This page features a selection of articles, video clips and books from a variety of perspectives making the case for taxing climate pollution.

Articles

Let this be the year when we put a proper price on carbon

Lawrence Summers, who has served as Treasury Secretary, President of Harvard University and Chief Economist of the World Bank, trenchantly articulated the compelling reasons and auspicious timing for a carbon tax in an op-ed in both the Financial Times and the Washington Post (January 5, 2015). We offer some excerpts:

The case for carbon taxes has long been compelling. With the recent steep fall in oil prices and associated declines in other energy prices it is overwhelming. There is room for debate about the size of the tax and about how the proceeds should be deployed. But there should be no doubt that starting from the current zero tax rate on carbon, increased taxation would be desirable.

[T]hose who use carbon-based fuels or products do not bear all the costs of their actions. When we drive our cars, heat our homes or use fossil fuels in more indirect ways, all of us create these costs without paying for them. It follows that we overuse these fuels. While the recent decline in energy prices is a good thing in that it has, on balance, raised the incomes of Americans, it has also exacerbated the problem of energy overuse. The benefit of imposing carbon taxes is therefore enhanced.

[A] well-designed tax would be levied on the carbon content of all imports coming from countries that did not impose their own carbon levies. The United States can make the case that such a tax is compatible with World Trade Organization rules. Such an approach would have the virtue of encouraging countries who wished to avoid the U.S. tax to impose carbon taxes of their own, thereby further supporting efforts to reduce global climate change.

A U.S. carbon tax would… be a hugely important symbolic step ahead of the global climate summit in Paris late this year. It would shift the debate toward harmonized measures to raise the price of carbon use and away from the complex cap-and-trade-type systems that have proved more difficult to operate than expected in the European Union and elsewhere.

My preference would be for the funds to be split between investments in infrastructure and pro-work tax credits. An additional $50 billion a year in infrastructure spending would be a significant contribution to closing America’s investment gap in that area. The same sum devoted to pro-work tax credits could finance a huge increase in the earned-income tax credit, a meaningful reduction in the payroll tax or some combination of the two.

Progressives who are most concerned about climate change should rally to a carbon tax. Conservatives who believe in the power of markets should favor carbon taxes on market principles. And Americans who want to see their country lead on the energy and climate issues that are crucial to the world this century should want to be in the vanguard on carbon taxes. Now is the time.

Bigger, Cleaner, and More Efficient: A Carbon-Corporate Tax Swap

Donald Marron served as economic adviser to President G.W. Bush, acting director of the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office and executive director of the Joint Committee on Taxation. Marron now co-directs the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. In a 2013 paper, he and Eric Toder analyzed the climate and macro-economic benefits of a carbon tax “shift” to reduce top corporate income tax rates. In the Cato Online Forum (November 2014) Marron outlined the conservative principles behind his proposal to combine effective climate policy with pro-growth economic policy:

Four recurring lessons from tax and environmental policy…

First, taxing bads is better than taxing goods. When the government levies a tax, people and businesses are less likely to do the taxed activity…

Second, putting a price on carbon is the most efficient way to reduce carbon emissions. In the absence of a national carbon price, as from a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade system, policymakers will likely continue to pursue piecemeal regulations and subsidies. Indeed, we see that today in heightened fuel economy standards and state-by-state electric power plant regulations. These regulatory efforts can reduce emissions, but at greater cost per ton than a national carbon price.

Third, the corporate income tax is especially distortionary… it discourages business investment and weakens economic growth… [T]he Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development identified corporate income taxes as having “a particularly negative impact on GDP per capita,” especially through their effect on “dynamic and innovative” businesses.

Fourth, America’s corporate income tax is especially problematic. The statutory tax rate is the highest in the world at more than 39 percent (including federal and state taxes) and the U.S. is one of only a few nations that taxes resident corporations on their worldwide income. At the same time, our corporate system includes many tax breaks that dramatically lower the effective rate some businesses really pay. This toxic mix benefits lawyers and accountants but has made the United States an unattractive place for many firms to maintain their legal residence. One symptom has been the recent increase in tax-driven inversions.

[A] carbon-corporate tax swap, paired with appropriate relief for low-income families, would make our economy bigger, cleaner, and more efficient.

