Larson Carbon Tax Mirrored in China Proposal (Financial Post)

Search Results for: larson

New Larson Bill Raises the Bar for Congressional Climate Action

Carbon taxing to safeguard Earth’s climate took several major steps forward — politically and intellectually — with the introduction yesterday of the America’s Energy Security Trust Fund Act of 2009 by Rep. John B. Larson, chair of the House Democratic Caucus and fourth-ranking Democrat in the House of Representatives.

The new bill builds and improves on Rep. Larson’s 2007 bill with these provisions:

- The first-year tax rate is $15 per ton of carbon dioxide.

- The rate rises by $10/ton per year.

- After five years, that increase rate is automatically bumped up to $15/ton if U.S. emissions stray from an EPA-certified glide path to cut emissions by 80% from 2005 levels in 2050.

- To protect domestic manufacturers, the bill authorizes the Treasury Department to impose a “carbon equivalency fee” on carbon-intensive products imported from non-carbon-taxing nations.

- Clean-tech R&D and investments are eligible for $10 billion a year in tax credits.

- Impacted workers and industries are eligible for transition assistance of $7.5 billion in the first year; this is phased out after year 10 but still totals $41 billion.

- All other revenue is tax-shifted to Americans via reductions in payroll taxes.

Rep. Larson, a member of the powerful, tax-writing Ways & Means Committee, appears to have crafted his new bill to counter most if not all salient objections to carbon taxing:

-

To the insistence on emission guarantees: the Larson bill responds to the “quantity-certainty” objection by virtually guaranteeing deep emission cuts. Emissions would fall to 25% below 2005 levels in 2022, according to CTC’s conservative carbon tax-impact model. If that’s insufficient, the automatic tilt to a $15 annual increment will push the 2022 reduction percentage higher (we estimate to 30%), with cuts continuing after. The average annual decline rate in that scenario matches the 2% target rate in most cap-and-trade proposals and kicks in much more quickly, due to the tax’s shorter lead time.

- To concerns about “tax-and-spend”: over the first ten years, 96% of revenues would be returned to U.S. families. The recapture percentage reaches 99% in year 15.

- To fears of eroding U.S. competitiveness: the payroll-tax reductions provide the much-sought “double dividend” of stimulating the economy while encouraging work. The carbon equivalency fees protect against lagging nations stealing market share from U.S. manufacturers.

- To calls for clean-tech R&D and investment: in tandem with the tens of billions in tax credits and other incentives for efficient and renewable energy in the new American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the $10 billion annual allocation will support critical research, demonstration and deployment of energy efficiency and renewables.

- To those in impacted industries and regions: the $41 billion in grants will likewise help workers and communities make the transition to low-carbon and zero-carbon industries.

The Larson bill isn’t perfect; for one thing, the energy-price protections from the payroll tax-shift will need to be extended to non-working families and individuals. But the automatic upward adjustment in the carbon tax rate, if required to meet certified emission goals, is a big step forward, and should help allay concerns of cap-and-trade adherents over any quantity-uncertainty with a carbon tax.

Equally impressive is the Larson bill’s carbon tax level; with an increment rate of either $10 or $15 a ton per year — implying annual increases of at least 10 cents per gallon of gasoline and ¾ of a cent per kWh for electricity on a national-average basis — producers, consumers and intermediaries will be moved inexorably to lower-carbon investments and choices.

What may make the robust carbon tax level politically feasible, in turn, is that only a small and declining fraction of the revenue is earmarked for new programs. As noted, by the tenth year, 98% of incoming revenue (96% of cumulative) will be recycled to workers and their families. This should be attractive to growth advocates, deficit hawks and advocates for working families.

Prospective losers: profligate emitters, oil barons and sheiks, mountaintop miners, and ideologues who regard as anathema governmental action to correct “the greatest market failure the world has seen.” And, oh yes, cynics who said the U.S. could never enact a meaningful carbon tax.

Photo: Flickr / himesforcongress.

Archived Supporters

This page is a catch-all repository of expressions of support for carbon taxes or other forms of carbon pricing by individuals who no longer occupy the positions of influence (as office-holders, editorial columnists, etc.) that they held at the time those statements appeared. For more current expressions, go to the individual pages (Public officials, Economists, Scientists, and so-forth) listed in the pull-down menu under Supporters.)

Public Officials

Former Energy Secretary Stephen Chu

In a February 2009 New York Times interview, Secretary Chu said “that while President Obama and Congressional Democratic leaders had endorsed a so-called cap-and-trade system to control global warming pollutants, there were alternatives that could emerge, including a tax on carbon emissions or a modified version of cap-and-trade.” Chu was one of four Nobel prize winners (he was awarded the Physics prize in 1997) to sign CTC’s Paris letter calling upon the UN climate negotiators to endorse national and global carbon taxes.

Paul Volcker, chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, 1979-1987

Volcker, who died in 2019, was revered in the business and financial community for shepherding the U.S. economy out of the “stagflation” of the 1970s into the long-term boom of the 1980s and beyond, as chairman of the Federal Reserve under Presidents Carter and Reagan (1979-87). Speaking to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in Egypt, earlier this year, he stated: “[The argument that taxes on oil or carbon emissions would ruin an economy is] fundamentally false. First of all, I don’t think [such a step] is going to have that much of an impact on the economy overall. Second of all, if you don’t do it, you can be sure that the economy will go down the drain in the next 30 years,” Volcker said. Referring to the new report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Volcker added:

What may happen to the dollar, and what may happen to growth in China or whatever pale into insignificance compared with the question of what happens to this planet over the next 30 or 40 years if no action is taken… The scientists seem pretty well agreed that [global warming] is still potentially manageable if we act decisively, beginning now into the next decade or so, by taking measures that are technically and economically feasible.

(All quotes attributed to Mr. Volcker, above, are from an article published in the International Herald Tribune on Feb. 6, 2007, US: Economist Paul Volcker Says Steps to Curb Global Warming Would Not Devastate an Economy.)

Senator Bill Nelson (D-FL, 2001-2019)

Pope Francis’ June 2015 encyclical, calling for urgent action to equitably respond to the dangers of global warming and urging policies requiring polluters to pay for climate damage, prompted Senator Bill Nelson to speak out on the Senate floor. Nelson explained the need for a carbon tax whose revenue could be used to reduce other taxes that impede economic growth. (Video.)

Senator Christopher Dodd (D-CT, 1981-2011)

Dodd anchored his 2007 presidential candidacy to a Corporate Carbon Tax. As he explained: “Until you deal with the issue of price, until you impose a corporate carbon tax, we will never get away from fossil fuels. It’s the only way this can be achieved. You have to advocate that if you’re serious about global warming.” (NY Times, 7/24/07.)

Bill Bradley (D-NJ, 1979-1997)

From Bradley’s op-ed, We Can Get Out of These Ruts, in the April 1, 2007 Washington Post (written a decade after he left the Senate):

We also need to change our tax system to reduce our oil dependence. In general, we ought to reduce taxes on things we need, such as wages, and raise taxes on whatever is dangerous to us, such as pollution and resource depletion. We could implement a $1 per gallon gasoline tax; or an equivalent carbon tax … After a few years of adjustment in the case of a gasoline or carbon tax, cars would be more fuel-efficient, so consumers would pay what they used to pay for the same amount of driving, and the broad middle class would continue to pay lower employment taxes. The result would be increasing demand for goods and services; shrinking dependency payments such as unemployment compensation and welfare; lowered social costs, such as crime and avoidable illness; and a more equitable tax system that encourages rising employment.

Congressman John Delaney (D-MD, 2013-2019)

On Earth Day 2015, Rep. John Delaney introduced a discussion draft of his “Tax Pollution, Not Profits Act” that would establish a tax of $30 per metric ton of carbon dioxide or carbon dioxide equivalent, increasing each subsequent year at 4% above the rate of general inflation. Delaney’s proposal would apply revenues to reduce the corporate tax rate to 28%, provide monthly payments to low-income and middle-class households, and fund job training, early retirement and health care benefits to coal workers.

Congressman Henry Waxman (D-CA, 1975-2015)

Waxman, ranking member of the House Energy and Commerce Committee and co-author of the the American Clean Energy and Security Act, a cap-and-trade measure that passed the House in 2009 but failed in the Senate, began seeking public input on a proposal for a much simpler carbon tax in early 2013. With Republicans (many of whom are climate science denialists) wielding the gavel in the House, Waxman’s initiative made little headway. Nevertheless, Waxman’s shift appeared to bode well for efforts to enact simple, transparent carbon taxes without the gimmicks of complex cap, trade and offset schemes.

