

- To protect domestic manufacturers, the bill authorizes the Treasury Department to impose a “carbon equivalency fee” on carbon-intensive products imported from non-carbon-taxing nations.

- Clean-tech R&D and investments are eligible for $10 billion a year in tax credits.

- Impacted workers and industries are eligible for transition assistance of $7.5 billion in the first year; this is phased out after year 10 but still totals $41 billion.

- All other revenue is tax-shifted to Americans via reductions in payroll taxes.

Rep. Larson, a member of the powerful, tax-writing Ways & Means Committee, appears to have crafted his new bill to counter most if not all salient objections to carbon taxing:

-

To the insistence on emission guarantees: the Larson bill responds to the “quantity-certainty” objection by virtually guaranteeing deep emission cuts. Emissions would fall to 25% below 2005 levels in 2022, according to CTC’s conservative carbon tax-impact model. If that’s insufficient, the automatic tilt to a $15 annual increment will push the 2022 reduction percentage higher (we estimate to 30%), with cuts continuing after. The average annual decline rate in that scenario matches the 2% target rate in most cap-and-trade proposals and kicks in much more quickly, due to the tax’s shorter lead time.

- To concerns about “tax-and-spend”: over the first ten years, 96% of revenues would be returned to U.S. families. The recapture percentage reaches 99% in year 15.

- To fears of eroding U.S. competitiveness: the payroll-tax reductions provide the much-sought “double dividend” of stimulating the economy while encouraging work. The carbon equivalency fees protect against lagging nations stealing market share from U.S. manufacturers.

- To calls for clean-tech R&D and investment: in tandem with the tens of billions in tax credits and other incentives for efficient and renewable energy in the new American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the $10 billion annual allocation will support critical research, demonstration and deployment of energy efficiency and renewables.

- To those in impacted industries and regions: the $41 billion in grants will likewise help workers and communities make the transition to low-carbon and zero-carbon industries.

The Larson bill isn’t perfect; for one thing, the energy-price protections from the payroll tax-shift will need to be extended to non-working families and individuals. But the automatic upward adjustment in the carbon tax rate, if required to meet certified emission goals, is a big step forward, and should help allay concerns of cap-and-trade adherents over any quantity-uncertainty with a carbon tax.

Equally impressive is the Larson bill’s carbon tax level; with an increment rate of either $10 or $15 a ton per year — implying annual increases of at least 10 cents per gallon of gasoline and ¾ of a cent per kWh for electricity on a national-average basis — producers, consumers and intermediaries will be moved inexorably to lower-carbon investments and choices.

What may make the robust carbon tax level politically feasible, in turn, is that only a small and declining fraction of the revenue is earmarked for new programs. As noted, by the tenth year, 98% of incoming revenue (96% of cumulative) will be recycled to workers and their families. This should be attractive to growth advocates, deficit hawks and advocates for working families.

Prospective losers: profligate emitters, oil barons and sheiks, mountaintop miners, and ideologues who regard as anathema governmental action to correct “the greatest market failure the world has seen.” And, oh yes, cynics who said the U.S. could never enact a meaningful carbon tax.

Photo: Flickr / himesforcongress.

A Day To Celebrate

Canada Day — the First of July — is observed "not only throughout the nation, but also internationally." This year, Canada’s third-most populous province is giving the world extra cause to celebrate: on July 1, British Columbia becomes the first state or province in the Western Hemisphere with a comprehensive, revenue-neutral carbon tax.

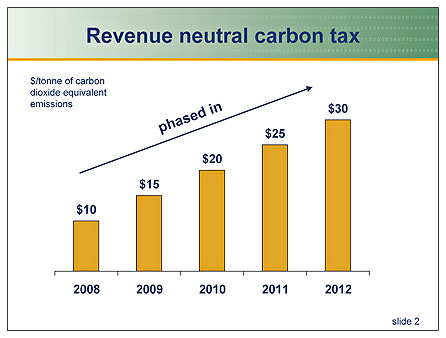

The BC carbon tax starts at a level of $10 (Canadian) per metric ton of carbon dioxide, equivalent to 2.41 (Canadian) cents per litre of gasoline. In U.S. terms and at current exchange rates, that’s $8.91 per short ton, or just under 9 cents per gallon of gas. The rate rises by $5 in each of the next four years, reaching $30 Canadian per tonne (U.S. $26.73 per ton) in 2012.