A Carbon Tax Is Our Only Hope

In the edgy “Gawker” magazine (May 27, 2014), Hamilton Nolan trenchantly explained why, if we’re serious about tackling global warming, we need a stiff carbon tax to climate polluters:

Why does a pack of cigarettes cost fifteen… dollars in New York City? Because New York City uses taxes to add the future costs of smoking to the cost of smoking today. We know that smokers end up costing society a lot of money for health care years down the road; with cigarette taxes, smokers in the city pay those costs up front. The realization of the true cost of a negative behavior is quite an effective way to not only pay those costs, but also to change the behavior.

This is the basic rationale for a carbon tax. We know that carbon emissions are causing global warming, which will impose a disastrous cost on all of humanity in the years to come. So make those who emit carbon pay those costs up front, by taxing them…

There is no other tactic that will have as big an impact on carbon emissions within our 15-year window of opportunity for action. Forces that operate solely out of self interest will continue to oppose any and all sacrifices right up until the sea swallows their vacation homes. Forget them. The activists and political leaders who have genuine concern about this issue must all unite around some form of carbon tax as a solution. Fighting polluters on a piecemeal basis will not be enough. Public education campaigns will not be enough. Global warming must be made too expensive to be viable. Tax the hell out of it. It’s not unfair pricing. On the contrary, it is the only way to make carbon emissions exactly as expensive as they deserve to.

Science Is Unequivocal, Policy Is Obvious: Tax CO2 Pollution

New Yorker science writer and author of “Field Notes From a Catastrophe,” Elizabeth Kolbert linked the overwhelming climate science consensus to ith the equally robust climate economics consensus (April 14, 2014):

[T]he Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released its latest update on the looming crisis that is global warming. Only this time it isn’t just looming. The signs are that “both coral reef and Arctic systems are already experiencing irreversible regime shifts,” the panel noted… The I.P.C.C.’s list of potential warming-induced disasters—from ecological collapse to famine, flooding, and pestilence—reads like a riff on the ten plagues. Matching the terror is the collective shame of it. “Why should the world pay attention to this report?” the chairman of the I.P.C.C., Rajendra Pachauri, asked the day the update was released. Because “nobody on this planet is going to be untouched by the impacts of climate change.”

Economists on both sides of the political spectrum agree that the most efficient way to reduce emissions is to impose a carbon tax. “If you want less of something, every economist will tell you to do the same thing: make it more expensive,” former Mayor Michael Bloomberg observed, in a speech announcing his support for such a tax. In the United States, a carbon tax could replace other levies—for example, the payroll tax—or, alternatively, the money could be used to reduce the deficit. Within a decade, according to a recent study by the Congressional Budget Office, a relatively modest tax of twenty-five dollars per metric ton of carbon would reduce affected emissions by about ten per cent, while increasing federal revenues by a trillion dollars. If other countries failed to follow suit, the U.S. could, in effect, extend its own tax by levying it on goods imported from those countries.

All You Need to Know About British Columbia’s Carbon Tax Shift in Five Charts

Alan Durning and Yoram Bauman, of the Seattle-based Sightline Institute, graphically illustrated the economic and climate success of their northern neighbor British Columbia’s simple, revenue-neutral carbon tax (March 11, 2014):

BC’s carbon pricing system is the best in North America and probably the world. The province has finished the nitty-gritty work of drafting statutes and regulations to implement the system. Oregon and Washington could do worse than to copy them, word for word, into their tax codes, then make adjustments needed to match circumstances.

Economists Have A One-Page Solution to Climate Change

National Public Radio reporter David Kestenbaum neatly distilled why economists are virtually unanimous in concluding that well-designed carbon taxes offer a win-win for the climate and the economy that no other policy can beat (June 28, 2013):

This is why economists love a carbon tax: One change to the tax code and the entire economy shifts to reduce carbon emissions. No complicated regulations. No rules for what kind of gas mileage cars have to get or what specific fraction of electricity has to come from wind or solar or renewables. That’s by and large the way we do it now.

[MIT economist John] Reilly says the current web of rules is a more complicated and more expensive way of getting the same outcome as a carbon tax. The current system “pretty much is one of the worst ways we could do it,” he says.