Congressman Bob Inglis (R-SC, 1993-1999, 2005-2011)

Inglis represented South Carolina’s 4th Congressional District for six terms before losing the 2010 Republican primary to a Tea-Party backed rival. With economist Arthur Laffer, Inglis published An Emissions Plan Conservatives Could Warm To (NY Times, 12/08), calling on Congress to enact a revenue-neutral U.S. carbon tax (emphasis added):

Conservatives don’t support tax increases that are veiled as “cap and trade” schemes for pollution permits. But offer us a tax swap, and we could become the new administration’s best allies on climate change.

A climate-change bill withered in Congress this summer because families don’t need an enormous, and hidden, tax increase. If the bill’s authors had instead proposed a simple carbon tax coupled with an equal, offsetting reduction in income taxes or payroll taxes, a dynamic new energy security policy could have taken root.

As long as national security risks aren’t factored into the cost of gasoline and as long as carbon dioxide can be emitted without penalty, oil will continue to have an advantage over emerging fuels in the marketplace, and we’ll continue our ruinous addiction to it. We need to impose a tax on the thing we want less of (carbon dioxide) and reduce taxes on the things we want more of (income and jobs). A carbon tax would attach the national security and environmental costs to carbon-based fuels like oil, causing the market to recognize the price of these negative externalities.

Conservatives do not have to agree that humans are causing climate change to recognize a sensible energy solution. All we need to assume is that burning less fossil fuels would be a good thing. Based on the current scientific consensus and the potential environmental benefits, it’s prudent to do what we can to reduce global carbon emissions. When you add the national security concerns, reducing our reliance on fossil fuels becomes a no-brainer.

It is essential … that any taxes on carbon emissions be accompanied by equal, pro-growth tax cuts. A carbon tax that isn’t accompanied by a reduction in other taxes is a nonstarter. Fiscal conservatives would gladly trade a carbon tax for a reduction in payroll or income taxes, but we can’t go along with an overall tax increase.

The good news is that both Democrats and Republicans could support a carbon tax offset by a payroll or income tax cut.

Two carbon tax bills introduced in House Ways & Means (tax-writing committee) embodied much of what Rep. Inglis advocated in his op-ed: Stark-McDermott, filed in April 2007, and Larson, filed in August. (More details on our Bills page.) Rep. Inglis now chairs republicEn, (formerly the Energy & Enterprise Initiative at George Mason University) and is a vocal advocate for a revenue-neutral U.S.carbon tax.

Congressman Pete Stark (D-CA, 1973-2013) and Congressman Jim McDermott (D-WA, 1989-2017)

(Former) Congressmen Stark, who died in 2020, and McDermott were lead sponsors of the “Save Our Climate Act,” (2007) that would have imposed a $10 per ton (of carbon) charge on coal, petroleum and natural gas when the fuel is either extracted or imported. The charge would increase by $10 every year until U.S. carbon dioxide emissions have dropped 80% from 1990 levels. Introducing the bill, Congressman Stark eloquently stated:

The question is not if human activity is responsible for global climate change, but how the United States will respond,” said Stark. “Predictable, transparent and universal, a carbon tax is a simple solution to a difficult problem. It would drastically reduce our carbon dioxide emissions by providing an economic disincentive for the use of carbon-based fossil fuels and an incentive for the development and use of cleaner alternative energies. The Save Our Climate Act would establish the United States as a global leader in environmental protection and encourage other nations – most of whom have already acknowledged the climate change threat – to take similar action to reduce emissions. I strongly encourage Congress to pass a carbon tax.

CTC reported on the Stark-McDermott bill here.

Editorial Positions

The New York Times

See our Editorial Positions page for more recent expressions.

Global Warming and Your Wallet (July 6, 2007): “When the market, on its own, fails to arrive at the proper price for goods and services, it’s the job of government to correct the failure… We are now using the atmosphere as a free dumping ground for carbon emissions. Unless we — industry and consumers — are made to pay a significant price for doing so, we will never get anywhere.”

Warming Up on Capitol Hill (March 25, 2007): “Forcing polluters to, in effect, pay a fee for every ton of carbon dioxide they emit will create powerful incentives for developing and deploying cleaner technologies.”

The Truth About Coal (Feb. 25, 2007): “There is a need to put a price on carbon to force companies to abandon older, dirtier technologies for newer, cleaner ones. Right now, everyone is using the atmosphere like a municipal dump, depositing carbon dioxide free. Start charging for the privilege and people will find smarter ways to do business. A carbon tax is one approach. Another is to impose a steadily decreasing cap on emissions and let individual companies figure out ways to stay below the cap.”

Avoiding Calamity on the Cheap (Nov. 3, 2006): “Since the dawn of the industrial revolution, the atmosphere has served as a free dumping ground for carbon gases. If people and industries are made to pay heavily for the privilege, they will inevitably be driven to develop cleaner fuels, cars and factories.”

The Washington Post

See our Editorial Positions page for more recent expressions.

Some Positive Energy — Now Start Talking About a Carbon Tax, (June 25, 2007).

As important as many of the measures in [the Senate energy] bill are, they amount to only tinkering at the margins of a serious problem. What the Senate bill doesn’t do — and what the House bill won’t do when it is brought to the floor for consideration next month — is spark a necessary debate on the imposition of a cap-and-trade system or a carbon tax. This must be on the agenda after the Fourth of July recess when the Senate is expected to take up global warming. Sooner or later, Congress will have to realize that slapping a price on carbon emissions and then getting out of the way to let the market decide how best to deal with it is the wisest course of action.

Sorry Record – Waiting for breakthrough technologies is not the way to reduce greenhouse gases (July 11, 2006)

[The Administration] has resisted taxing carbon use, preferring instead to provide incentives for oil and gas extraction — just the opposite of what’s needed.

Los Angeles Times

See our Editorial Positions page for more recent expressions.

The L.A. Times ran two stirring editorials in May-June 2007 that powerfully made the case for taxing carbon. Here are excerpts:

Time to Tax Carbon, (May 28, 2007):

There is a growing consensus among economists around the world that a carbon tax is the best way to combat global warming, and there are prominent backers across the political spectrum … Yet the political consensus is going in a very different direction. European leaders are pushing hard for the United States and other countries to join their failed carbon-trading scheme, and there are no fewer than five bills before Congress that would impose a federal cap-and-trade system. On the other side, there is just one lonely bill in the House, from Rep. Pete Stark (D-Fremont), to impose a carbon tax, and it’s not expected to go far.

The obvious reason is that, for voters, taxes are radioactive, while carbon trading sounds like something that just affects utilities and big corporations. The many green politicians stumping for cap-and-trade seldom point out that such a system would result in higher and less predictable power bills. Ironically, even though a carbon tax could cost voters less, cap-and-trade is being sold as the more consumer-friendly approach.

A well-designed, well-monitored carbon-trading scheme could deeply reduce greenhouse gases with less economic damage than pure regulation. But it’s not the best way, and it is so complex that it would probably take many years to iron out all the wrinkles. Voters might well embrace carbon taxes if political leaders were more honest about the comparative costs.

Reinveting Kyoto, (June 11, 2007):

A better treaty [than Kyoto] would scrap the unworkable carbon-trading scheme and instead impose new taxes on carbon-based fuels. As recently explained in the first installment of this series [Time to Tax Carbon, above], carbon taxes avoid many of the pitfalls of carbon trading. They would produce an equal incentive for every nation to clean up without relying on arbitrary dates or caps, or transferring money from one nation to another. They’re also much less subject to corruption because they give governments an incentive to monitor and crack down on polluters (the tax money goes to the government, so the government wins by keeping polluters honest)… Real solutions to global warming, such as carbon taxes, won’t come cheap — they’ll make power bills steeper and gas prices even higher than they are now. But the economic news isn’t all bad. Much of the clean technology of the future will probably be developed in the United States and sold overseas. Think of [a carbon tax] as a novel way of reducing our trade deficit with China while building a cleaner world.“

For the strong critique of cap-and-trade in the Time to Tax Carbon editorial, click here.

Other Newspapers

Detroit Free Press:

A tax on carbon dioxide emissions, phased in gradually but relentlessly, would be the most transparent and efficient step this country could take in the search for energy independence and reductions in many emissions, including carbon dioxide. It would send a hugely important signal to the markets — for cars and for alternative energy sources such as windmills and solar collectors, in particular — that innovation and conservation are essential. Consumers are going to pay for any measures taken to reduce greenhouse gases and shift away from dependence on foreign petroleum. But most politicians choose instead to hide the costs by placing expensive demands on automakers and by dispensing subsidies for alternative fuels, such as ethanol, that become a hidden tax burden. A cap-and-trade system for emissions also would have disguised costs. Keep Carbon Tax in the Mix of Solutions, July 12, 2007.

