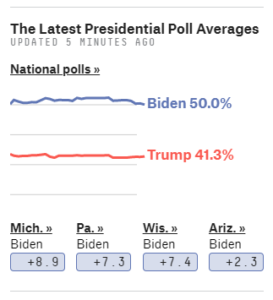

Could a carbon tax emerge from the U.S. elections? Quite possibly.

The apparent results — a narrow Biden win coupled with continued Republican control of the Senate — do not bode well for the Investment and Justice legs of the climate left’s ambitious “S-I-J” triad. Many elements of the third leg, Standards, can be enacted through executive orders (e.g., restoring auto mileage and other efficiency regulations eviscerated by the Trump administration). Not so the Green New Deal components such as large-scale federal investment in renewables, mass transit and sustainable communities.

It could be, however, that a carbon price could qualify as a rare climate measure palatable to enough Republicans to make it into legislation next year.

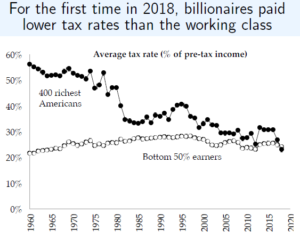

“Divided control of government will likely not yield a wealth tax, progressive taxation or Green New Deal-style policy,” NY-based political strategist Neal Kwatra wrote today, and we agree. Republicans will not bend in protecting extreme wealth. They also disdain a GND, not just on account of its identification with Justice Democrats standard-bearer Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez but because it harkens to an era in which muscular, compassionate government went to bat for the common good. While it doesn’t necessarily follow that Republicans will accede to taxing carbon emissions — the G.O.P.’s climate stance long since ossified into deflection and denial — a carbon tax could become the party’s way to bow to political and demographic reality and finally signal a modicum of climate concern.

As readers of this blog know, it has become increasingly clear to us that, standing alone, a carbon tax has become too fraught politically and too weak economically to serve as the centerpiece of U.S. climate policy. We concluded last year that the path to decarbonizing the U.S. economy lay in Green New Deal-inspired infrastructure and investment funded by taxes on extreme wealth and supported by a carbon tax.

We envisioned a three-part program to accomplish this:

- A Green New Deal plan investing 10 to 20 trillion dollars over a 10-year period to develop the infrastructure, industrial capability, and consumer incentives to quickly decarbonize the U.S. energy system.

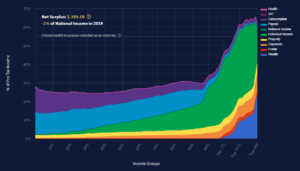

- New taxes on extreme wealth and financial transactions, supplemented by increases in estate taxes, marginal income tax rates, capital gains and corporate taxes, to generate, from the wealthiest American households, the funds needed to pay for the Green New Deal.

- A rising charge on carbon emissions from fossil fuels that would support the Green New Deal by shortening payback periods for green investment and inculcating energy efficiency and conservation throughout American society.

The Democrats’ apparent failure to capture the Senate will almost certainly put #1 and #2 on hold at least till the 2022 midterms — and probably beyond, given the strong tendency of the ruling party to shed Congressional seats in off-year elections. Not only that, divided government will make it much harder for a Biden administration to push through the progressive changes in areas like health care and racial equity that might have created political capital to pass elements of the ambitious program sketched above.

Nevertheless, the relentless rise in jobs in clean energy coupled with the long-term shrinkage in fossil fuel industry employment might reduce the political cost to some G.O.P. senators to act on climate. If so, a carbon tax, especially a revenue-neutral one that sends the carbon revenues to households rather than government, would be somewhat “on brand” with traditional Republicanism — if there is still such a thing.

Needless to say, the persistence of the Republican Senate majority means that the filibuster remains, markedly complicating the legislative path to a federal carbon tax. (Molly Reynolds of the Brookings Institution recently posted an excellent primer on the filibuster with a section devoted to “the budget reconciliation process” which allows a simple majority to adopt certain bills addressing spending and revenue provisions, thereby circumventing the filibuster.)

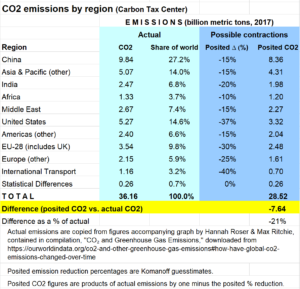

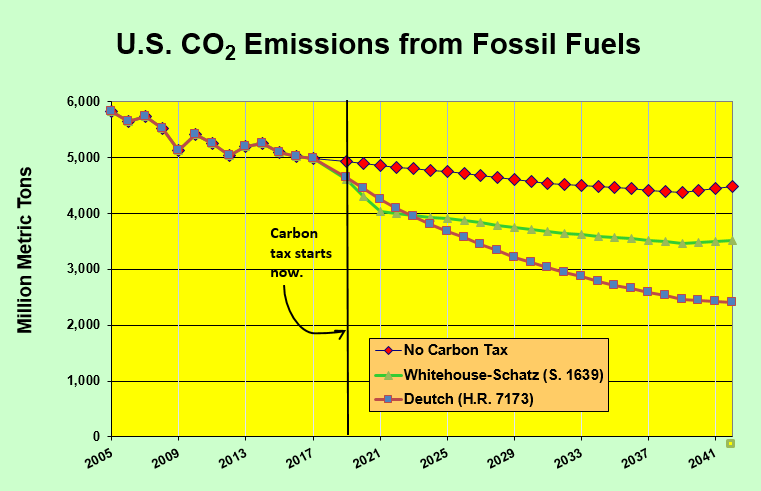

But if events do break in the direction of pricing carbon emissions, climate advocates had better stand tough for a strong carbon tax. Not the $20 per ton of CO2 that Exxon occasionally bandied about during Obama’s presidency. And probably not even the $40/ton tax promoted by the Climate Leadership Council, unless the council can be persuaded to increase its preferred 5% real annual rises which would tack on just a few dollars each year following that initial jolt.

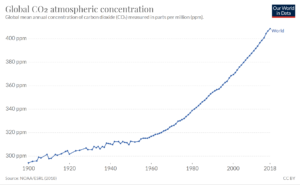

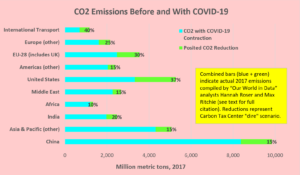

No, a carbon tax worth fighting for has to hit triple digits before long, say, by year six or seven. That’s the trajectory that can drop emissions by a third in a decade and that would be a worthy template for other major emitting countries, allowing the U.S. action to ripple productively around the world.

A carbon tax centering U.S. climate policy is the outcome we sought when we founded CTC at the start of 2007. Nearly fourteen years on (and largely squandered by Republican obstructionism), a carbon tax by itself isn’t enough to stave off climate hell. But it’s still well worth fighting for.