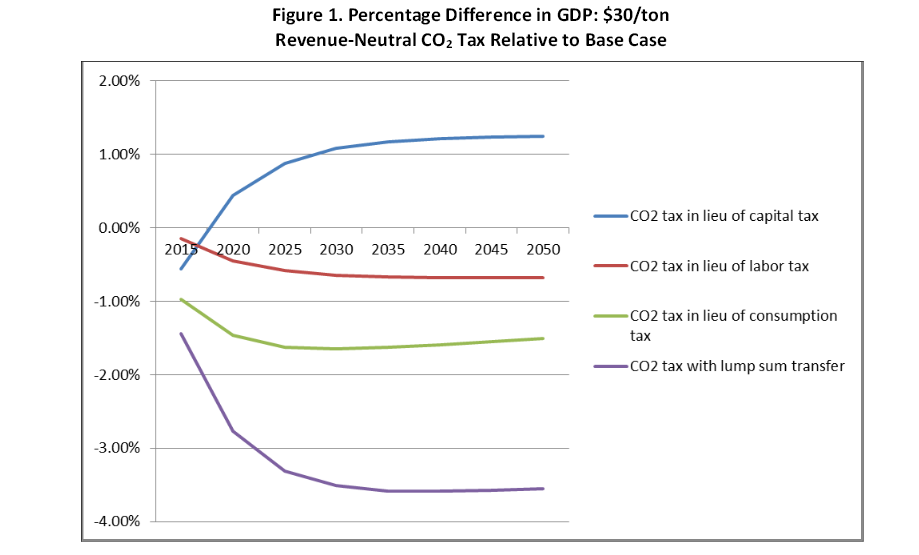

… Reilly brings up what is perhaps the most surprising thing about a carbon tax: If you do it right, he says, carbon tax can be nearly painless for the economy as a whole.

Besides reducing carbon emissions, a carbon tax brings in a bunch of money — it’s a tax after all. So, Reilly says, you can reduce, say, income tax to balance out the new taxes people are paying for carbon emissions. People pay more for gas, but they get to keep more of their income.

Laura D’Andrea Tyson: The Myriad Benefits of a Carbon Tax

A Bill Clinton Council of Economic Advisers chair urged carbon taxes as more cost- and climate-effective than regulations and subsidies (New York Times, June 28, 2013)

Without a [carbon] tax, the government has to rely on second-best regulations to limit carbon emissions. Facing Congressional inaction and staunch opposition to a carbon tax, this week President Obama proposed regulations on carbon pollution standards for new and existing power plants using his executive authority under the Clean Air Act.

A carbon tax is also a cheaper and often more efficient way to reduce carbon emissions than subsidies for alternative fuels. Generous subsidies for biofuels have cost billions of dollars; by reducing the price of gasoline they may have perversely increased rather than decreased carbon emissions.

Other subsidies, like the production tax credit, have been successful at ramping up research, development and deployment of alternative energy technologies in recent years. Such subsidies would be even more effective in combination with a carbon tax that would make fossil fuels less price-competitive and would stimulate research on renewable and energy-saving technologies.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that even a modest carbon tax could reduce both greenhouse emissions and the federal budget deficit. A tax of $20 per ton of carbon dioxide, which would translate to about 15 cents per gallon of gasoline, would reduce emissions by 8 percent and generate up to $1.2 trillion in tax revenues over 10 years.

“[A] Carbon tax…would make polluters pay for their own pollution”

As EPA began rolling out its proposed regulations on power plants, the Washington Post Editorial Board suggested a better way (May 7, 2013):

[A] carbon tax, an elegant policy Congress could immediately take off the shelf… would make polluters pay for their own pollution, which is the best way to encourage greener thinking. It would cut emissions without overspending national wealth on grandiose central planning or command-and-control regulation. And it would raise revenue, which lawmakers could use for debt reduction, lowering other taxes, improving the social safety net or some combination. The carbon tax is one of the best ideas in Washington almost no one in Congress will talk about.