Chicago Tribune:

[T]he ultimate goal should not be to reduce the price consumers pay at the pump. It should be to reduce the amount going to oil producers. Global warming is more than ample grounds for levying taxes on carbon-based fuels, including gasoline, to reduce emissions. But those taxes would fall partly on foreign oil producers. By cutting consumption, they promise to put downward pressure on world crude oil prices—weakening OPEC and stemming the flow of dollars to anti-American regimes. American consumers have a choice: They can pay high prices to oil producers or to themselves. The tax proceeds can be used to finance programs of value here at home or to pay for cuts in other taxes—even as they curb the release of carbon dioxide. Pump Pain, May 20, 2008.

Christian Science Monitor:

Consumption taxes, after all, are often designed to wean people off bad behavior, such as smoking. A 90 percent drop in these emissions is probably what’s needed to limit any rise in atmospheric warming to 2 degrees Celsius, a goal that many scientists recommend. Most presidential candidates do endorse pinching pocketbooks, but only indirectly, such as by calling for higher fuel efficiency in vehicles and a cap on greenhouse-gas pollution from company smokestacks. Such demands on industry have the advantage of creating more certainty in reducing emissions, but they are complex to enforce. Gore would do both: tax carbon use and cap emissions. Putting a crimp on global warming can’t be done solely by promoting new energy technologies and voluntary conservation. Consumers of oil and coal need a direct tax shock. Christian Science Monitor, July 5, 2007.

The Monitor was even more direct in a pair of editorials on Oct. 25 and 26. In the first, Be Wary of Complex Carbon Caps, the Monitor noted the loopholes, fraud and other problems that have hamstrung carbon cap-and-trade programs. In the second, A Tax on Carbon to Cool the Planet, the Monitor summarized the first editorial:

Indeed, caps may put the US on a knowable track to, say, an 80 percent reduction in carbon emissions by 2050. But as the previous Monitor’s View pointed out, the flaws in cap-and-trade plans as experienced in other nations – their complexity and vulnerability to fraud and special-interest lobbyists – would reduce the intended effect. They also take a long time to set up and get working right. And, in the end, they also raise energy prices for consumers, just not as directly as a tax.

The Monitor then concluded:

With Europe’s cap-and-trade system faltering, the US should be a leader in using a carbon tax, even if big polluters such as China don’t follow. As a last resort, the US could tax goods from countries that fail to cut their carbon emissions.

A carbon tax is not the whole solution. Regulations will still be needed, such as stiffer fuel-economy standards for cars and trucks. And the US should fund research into alternative fuels, too. All it takes is the political will to act.

Eugene (OR) Register-Guard:

The crisis presented by global warming demands a response that is simple, comprehensive and effective. A tax on carbon consumption is the only response in sight that both discourages the production of emissions that cause global warming, and finances the rapid transition to a post-carbon economy… “The best way to tax carbon fuels is at the point of production: at the wellhead, mine or biofuel plant. The added tax should be large – starting at the equivalent of $1 per gallon of gasoline, and increasing to the equivalent of $6 per gallon of gasoline over 10 years… The phase-in of high taxes on carbon fuels over 10 years will provide huge incentives for market-financed, market-driven, market-governed development of unsubsidized, safe, sustainable alternate energy sources, far more efficient uses of energy, and other alternate products and methods. (The Cold Truth, July 22, 2007).

Writers & Pundits

Bob Herbert

Writing about Obama’s tepid response to the BP oil disaster in the Gulf Coast, Herbert wrote on June 1, 2010:

[W]henever the well gets capped, what we really need is leadership that calls on the American public to begin coping in a serious and sustained way with an energy crisis that we’ve been warned about for decades. If the worst environmental disaster in the country’s history is not enough to bring about a reversal of our epic foolishness on the energy front, then nothing will.

The first thing we can do is conserve more. That’s the low-hanging fruit in any clean-energy strategy. It’s fast, cheap and easy. It’s something that all Americans, young and old, can be asked to participate in immediately. In that sense, it’s a way of combating the pervasive feelings of helplessness that have become so demoralizing and so destructive to our long-term interests…

We also need a carbon tax. The current crisis is the perfect opportunity for our political leaders to explain to the public why this is so important and what benefits would come from it. (Our Epic Foolishness, June 1, 2010, emphasis added).

John Tierney

Burn, Baby, Burn (“The fairest and most efficient way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions would be with a carbon tax on all fossil fuels,” Feb. 7, 2006; similarly on April 23, 2006, in Cheer Up, Earth Day Is Over). In late 2006 Tierney relinquished his column to focus on science reporting. He featured CTC in his Jan. 24, 2007 blog.

There was a time … when the Republican Party was a hotbed of environmental worrywarts. The last big clean air act of the Bush I administration passed the House 401 to 21. But no more, no more. You’re not going to get any sympathy for controlling climate change from a group that doesn’t believe the climate is actually changing … It’s sort of ironic. These are the same folks who constantly seed their antideficit speeches with references to our poor, betrayed descendants. (“This is a burden our children and grandchildren will have to bear.”) Don’t you think the children and grandchildren would appreciate being allowed to hang onto the Arctic ice cap?

Times Economic Columnist Daniel Akst (“On The Contrary”):

Let’s face it: nothing but drastically higher prices will deter most of us from consuming more carbon-based energy… Of course, it would be nice not to have to rely on cartels and circumstances to make us moderate our consumption. Hefty taxes on carbon-based energy … would be a much better approach. The Good News About Oil Prices Is The Bad News, Sept. 17, 2006.

Wall Street Journal business columnist Holman W. Jenkins Jr.:

… walking upright, with knuckles no longer in proximity to the ground, are advocates — mostly economists — of a carbon tax. A carbon tax would be the efficient way of encouraging businesses and consumers to make less carbon-intensive energy choices. Government would not have to exercise an improbable clairvoyance about which technologies will pay off in the future. There’d be less scope for Congress to favor some industries over others purely on the basis of lobbying clout. (Decoding Climate Politics, Jan. 24, 2007) Note: While Jenkins’ remarks should be taken with a heap of salt (he’s no climate advocate, to put it mildly), his praise for a carbon tax and vitriol toward the new enviro-corporate climate alliance are both striking.

Wall Street Journal Op-Ed Contributor Nicole Gelinas, (Contributing Editor to City Journal):

At the end of the day, a strict cap-and-trade program would have the same effect as a carbon tax, one that’s high enough, eventually, to encourage switching to cleaner generation, but that’s gradually imposed over a decade so that companies have plenty of time to plan. Such a tax would make emissions more expensive; discourage carbon-intensive power generation; and it would allow the market to decide which environmentally more-friendly technologies would be competitive enough to take its place. A tax per ton of carbon would mean higher power prices, too, but without direct subsidies to developing nations by paying for their power-plant upgrades. Nor would a carbon tax create a new multibillion-dollar global commodity whose value would depend on political manipulation. The feds could use the revenues from such a levy to reduce other taxes—including dividend and capital-gains taxes further to spur the massive private investment needed to build the next generation of power generators—while ensuring that they’re also creating a political and regulatory climate to encourage such mass-scale construction. If it’s true that a global warming consensus really exists — and not just in press releases and speeches — politicians and business leaders wouldn’t be afraid to suggest such a tax. They would insist on it. A Carbon Tax Would Be Cleaner, Aug. 23, 2007

Washington Post columnists

E.J. Dionne (in 2011):

Obama should put forward a plan of his own to close the long-term deficit. He should not be hemmed in by his negotiations with congressional Republicans to get the debt ceiling raised. They don’t hold the nation’s credit hostage anymore. He should lay out exactly what he would do and abandon his practice of making preemptive concessions to his opponents. That means Obama should not be shy about urging eventual tax increases, particularly on the wealthy. And let’s be clear: These would not be immediate tax hikes; they’d kick in a year or two from now. Any plausible plan should include at least $2 trillion to $2.5 trillion in new revenue over a decade [largely from additional taxes on the wealthy and super-wealthy]. A carbon tax, partly offset by tax cuts or rebates for middle-income and poorer taxpayers, could provide additional revenue. (Obama: Go Big, Long and Global, Aug. 21, 2011)

Anne Applebaum (in 2007):