The tax is revenue-neutral. As we reported in April, the province’s Finance Ministry has dedicated the revenues to four tax reduction measures:

- A new Climate Action Credit will pay lower-income BC’ers $100 per adult and $30 per child per year.

-

The bottom two personal income tax rates have been reduced by 2% on the first $70,000 in earnings.

-

The corporate income tax rate has been reduced to 11% from the current 12%.

-

The small business tax rate has been cut to 3.5% from 4.5%.

Each provision will expand in tandem with the tax rate. And, showing impressive political pitch, the ministry last week preceded the tax with what it calls “an immediate Climate Action Dividend” — $100 for every man, woman and child in British Columbia — via dividend checks sent to province residents.

The BC program has catalyzed an intensive discussion of carbon taxes across Canada. Liberal Party Leader Stéphane

Dion is staking his party’s campaign to replace the Conservative government on a carbon tax featuring a $15.4 billion, four-year Green Shift. Canadians are receiving, and participating in, a national tutorial on carbon pricing, “tax vs. cap” and revenue-neutrality.

The BC tax is modest. One

source says it will deliver less than a tenth of the province’s legislated greenhouse gas reductions for 2020. That’s partly because abundant hydropower has obviated the need for fossil fuels to generate electricity. (Memo to BC: please consider an excise tax on electricity; power surpluses from price-induced conservation could be sold into the grid, with revenues flowing to the Climate Action Dividend.)

Still, the tax is a giant step — even a leap. At midnight tonight, North America will have its first large-scale, socially-mandated carbon price. Millions of carbon-impacting decisions will begin to be made with at least some recognition of the climate-curing effect of reduced carbon emissions.

Starting now, BC residents who use less carbon than average will be rewarded with an income boost. With luck, the province’s ruling Liberal Party will be rewarded as well by voters for showing courage, vision and populist appeal. And perhaps in the not too distant future the U.S. will take a page from its northern neighbor’s play book and supplement its imports of ice-hockey players and Canadian Club with something even more sustaining.

Graph: Flickr/paradigm4.

Boxer the Trapper (of Global Warming Deniers)

Guest Post by James Handley

I’m a bit surprised that Republicans fell into Boxer’s trap so predictably. With a slim Democratic majority in the Senate and a promised presidential veto, the Lieberman-Warner (“Climate Security”) bill never had a chance. Senate Environment and Public Works Committee Chair Barbara Boxer forced a vote so the environmental score-keepers could notch one up for the Ds and one down for the Rs.

The bill was deeply flawed — Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace and a coalition of other progressive environmental groups point out that it would GIVE AWAY most of the carbon emission permits to polluters. Instead, these groups advocate auctioning ALL permits. Both Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama also support 100% auction. So Lieberman-Warner was already way behind the political curve.

The bill would have auctioned a minority of permits. Who would the lucky revenue winners have been? Mostly big (polluting) energy corporations.

Rep. Markey (D-Mass) introduced a House bill to auction 97% of permits and distribute revenue to individuals, while Sen. Corker (R-Tenn) offered similar amendments in the Senate: worthy improvements that didn’t get serious consideration (yet).

Lieberman-Warner was a trial balloon, but more than that, it was a trap to entice the howling dogs who deny the climate problem out into the open so Democrats and environmental groups can campaign against them. As legislation, it’s a failure. As political strategy, it lured them out and slapped shut with the alacrity of a mouse trap. I can’t help wondering why the Republican leadership didn’t try to improve the bill (or at least fake doing so) instead of obstructing it. There’s plenty to improve on (like moving from cap-and-trade to a carbon tax and requiring revenue-neutrality) and they could have avoided being tarred as Neanderthal global warming deniers.

Boxer’s political trick worked and may provide the Democratic Party with real political benefits as voters register their impatience in November. Unfortunately, the focus on a poorly-designed bill and the failure to consider constructive changes resulted in a wasted opportunity.

Economists from left to right agree that the gold standard for effective climate policy is a revenue-neutral carbon tax with dividend. Maybe the spectacular crash of Lieberman-Warner will help us start that much-needed discussion after the election.