Conservative icons George Schultz and Gary Becker on why they support a Carbon Tax

Nobel-winning economist Gary Becker and Reagan-Nixon cabinet secretary George Shultz proposed to replace costly clean energy subsidies with a far more effective revenue-neutral carbon tax. (Wall St. Journal, April 7, 2013):

[W]e should seek out the many forms of subsidy that run through the entire energy enterprise and eliminate them. In their place we propose a measure that could go a long way toward leveling the playing field: a revenue-neutral tax on carbon, a major pollutant. A carbon tax would encourage producers and consumers to shift toward energy sources that emit less carbon—such as toward gas-fired power plants and away from coal-fired plants—and generate greater demand for electric and flex-fuel cars and lesser demand for conventional gasoline-powered cars.

We argue for revenue neutrality on the grounds that this tax should be exclusively for the purpose of leveling the playing field, not for financing some other government programs or for expanding the government sector. And revenue neutrality means that it will not have fiscal drag on economic growth.

The Market and Mother Nature

Economist and columnist Thomas Friedman urged climate hawks and deficit hawks to find common cause in support of a deficit-reducing carbon tax. (New York Times, January 8, 2013):

I am struck by how many liberals insist on reducing carbon emissions immediately, but, on the deficit, say there is no urgency because no interest rates rises are in sight. And I am struck by how many conservatives insist we must reduce the deficit immediately, but, on climate, say there is no urgency because, so far, temperature rise has been slight… A carbon tax would reinforce and make both strategies easier.

In Defense of a Carbon Tax

Responding to Dave Roberts’ lament that a carbon tax can’t tackle the climate menace, the Carbon Tax Center’s James Handley and Charles Komanoff articulated the importance of an aggressively-rising tax on carbon pollution to meet the challenge. (Grist, Dec. 4, 2012; also presented as a side-by-side rebuttal of Roberts’ 10 points on CTC’s blog):

Assuming 3 percent annual inflation, a [carbon] tax rising 4 percent a year faster than inflation would take a decade to double in nominal terms, and almost two decades to double in real terms. That’s way too slow a ramp-up, considering that a carbon price of $40/ton of CO2 would add a mere 36 cents to a gallon of gasoline and 1.5 cents/kWh to the average U.S. retail electricity price.

We need a carbon tax that quickly gets to much higher rates than that. It doesn’t have to start like gangbusters; indeed, it shouldn’t, since families, businesses, and institutions all need (and deserve) time to adapt to the new reality of higher fuel and energy prices. A steady and steep ramp-up rate is far more important and beneficial than a high starting point.

These considerations make the ideal carbon tax close to that embodied in legislation introduced in 2009 by Rep. John Larson (D-Conn.). Larson’s carbon tax starts at $15/ton and rises each year by $10-$15, with the actual increment depending on whether emissions are being driven down fast enough. In the 10th year of a carbon tax, the CO2 price would be between $100 and $145 per ton of CO2 under the Larson bill… the market pull (including long-term price expectations) should suffice to elicit cleantech innovation and revolution.

An Emissions Plan Conservatives Could Warm To

Former Representative Bob Inglis and former economic adviser to President Reagan, Arthur Laffer framed the conservative values supporting a carbon tax (New York Times, December 27, 2008):

We need to impose a tax on the thing we want less of (carbon dioxide) and reduce taxes on the things we want more of (income and jobs). A carbon tax would attach the national security and environmental costs to carbon-based fuels like oil, causing the market to recognize the price of these negative externalities.

The market-driven innovation that brought us the Internet and the personal computer could quickly bring us new, cleaner fuels. A carbon tax that was fully offset (with payroll or income taxes cut by a dollar amount equal to the revenues generated by the new tax) would be as bold as the threat that we face.

Conservatives do not have to agree that humans are causing climate change to recognize a sensible energy solution. All we need to assume is that burning less fossil fuels would be a good thing. Based on the current scientific consensus and the potential environmental benefits, it’s prudent to do what we can to reduce global carbon emissions. When you add the national security concerns, reducing our reliance on fossil fuels becomes a no-brainer.

Presentations, Videos, etc

- The Big Picture: Make Polluters Pay (Robert Reich, MoveOn.org). How a carbon tax can slow global warming and improve the economy. (June 2015.)

- Senator Bill Nelson (D-FL) floor remarks (YouTube video) on Pope Francis’ encyclical on climate change. Nelson articulates the climate and economic benefits of revenue-neutral carbon taxes. (June 2015.)