I no longer believe that a complicated carbon trading regime — in which industries trade emissions “credits” — would work within the United States … So much is at stake for so many industries that the legislative process to create it would be easily distorted by their various lobbies. Any lasting solutions will have to be extremely simple, and — because of the cost implicit in reducing the use and emissions of fossil fuels — will also have to benefit those countries that impose them in other ways. Fortunately, there is such a solution, one that is grippingly unoriginal, requires no special knowledge of economics and is easy for any country to implement. It’s called a carbon tax, and it should be applied across the board … (Global Warming’s Simple Remedy, Feb. 6, 2007)

Anne Applebaum again (in 2009):

American politicians who really care about climate change — I’m assuming this includes our president, as well as a majority in Congress — should skip the summits and instead ask themselves why the oil and gas prices that started rising a couple of years ago (creating a boom in alternative-energy research) have once again dropped to an artificial low. Why artificial? Because the price of fossil fuels has never reflected their true cost, either environmental or political. It doesn’t reflect the cost of the U.S. military presence in the Middle East. It doesn’t reflect the cost of treating asthma. And it certainly doesn’t reflect the cost of rescuing bits of the coast of Florida that will be submerged by rising sea levels. Raise the taxes on fossil fuels to reflect those costs, and [T. Boone] Pickens’s [wind farm] project, along with many others, will once again be viable.” (The Summit of Green Futility, July 14, 2009)

Sebastian Mallaby:

These days almost nobody asserts that global warming isn’t happening. Instead, we are confronted with a new lie: that we can respond to climate change without taxing and regulating carbon… We already have technologies to cut carbon… The problem is we don’t use them… What matters is not just the technologies we have but the incentives to deploy them. (A Dated Carbon Approach, July 10, 2006)

Automotive columnist Warren Brown:

Why is it now more politically feasible to send our sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, husband and wives to foreign soil to fight and die for oil than it is for us to place higher taxes on the stuff at home to help reduce our wanton use of it? It’s time to tell Congress that we’re not stupid, not hopelessly blind or irrevocably self-centered. It’s time to demand that Congress give us a real energy policy, one that addresses industry and consumers, one that demands we do what we’ve historically done in times of crises — work together, sacrifice together to solve the problem. Bring Consumers into the Energy Equation, July 1, 2007.

Charles Krauthammer:

Unfortunately, instead of hiking the price [of gasoline] ourselves by means of a gasoline tax that could be instantly refunded to the American people in the form of lower payroll taxes, we let the Saudis, Venezuelans, Russians and Iranians do the taxing for us — and pocket the money that the tax would have recycled back to the American worker. This is insanity. For 25 years and with utter futility (starting with “The Oil-Bust Panic,” the New Republic, February 1983), I have been advocating the cure: a U.S. energy tax as a way to curtail consumption and keep the money at home. On this page in May 2004 (and again in November 2005, I called for “the government — through a tax — to establish a new floor for gasoline,” by fully taxing any drop in price below a certain benchmark. The point was to suppress demand and to keep the savings (from any subsequent world price drop) at home in the U.S. Treasury rather than going abroad. At the time, oil was $41 a barrel. It is now $123. But instead of doing the obvious — tax the damn thing — we go through spasms of destructive alternatives, such as efficiency standards, ethanol mandates and now a crazy carbon cap-and-trade system the Senate is debating this week. These are infinitely complex mandates for inefficiency and invitations to corruption. But they have a singular virtue: They hide the cost to the American consumer. At $4, Everybody Gets Rational, June 6, 2008.

Other Publications

Financial Times Columnist Clive Crook:

If ever there were a case for the maxim, get prices right, this is it. The way to curb carbon emissions is to add the environmental cost of carbon to the price of energy. The current oil price offers a good opportunity: when it falls (as it probably will) a carbon tax could be used to set a floor, making the transition to correctly priced energy much easier. Once the price of energy is right, other decisions become simpler, or can be left mainly to the market. There is no need to legislate fuel economy standards or subsidise conservation and low-carbon forms of energy; no need for an emissions trading regime, with all the waste and complexity and gaming that that entails (witness Europe’s experience); no need to scapegoat oil companies or environmentalists; no need to mislead or pander. For sure, the politics is a challenge – but not, I am willing to bet, as hard as conventional wisdom insists. Carbon is bad: tax it and use the money to cut other taxes. A new kind of politician could do something with that. Financial Times Online June 22, 2008.

Clive Crook (again in FT):

In the US, cap-and-trade was dead even before the midterm elections. The Obama administration plans to rely on regulation instead. [B]ut … this micro-regulatory approach will be costly. The bureaucratic overhead will be huge, as producers vie for waivers and other special treatment. Effort and resources will be misdirected… Where, then, should the government concentrate its efforts? No prizes for guessing the answer: introduce a carbon tax. … In the US, many dismiss this as a political impossibility. They are wrong. Whether the country likes it or not, with or without an effective climate change policy, Americans will eventually have to pay more in taxes. The state of the public finances decrees it. However you do the political calculations, this unpopular outcome is inevitable. Therefore, start measuring a carbon tax against the relevant alternatives. At worst, a moderate carbon tax would be no more indigestible than higher income taxes or other revenue-raising options. And, in every important way, it would be the best climate-change policy as well… Compared to EPA action, a carbon tax is simpler, more transparent, less susceptible to rent-seeking and more economical in bureaucratic overhead. It also provides an indicator around which future international co-operation could be organised and explained. After their break in Cancún, if the US and other governments want to get serious, this is where they should look.” Stop Talking and Start Taxing Carbon, Nov. 28, 2010. (emphasis added)

Clive Crook (now, late 2011, in Businessweek):

Quantity targets enforced by treaty don’t foster effective cooperation, they hinder it… to succeed, measures to curb emissions need to be sustained for decades… Binding emissions targets are too rigid… The best instrument for coordinating climate-change efforts is the price of carbon… For most countries, the simplest and clearest way to hit the price target would be with an outright carbon tax. The economic benefits are well known: By letting markets work, a tax achieves a given amount of emissions abatement at the lowest cost. The world needs to cap its greenhouse gas emissions, but there’s no obligation to do this in the most expensive, painful or disruptive way. Climate-change campaigners made a great mistake early on in opposing this approach — arguing, in effect, that sin should be prohibited not taxed, and that cuts of a certain size had to be assured. The cost of this inflexibility is now apparent: Insist on known and guaranteed cuts in emissions, and the wheels of international cooperation turn too slowly. So far, explicit carbon taxes have not been widely adopted (though where they have been, as in British Columbia, they have worked). It’s not only environmentalists who aren’t enthusiastic. In many countries, especially the U.S., conservatives are bitterly opposed as well. A carbon tax, after all, is a tax. Yet with many countries in a fiscal crisis, a carbon tax is more attractive than before. A carbon tax could lift some of the burden from spending cuts and increases in other taxes. As this sinks in, what was once politically impossible may soon be merely hard. Free Markets, Carbon Tax Best Way to Fight Climate Change: View, Bloomberg Businessweek, Dec. 12, 2011.

San Francisco Chronicle columnist Carolyn Lochhead:

One day, someone’s going to put two and two together and discover that East Bay Rep. Pete Stark’s carbon tax could address global warming and budget troubles at the same time. San Francisco pols are ahead of the curve, proposing a gas tax — a close cousin of the carbon tax — to fight global warming… In policy circles, a carbon tax is a no brainer, embraced by lefties like Stark and conservatives like former Bush economic advisor Gregory Mankiw. It’s a highly efficient way to reduce demand for fossil fuels and induce alternative energy supplies by using market forces. That’s also why it gags politicians: it incorporates the true cost of fossil fuel consumption in prices. Polluting consumers would pay too. Two Vultures, One Stone, Oct. 15, 2007.

Newark Star-Ledger Columnist Paul Mushine:

We need a new generation of clean energy that will enable us to be liberated from dangerous dependence on dictatorships, effective in worldwide competition and provide for a much cleaner and healthier future,” says [Gingrich’s] Web site. These “alternative, renewable energies” that Gingrich is promoting sound the same as the mystery oil Pelosi’s pushing. Like ethanol, these fuels can be manufactured only with huge government subsidies. And those subsidies represent an indirect tax on drivers If we’re going to tax drivers, we might as well do it directly. This is a point upon which most free-market economists agree. Unlike politicians, economists are not up for election, so they can tell the truth about cutting oil imports. And the truth is if you want to cut imports, tax the hell out of gas. The imposition of so-called “Pigovian taxes,” named after the late economist Ar thur Pigou, generates lots of revenue that can be used to reduce other taxes, such as the income tax, that are much worse for economic growth. And such taxes also reduce what Pigou termed “externalities,” the externalities in this case being air pollution, traffic jams and reliance on unstable exporters. On Energy, Dems are Daffy, Newt is Nuts, op-ed, Star-Ledger, August 7, 2007.

Chicago Tribune Editorial Board Member Steve Chapman:

The free market is the best system ever created for providing what we want at the lowest possible cost. The way to get affordable amelioration of climate change is to put the market to work finding solutions. To achieve that, we merely need to make energy prices reflect the potential harm done by greenhouse gases. How? With a carbon tax that assesses fuels according to how much they pollute. Coal, having the highest carbon content, would be taxed the most, followed by oil and natural gas. The higher prices for the most damaging fuels would encourage people and companies to use them less and more of other types of energy, including nuclear, solar, wind and biofuels. This approach also would affect all sources — not just cars, which account for only one-fifth of all U.S. carbon dioxide emissions. Saving the Earth Sensibly, Chicago Tribune, April 12, 2007.

Economists almost unanimously agree that if you want to cut greenhouse gas emissions by curbing gasoline consumption, the sensible way to do it is not by dictating the design of cars but by influencing the behavior of drivers. If you want less of something, such as pollution from cars, the surest way is to charge people more for it. A carbon tax or a higher gasoline tax would encourage every motorist, not just those with new vehicles, to burn less fuel—by taking the bus, carpooling, telecommuting, resorting to that free mode of transit known as walking, or buying a Prius. A Wrong Turn on Saving Fuel – Which Energy Efficiency Plans Hold Up to Scrutiny?, reason.com, July 23, 2007.

[T]he GOP doesn’t have to surrender its principles to confront environmental reality. There is plenty of room for disagreement, for instance, about how to combat global warming. The method most congenial to personal and economic freedom is a carbon tax. Instead of putting the government behind favored forms of energy, as the administration likes to do, it would create strong incentives for people to find their own ways to reduce emissions. It would achieve maximum benefits at minimum cost. It could be revenue-neutral, if the receipts were used to pay for other tax cuts. A carbon tax is hardly a liberal idea. Among its proponents are Gregory Mankiw, who headed the Council of Economic Advisers under President George W. Bush, and Douglas Holtz-Eakin, John McCain’s chief economist during his presidential campaign. But Republican politicians have no interest. During hard economic times, that approach may work. But at some point, voters will conclude that global warming and other environmental problems demand solutions. And Republicans will be left wondering why they didn’t come up with any. Republicans vs. the Environment, June 16, 2011.

Atlanta Journal-Constitution editorial-page editor Cynthia Tucker (writing in the Baltimore Sun):

The president should have told Americans years ago that the days of cheap gas were over. If the president had imposed a stiff tax on gasoline at the pump [after 9/11], American motorists would have grumbled, but we would have gotten over it. (Oiloholic Nation Has No Business Lecturing China, April 24, 2006)

Arizona Republic columnist Robert Robb:

Economists have long preferred a carbon tax to a cap-and-trade regimen. A small tax would likely have a large effect. Once the infrastructure for collecting the tax is in place, an increased rate is just a vote away. Even with a small tax, carbon emissions would become an unpredictable variable cost, creating a large incentive to reconfigure production processes to reduce or eliminate them …Politicians frequently ignore the preferences of economists, since economists usually prefer a reduced role for the preferences of politicians … However, if serious action is to be taken on global warming, someone in the political class needs to start paying attention to them. (Cool It on Global Warming, Feb. 7, 2007)

New York Observer Columnist Nicholas von Hoffman:

When they talk about conservation at all — which is almost never — [politicians] talk in terms of new tax deductions when they ought to be talking about imposing new taxes. How about a heavy energy-consumption tax on McMansions?… Similar kinds of taxes could be imposed on whole classes of machines that pour filth into the atmosphere and consume frightful amounts of fuel. (While Politicians Pander, Conservation Is Ignored, May 15, 2006)

Although CTC seeks to tax all carbon emissions, not just those from uses deemed excessive, we share with von Hoffman the view that taxing carbon is more important than subsidizing carbon alternatives.

Toronto Star columnist David Olive:

Carbon taxes are coming … The carbon tax [is] the single most powerful tool for encouraging conservation of the planet’s finite coal, oil and natural gas resources, and for diminishing the role of CO2 emissions in destroying the earth. Only Carbon Taxes Can Rekindle Conservation, March 9, 2007.

Magazines

The New Republic

In theory, if the United States ever got serious about tackling climate change and put a price on carbon–through either a cap-and-trade system or a simple carbon tax–we could put an end to much of this anguished contrarianism. Shoppers concerned about melting icecaps wouldn’t have to scratch their heads and wonder how many food miles a tomato has traveled, or fret about whether a tightly packed ship full of produce from Chile emits more carbon than having everyone haul groceries in their SUVs from the local farm. The climate impact would be reflected in the price, and markets could work their magic. Simple enough.OK, so it wouldn’t be that simple. Carbon pricing and markets alone won’t, for instance, produce better public transportation. Nor will they put an end to the vast array of government policies that subsidize suburban sprawl–which include, among other things, easy financing for roads, tax deductions for large McMansions, and various zoning regulations that can prevent mixed-use living and disfavor walkable town centers. Nor, for that matter, will they get rid of the federal subsidies that prop up the nation’s agricultural system. (On the other hand, a carbon tax might convince voters that these policies should be altered.) Second-Guessing the Conventional Environmental Wisdom — It’s Not Easy Being Green, Bradford Plumer, assistant editor, The New Republic on-line, Aug. 27, 2007.

Atlantic Monthly

Blogger Megan McArdle (“Asymmetric Information”) used the “local food” quandary to discourse on the capacity of carbon taxes to provide honest information on the true carbon costs of consumer purchases:

How much carbon goes into the food we eat? Recently I’ve been beseiged by buy-local fanatics, claiming that if I eat Guatamalan raspberries, I’m killing the earth with the carbon needed to transport them… [T]his … cause[d] me to try to figure out how much energy the various options consume, and frankly, the answer is, I have no clue. There are so many second, third, and eighth order effects that my brain is spinning… Not only has no one done a good analysis of this subject; I don’t think anyone could… That’s why if we’re serious about cutting carbon dioxide emissions, we need a carbon tax, and not CAFE, or other sorts of piecemeal regulatory solutions. The Perils of Buy Local, Oct. 15.

McArdle’s column, including her invocation of free-enterprise philosopher Friedrich Hayek, is worth reading in full.

The Nation

The Nation published a special issue Surviving the Climate Crisis: What Must Be Done on May 7, 2007. It included a strong editorial, Going Green, stating that in order to reach the “necessarily ambitious goal: 80 percent emission reduction in carbon emissions from their 1990 levels by 2050:

We’ll have to discourage emissions by putting a price on polluting gases like methane and carbon. The best way to do that is through taxation, which would be offset by tax breaks to soften the impact on poor and middle-class households and to encourage green job growth and investment. But such ideas face formidable resistance from a political establishment beholden to entrenched interests–the oil and coal industries–that stand to lose out. Those industries have sunk billions of dollars in investments that would depreciate in value if real carbon reduction targets were achieved. Thus, they fight tooth and nail with lies and canards to keep things as they are.

In the same issue of The Nation, financial journalist Doug Henwood wrote:

Given the risk that a climate catastrophe could hit soon and suddenly … we may not have time for mass movements to develop and force elites to do the right thing. They’ve got to get started now, or all could be doomed. But … there are problems with their favorite strategy: cap-and-trade schemes… Already an entire industry has grown up around the trading system — analysts and brokers and traders who hope to make money from the scheme but contribute not much of anything to saving the planet. Also, cap-and-trade permit prices are tremendously volatile, more so even than the stock market. Volatility makes long-term planning very difficult. A far better approach would be to tax carbon. A carbon tax would be simple — gasoline, coal and other fuels would be taxed based on their carbon content — and nearly impossible to evade. It could be introduced quickly, unlike the multiyear phase-in of the complicated EU cap-and-trade system. The tax rate could start low and then increase, to allow energy users to adjust. Unlike the market volatility of CO2 and SO2 permit prices, a carbon tax would be predictable, making it much easier for businesses and consumers to plan ahead. And as Charles Komanoff of the Carbon Tax Center argues, at least part of the proceeds of the tax could be rebated to poor and middle-income households through the income tax system, neutralizing any inequities.” Cooler Elites, May 7, 2007 issue.

Hendrik Hertzberg, The New Yorker magazine

The veteran commentator Hendrik Hertzberg wrote in the Feb. 13 & 20, 2006 issue:

The best way to encourage conservation — and the true sign of a serious energy policy — would be imposing a hefty gasoline tax and raising mandatory fuel-efficiency standards.