- The Economic Consequences of Delays in U.S. Climate Policy (Brookings, June 2013). (Audio, comments by CTC’s James Handley 1:12 – 1:20).

- Federal Financial Support for Fuels and Energy Technologies (Testimony of Terry Dinan, Senior Advisor, Congressional Budget Office, to House Subcommittee on Energy, March 2013).

- The Decarbonization Revenue Calculator, by CTC’s Charles Komanoff (May 2013).

- Comprehensive Tax Reform and U.S. Energy Policy (Harvard econ prof. Dale Jorgenson testifies to Sen. Finance Committee, June 13, 2012, recommending environmental tax on fossil fuel as part of broad fiscal and tax reform.

- CTC Director Charles Komanoff debates EDF at The New School (NYC), April 2010

- What’s Wrong With the Social Cost of Carbon? (Frank Ackerman, Stockholm Climate Institute, Webinar, 2010)

- Cap and Trade Won’t Cut It (James Handley, interviewed on Real News, 2009)

- Dan Rosenblum on PBS News Hour, April 2007

- An Inconvenient Truth, Al Gore’s consciousness-raising, Oscar-winning (2006) movie

- Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change High-level UK report on the costs of not addressing climate change

- David Suzuki video on climate/carbon tax

- “The Story of Cap & Trade” (Animated, by Annie Leonard)

- Laurie Williams & Alan Zabel’s “Huge Mistake” video

From the Price Carbon Campaign – Carbon Tax Center “Pricing Carbon Conference” at Wesleyan Univ., Nov. 2010

Books

Implementing a U.S. Carbon Tax — Challenges and Debates, Ian Parry, Adele Morris, Roberton C. Williams III, (IMF, Routledge Explorations in Environmental Economics, 2015)

The Case for a Carbon Tax, Shi-Ling Hsu (law professor & economist), 2011. Reviewed here.

Fuel Taxes and the Poor (The Distributional Effects of Gasoline Taxation and Their Implications for Climate Policy), Thomas Sterner, (economist, editor), 2012

Global Carbon Pricing: We Will If You Will (2015). E-book compiling eight papers by David J. C. MacKay, Richard Cooper, Joseph Stiglitz, William Nordhaus, Martin L. Weitzman, Christian Gollier & Jean Tirole, Stéphane Dion & Éloi Laurent, Peter Cramton, Axel Ockenfels & Steven Stoft. The authors, from a variety of viewpoints and disciplines, conclude that negotiating an explicit global price on carbon pollution would unlock global climate negotiations by aligning national self-interest with the global goal of rapidly reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Fiscal Policy to Mitigate Climate Change, Ian Parry, Ruud de Mootj, Michale Keen (economists, editors, IMF, 2012)

Plan B 4.0 (A realistic path to a sustainable future), Lester Brown, 2009

The Reality of Carbon Taxes in the 21st Century, Janet Milne (law professor), 2008

Storms of My Grandchildren, James Hansen (climate scientist), 2010

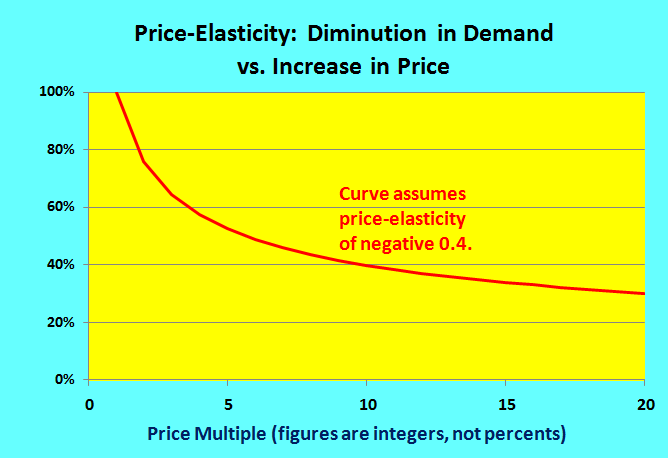

Demand price-elasticity denotes the extent to which rises in price engender a drop in demand. A price-elasticity of 50% means that the drop in demand is half as steep as the price rise. Thus, a 2% increase in price would be required to engender a 1% decrease in demand. Importantly, for large price increases such as we propose over time, the drops in demand would be proportionately less, reflecting the law of diminishing returns. And at the same time the phased-in tax is causing prices of fossil fuels to rise, incomes would be rising, offsetting some of the reductions.