Hertzberg broadened this theme in the March 23, 2009 issue:

If the economic crisis necessitates a second stimulus—and it probably will—then a payroll-tax holiday deserves a look. But it’s only half a good idea. A whole good idea would be to make a payroll-tax holiday the first step in an orderly transition to scrapping the payroll tax altogether and replacing the lost revenue with a package of levies on things that, unlike jobs, we want less rather than more of—things like pollution, carbon emissions, oil imports, inefficient use of energy and natural resources, and excessive consumption. The net tax burden on the economy would be unchanged, but the shift in relative price signals would nudge investment from resource-intensive enterprises toward labor-intensive ones. This wouldn’t be just a tax adjustment. It would be an environmental program, an anti-global-warming program, a youth-employment (and anti-crime) program, and an energy program. (emphasis added)

Others

Newsweek columnist Fareed Zakaria:

Both problems [clean energy’s insufficient funding and insufficient incentives] can be solved by the same simple idea—a tax on spewing carbon into the atmosphere. Once you tax carbon, you make it cheaper to produce clean energy. If burning coal and petrol in current ways becomes more expensive because of the damage they do to the environment, people will find ways to get energy out of alternative fuels or methods. Along the way, industrial societies will earn tax revenues that they can use, in part, to subsidize clean energy for the developing world. It is the only way to solve the problem at a global level, which is the only level at which the solution is meaningful. Congress is currently considering a variety of proposals that address this issue. Most are a smorgasbord of caps, credits and regulations. Instead of imposing a simple carbon tax that would send a clear signal to the markets, Congress wants to create a set of hidden taxes through a “cap and trade” system. The Europeans have adopted a similar system, which is unwieldy and prone to gaming and cheating. The Case for a Global Carbon Tax, April 16, 2007.

Newsweek columnist Robert J. Samuelson:

If we’re going to use price to try to stimulate those new technologies, let’s at least do it honestly. Most economists think that a straightforward tax on carbon would have the same incentive effects for alternative fuels and conservation as cap-and-trade without the rigidities and uncertainties of emission limits. A tax is more visible, understandable and democratic. If environmental groups still prefer an allowance system, let’s call it by its proper name: ‘cap and tax.’ Let’s Just Call It ‘Cap and Tax’, June 9, 2008.

Reason Magazine Science Editor Ronald Bailey:

The problem with air pollution—and global warming is a form of air pollution—is that I don’t see a good, easy way to privatize it. The transaction costs are too large. And if you can’t privatize it, you have to regulate it. So now the question is: What’s the least bad way to regulate? And that is why I’ve come out in favor of a carbon tax….For consumers, for inventors, for innovators, a tax offers price stability in a way that the cap-and-trade markets don’t. For example, in the sulfur dioxide market, sulfur permits have ranged in price from $50 a ton to over $1,000 a ton. And for sulfur dioxide, it’s a smaller market. A carbon market would encompass the world.” Reason.com July 2008

Katherine Ellison (The Mommy Brain):

What our kids need to know most is that adults are acting like grown-ups… If we want to show our kids we mean business about global warming, let’s start by ponying up for a carbon tax. Let our children watch us demand this from Washington with the courage and force of the civil rights movement. (Global Warming-era Parenthood, Los Angeles Times, Dec. 23, 2006)

350.org founder and author-journalist Bill McKibben:

There’s another way of saying what is missing here. Almost every idea that might bring us a better future would be made much easier if the cost of fossil fuel was higher—if there was some kind of a tax on carbon emissions that made the price of coal and oil and gas reflect its true environmental cost.” (How Close to Catastrophe?, New York Review of Books, Nov. 16, 2006.) McKibben, author of the classic The End of Nature and a supremely effective and engaged climate activist, has also advocated for carbon taxes in articles in Orion, Grist, Mother Jones and elsewhere.

Vox.com (earlier, Grist) columnist David Roberts:

A carbon tax is a huge deal, a game-changer, and if it’s taking root, even tenuously, it needs to be nurtured. Is This the Right Time to Attack Dingell?, June 2007.

Note, though, that Roberts (who now writes for vox.com) for years has criticized the effort to enact a U.S. carbon tax as politically naive. Our 2012 exchange with him is particularly illuminating.

Former George W. Bush speechwriter David Frum: Writing in The Wall Street Journal on Nov. 9, 2006, Frum urged Bush to send Congress a carbon-tax bill. In his 2008 book, Comeback: Conservatism That Can Win Again, Frum pressed carbon-tax advocacy at greater length:

There is a simpler and better way to encourage consumers to conserve while denying income to producers: Tax those forms of energy that present political and environmental risks — and exempt those that do not. That tax will create an inbuilt price advantage for all the untaxed energy sources, which could then battle for market share on their competitive merits. What would such a tax look like? … It would look exactly like the carbon tax advocated by global-warming crusaders…You don’t have to believe that global warming is a problem to recognize that a carbon tax is the solution. Under the umbrella of a permanent disadvantage for fossil fuels, markets could figure out freely which substitutes made most sense. (p. 129)

Revenue-Neutrality Rises from the Dead

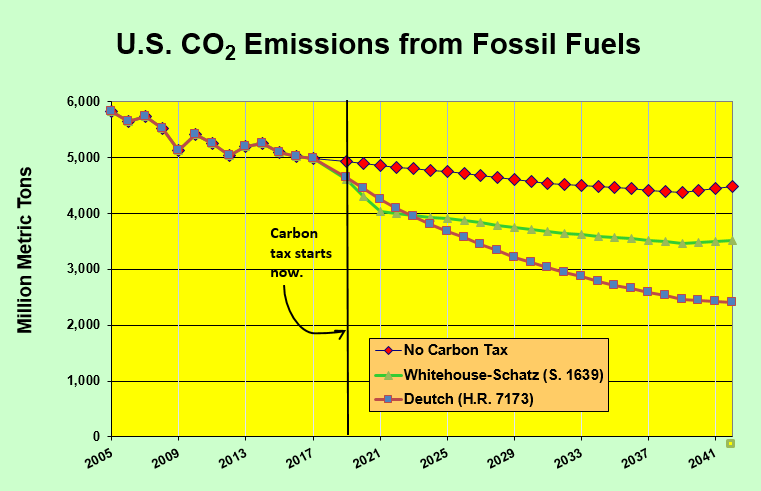

On Wednesday, Rep. Ted Deutch (D-FL) and a small bipartisan group of cosponsors introduced the strongest carbon pricing bill dropped into the Congressional hopper in years. H.R. 7173 closely follows the fee-and-dividend proposal long championed by Citizens’ Climate Lobby, employing not just the dividend template but the robust price trajectory.

The Deutch bill sets an initial tax rate of $15/metric ton, rising by $10/tonne annually thereafter. The increase rate would rise to $15/tonne if annual emissions targets are not met. All of the revenue, net of expenses, would go toward equalized dividends to all American households, based on household size, making the overall proposal revenue-neutral.

H.R. 7173 includes a border adjustment for both imports and exports, to protect the competitiveness of American manufacturing. And it restricts the government’s powers to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, at least for their impact on global warming — a limitation that may be more symbolic than substantive, given the modest emissions impact of President Obama’s signature Clean Power Plan, especially when compared to likely reductions from the new bill’s steep price trajectory.

The Deutch fee-and-dividend bill would surpass the most aggressive recent Democratic carbon tax after five years and would have twice the impact soon after.

The buzz thus far has focused on the bill’s initial cosponsors, two of whom are Republicans: Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA) and Francis Rooney (R-FL). This is not their first trip to the rodeo. Both also cosponsored a much weaker carbon tax bill introduced in July by Carlos Curbelo, who lost his bid for reelection. A third Republican, Dave Trott (R-MI), has since signed on. The two Democratic cosponsors are Charlie Crist (D-FL) and John Delaney (D-MD).

It’s important not to make too much of the bipartisanship on display here. Fitzpatrick, Rooney, and Trott represent an underwhelming 1.5% of the incoming Republican caucus in the House. More particularly, they constitute a mere one-seventh of the surviving Republican members of the all-too-quiescent Climate Solutions Caucus, which is losing most of its GOP contingent to defeat or retirement. Deutch and Curbelo were the founding chairs of the Caucus.

The larger substantive story here is the long-term impact of the Deutch proposal. His $15/tonne starting tax rate is lower than other bills introduced in this session, which range from $24/tonne (Curbelo) to $49/tonne (two Democratic proposals, S. 1639 and H.R. 4209). But the rates in those bills would generally rise by only 2% above inflation annually. Deutch’s proposal, though it starts from a lower base, would outstrip them in impact after just five years, with the differential only widening over time.

According to the Carbon Tax Center spreadsheet model, Deutch’s bill would reduce U.S. CO2 emissions below 2017 levels by 35% in a decade. The best of the Democratic proposals would see a smaller reduction of 25%.

The chances of any carbon tax bill passing in the next Congressional session are close to nil. It is hard to imagine such a proposal getting a floor vote in a chamber led by Sen. Mitchell McConnell (R-Coal Country, aka Kentucky). Even if it did, the veto pen of Donald Trump awaits. Nevertheless, the next two years will allow a debate within the Democratic Party over what its position will be on climate change in the 2020 campaign and, assuming that election goes well for them, in the 2021-22 Congressional session.

The Deutch bill is clearly a contender in that debate. And the more Republican cosponsors Deutch and CCL can recruit this session, the more likely it can become that a robust carbon tax, with revenues going back to American households, will be at least part of the answer.

The other major contender for a Democratic climate program right now is the as-yet-unspecified Green New Deal with major green infrastructure investments possibly funded by a carbon tax. Interestingly, the carbon tax bill with the most support in the House at present, with 21 cosponsors, would also devote most of the revenue to infrastructure, though not specifically green infrastructure. That’s H.R. 4209, the America Wins Act sponsored by longtime carbon tax champion Rep. John Larson (D-CT).

The important thing for carbon tax advocates to remember is that the best bill is the one that can pass. So may the best bill win.

Unicorn or Harbinger? A Republican Carbon Tax Is Readied for Debut.

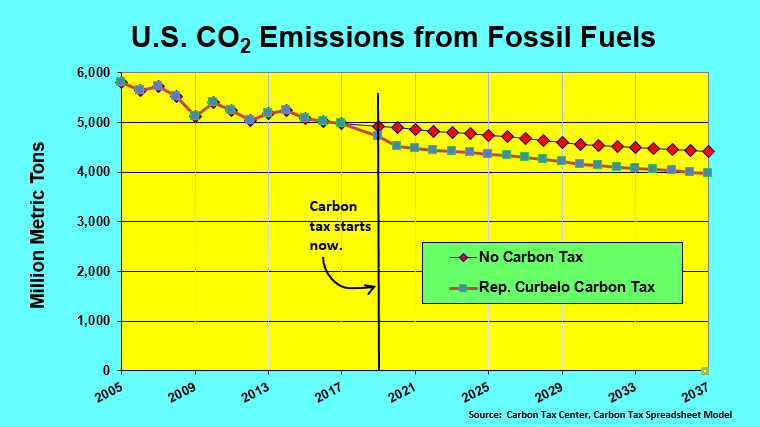

“House Republican will introduce $23 climate fee next week.” That’s the headline of an article today in E&E News reporting that Rep. Carlos Curbelo, a two-term Republican representing Florida’s 26th Congressional District, is finalizing a bill that would impose a carbon-emissions fee on most U.S. fossil fuel-burning sectors and also eliminate or at least pause some federal regulations on climate change.

(Update: The Curbelo bill was introduced on July 23 as H.R. 6463, the Market Choice Act.)

E&E calls Curbelo’s pending bill “a rare effort by a Republican to address global temperature increases by reducing greenhouse gases.” That’s an understatement. To the best of our recollection, the bill would be the first carbon tax proposed by a sitting G.O.P. Congressmember or Senator in roughly a decade.

Any needle-moving from the Curbelo carbon tax would be in the political realm, not in direct emission cuts.

Politically, then, the appearance of Curbelo’s bill will be a big deal. In terms of straight-up carbon reductions, however, the bill is underwhelming. Our quick take from inputting the bill’s key elements into CTC’s carbon-tax spreadsheet model is that in 2020, U.S. CO2 emissions would be 22% below 2005 levels. To put that in perspective, actual U.S. emissions a year ago were 14% less than in 2005; thus, the 2020 bump from the Curbelo bill is at most 8 percentage points — less, actually, given the ongoing decarbonization of our electricity sector. (The Congressman’s draft fact sheet for the bill optimistically pegs the 2020 reduction at 24%.)

By 2032, the emissions drop from 2005 would reach 30% (per Curbelo) or 29% (per our modeling). But seeing as nearly half of that decrease was already in place without a carbon tax in 2017 — a year that is closer to the 2005 base year than to 2032 — the Curbelo proposal has to be seen as fairly thin on actual climate deliverables. Which is what one would expect from a carbon price that barely exceeds $20 per ton (the bill’s $23 starting price is per metric ton) and rises by only 2% a year above general inflation, although the bill contains a provision to ratchet up the increase if reductions fall short of specified targets.

Nevertheless, there’s a bigger picture to consider. Just yesterday we put up a post bemoaning the possibility that the anti-carbon-tax Scalise Resolution would pass, as it did in 2016, without a single Republican dissent. Now it looks like Rep. Curbelo is set to dissent in spades by shattering the decade-long G.O.P. prohibition against sponsoring or endorsing — let alone introducing — a carbon-tax bill.

If any D.C. Republican was going to take such a step, it was likely to be Carlos Curbelo. His 26th CD, extending from southwest Miami to the Everglades and covering the Florida peninsula’s entire southern tip, is a climate ground-zero twice over — sea-level rise plus hurricanes — and a classic swing district (it went blue by double-digits in the last two presidential races). A year after taking his seat in January 2015, Curbelo co-founded the bipartisan Climate Solutions Caucus with fellow Floridian Ted Deutch, a Democrat representing the 22nd CD. Whether by conscience or calculation or a combination of the two, Curbelo clearly read the handwriting and elected to break ranks with his party’s denialist orthodoxy.

The Curbelo bill itself is full of political calculation, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It would clear the books of the long-standing federal highway excise taxes — 18.4 cents per gallon of gasoline, 24.4 cents for diesel. The carbon tax, with its built-in annual increases, would more than make up the difference, though at the cost of a percentage point or two of economy-wide carbon reductions due to the diluting effect of the swap. The Highway Trust Fund would be a big net winner, receiving 70 percent of the entire revenue take. Whether that’s bad or good depends on whether the increased revenue is allocated to highway expansions or “fix-it-first” infrastructure repairs.

G.O.P. carbon-tax trailblazer Carlos Curbelo. Pic credit: Miami Herald.

The bill stands no chance of passage this year, of course, or in almost any imaginable Republican-controlled Congress. Indeed, under the G.O.P.’s Hastert Rule, Rep. Curbelo would need 117 Republican co-sponsors simply to clear the “majority of the majority” threshold and get the bill to the House floor.

If Rep. Curbelo were a Democrat, we would be measuring his bill against Democratic carbon-tax proposals such as Rep. John Larson’s America Wins Act (HR 4209), whose carbon price starts at $49/ton and which devotes $1 trillion to infrastructure (plus transition assistance for coal country and a relatively small “dividend” for households), and which has a few dozen Democratic co-sponsors. And while the Larson bill’s 2%-plus-inflation price increase trajectory has the same slope as Curbelo’s, it operates on a much higher base and thus packs more punch.

But that comparison runs the risk of missing the point: that a “long national nightmare” of Republican silence and inaction on climate may be starting to end. Whether other G.O.P. lawmakers will stand with Curbelo remains to be seen. He is at least blazing a path, and for that he deserves our thanks.

CTC supporter and volunteer Bob Narus contributed research and ideas to this post.

Energy-Efficiency Standards

Since the 1970s, energy-efficiency regulations (generally called “standards”) on appliances, vehicles and buildings have helped save large amounts of electricity and fuel in the United States, largely by forcing product design changes that would not have come about from “market forces” alone.

But energy standards by themselves will never achieve the deep cuts in energy usage needed for the clean-energy transition. Standard-setting takes a long time and invariably involves compromises with powerful industries (automobiles, consumer durables) that lead to confusing and wasteful loopholes. Moreover, standards by nature can handle only one product or usage-sector at a time and tend to be static whereas energy use is ever-evolving, especially in dynamic and “disruptive” late capitalism. In addition, standards provide no incentive for users (drivers, households) to change their behavioral patterns to maximize energy savings.

Carbon taxes combined with efficiency standards will achieve far more than standards alone by encouraging manufacturers and builders to proactively maximize energy efficiency while giving consumers ongoing incentives to make cost-effective choices valuing efficiency in shopping, traveling and purchase of homes and other durables.

We made many of these points in a blog post in September 2015, What an Energy-Efficiency Hero Gets Wrong about Carbon Taxes, from September, 2015. It was one of our most popular posts, and we reproduce it directly below. We hope to add content soon about the limits of automobile mpg standards.

— Charles Komanoff, November 2015

What an Energy-Efficiency Hero Gets Wrong about Carbon Taxes (from Sept 2015)

It’s rare that critiques of carbon taxing are as quantitative as the post last month by David Goldstein on the Natural Resource Defense Council’s Searchlight blog.