Demand price-elasticity denotes the extent to which rises in price engender a drop in demand. A price-elasticity of 50% means that the drop in demand is half as steep as the price rise. Thus, a 2% increase in price would be required to engender a 1% decrease in demand. Importantly, for large price increases such as we propose over time, the drops in demand would be proportionately less, reflecting the law of diminishing returns. And at the same time the phased-in tax is causing prices of fossil fuels to rise, incomes would be rising, offsetting some of the reductions.

We agree with pioneering climate-scientist

We agree with pioneering climate-scientist

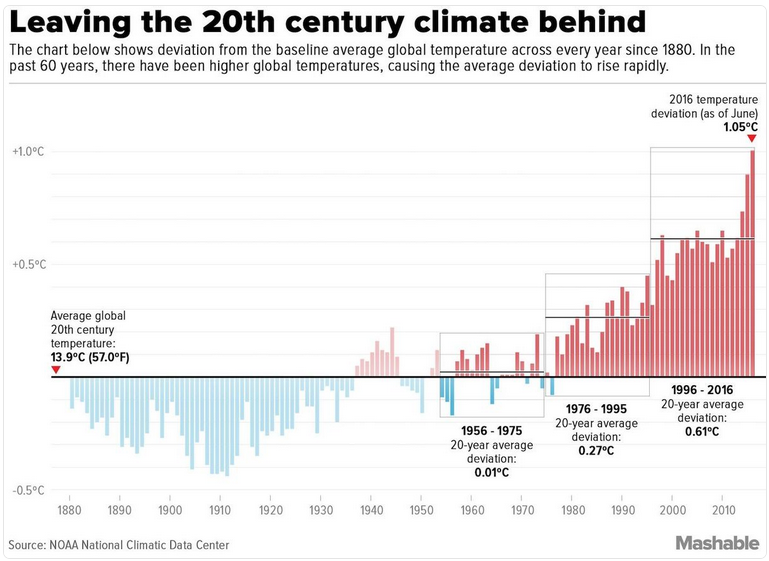

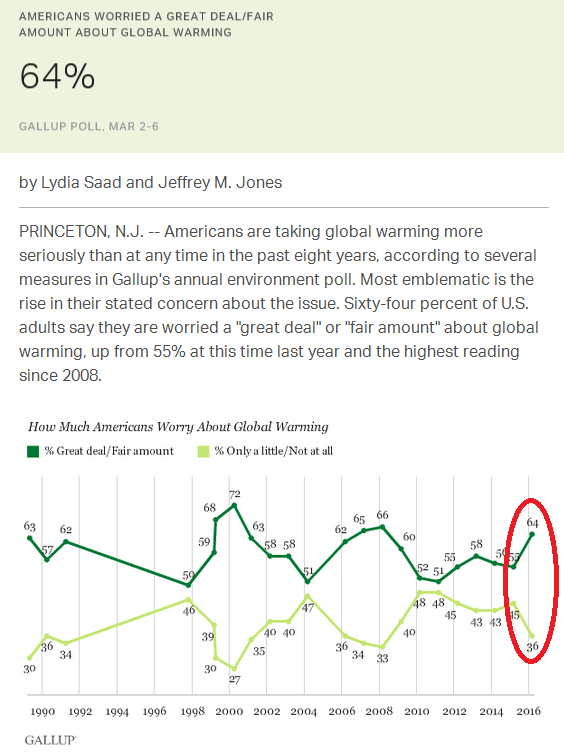

Other results from the 2016 Gallup poll are equally striking. They show a record-high share of Americans stating that climate change poses a threat to them and their way of life; a record number agreeing that climate change is caused primarily by human activity; and climate concern climbing across the political spectrum.

Other results from the 2016 Gallup poll are equally striking. They show a record-high share of Americans stating that climate change poses a threat to them and their way of life; a record number agreeing that climate change is caused primarily by human activity; and climate concern climbing across the political spectrum.