Goldstein qualifies as a genuine energy-efficiency hero, in my book. He has spearheaded NRDC’s pioneering analyses of appliance engineering, manufacture and marketing since the 1970s and guided the council’s strategic interventions in utility governance and energy standard-setting in California and at the federal level. This in-the-trenches work has slashed power consumption and carbon emissions from refrigerators, air conditioners, light bulbs and building envelopes in all 50 states. Goldstein’s 2002 MacArthur Foundation “genius award” was richly deserved. (The Washington DC-based American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, ACEEE, merits a shout-out as well.)

Befitting his analytical bent, Goldstein’s critique sticks to the high road. No self-fulfilling taunts about carbon taxers’ naivete or the tax’s political infeasibility. His post does drag out a straw man, though, insisting up-front that “carbon emissions fees alone cannot solve the climate problem” — a position held by few carbon tax advocates. (We ourselves “recommend carbon taxes in addition to energy–efficiency standards.”) His criticism sharpens at the end: “In summary, carbon pollution fees, as a stand-alone policy, are incapable of doing much to solve the climate problem.”

Goldstein has certainly thrown down the gauntlet. He has four main arguments, which I’ll treat in order. Some math is involved, but it’s central to the issue.

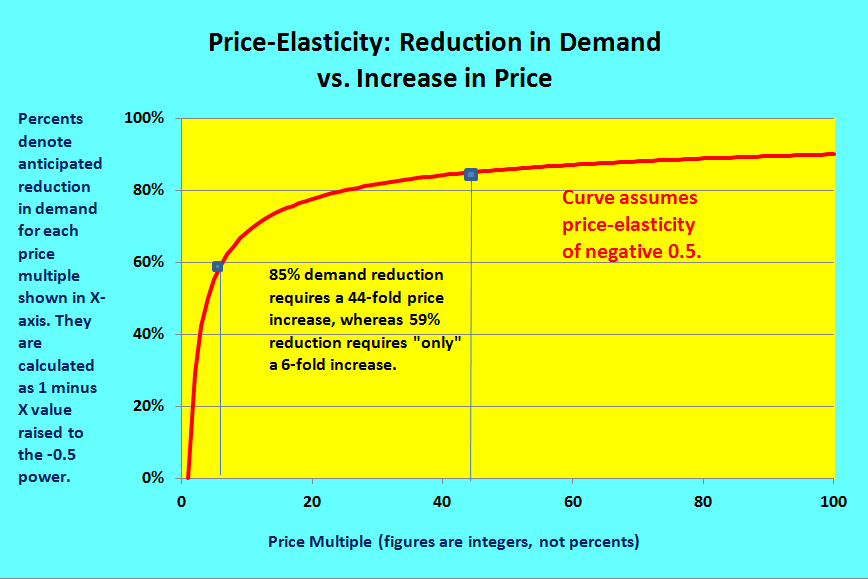

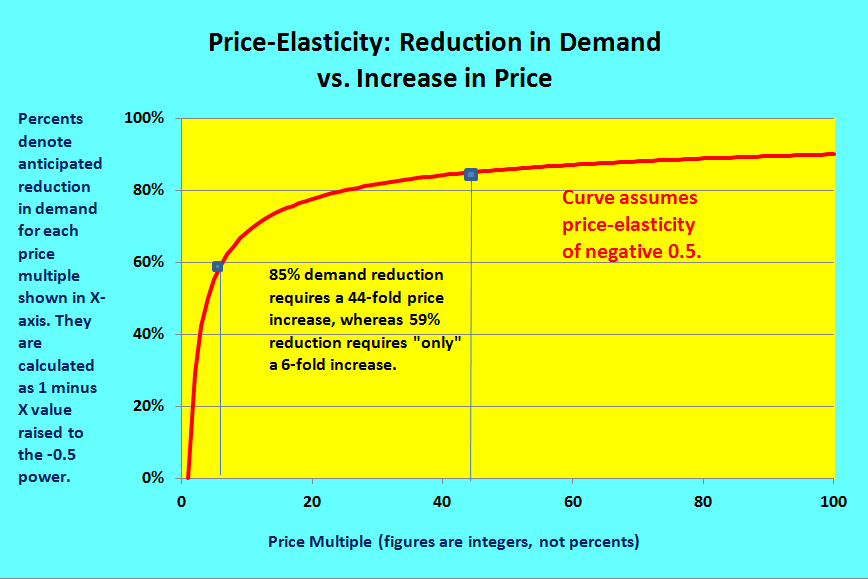

Argument #1: Carbon Taxes Must Raise U.S. Energy Prices 44-Fold to Meet Our Carbon Targets

Let’s start with an assertion by Goldstein that is startling but accurate — mathematically:

If we wanted energy demand to drop by 85 percent [the minimum required for the U.S. to meet IPCC temperature-rise targets] due to price, the math behind elasticities shows that we would require a price increase of 44 times. This is an impossibility condition. (emphasis added)

Price-elasticity is how economists denote the extent to which a rise in price causes demand or usage of a good or service to diminish. Assuming, as Goldstein does for argument’s sake (and as we do in modeling carbon taxes), that the price-elasticities of the various forms in which energy is used in the U.S. have an average value of minus 0.5, then a doubling of energy prices, whether effected through a carbon tax or market fluctuations, will cause energy use over time to shrink by 29 percent. (See sidebar for calculations.) With two doublings in price, the shrinkage would be 50 percent.

Note that the second doubling in price produces less of a decrease in usage than the first, reflecting the famed Law of Diminishing Returns. Indeed, three doublings, increasing the price 8-fold, would only bring about an overall 65 percent drop in usage. To hit the 85 percent reduction target requires a 44-fold energy-price rise. Goldstein’s math is spot-on.

But not the use to which it is put. While an 85 percent reduction in energy use would indeed cure the United States’ carbon obligations (not to mention protect and conserve air, water and land), it far exceeds what’s required, thanks to the ongoing and parallel reduction in the carbon intensity of energy supply. This decarbonization of supply is prominent in energy and climate discourse, and has been evident in the electricity sector over the past decade. Measured as pounds of CO2 emitted per kWh generated, the emission rate for all electricity generated in the U.S. last year was 16 percent less than the rate in 2005. For that we can thank increased generation from lower-carbon natural gas and zero-carbon wind. (Solar electric generation, though growing very fast, started from a tiny base and wasn’t a notable factor in the decarbonization to date.) Energy efficiency has helped as well by reducing the need to fire up high-carbon coal plants.

A carbon emissions tax, which by its nature favors wind and solar over gas, and gas over coal, will help sustain and accelerate this encouraging supply-side trend. Indeed, the price-sensitivities built into CTC’s spreadsheet model imply that energy supply decarbonization will account for an estimated 53 percent of the overall projected CO2 reductions from any carbon tax. This means that reductions in emissions via demand, i.e., conservation and/or efficiency, that are Goldstein’s stock-in-trade need only accomplish a bit under half (47 percent) of the total task.

The relevant math, then, is this: Thanks to supply decarbonization, the U.S. can limit its reduction in energy usage to 59 percent and still achieve the 85 percent CO2 reduction target. While a roughly 60 percent reduction in energy consumption is still a tall order, it’s far less fantastical than 85 percent. Assuming energy price-elasticities average minus 0.5, that 60 percent reduction in usage could be effected with a “mere” 6-fold rise in energy prices. No 44-fold rise required. (See calculations at end of this post.)

The relevant math, then, is this: Thanks to supply decarbonization, the U.S. can limit its reduction in energy usage to 59 percent and still achieve the 85 percent CO2 reduction target. While a roughly 60 percent reduction in energy consumption is still a tall order, it’s far less fantastical than 85 percent. Assuming energy price-elasticities average minus 0.5, that 60 percent reduction in usage could be effected with a “mere” 6-fold rise in energy prices. No 44-fold rise required. (See calculations at end of this post.)

Argument #2: A Carbon Tax High Enough to Be Effective Would Distort the U.S. Economy

To his credit, Goldstein appears to have anticipated my rebuttal above. He posits a 5-fold increase in energy prices, slightly on the easy side of my 6-fold rise, which he then dismisses on three grounds. Each is problematic, however:

1. “Energy would be pushing a fourth of GDP” (vs. today’s share of ten percent or less), says Goldstein, and, thus, would gobble up too much economic activity. The idea of expensive energy colonizing the economy is definitely a concern in a last-gasp laissez-faire economy in which the costly energy arises through “extreme extraction” of oil from the Arctic, deep waters, and tar sands. But a carbon tax would have the opposite effect, obviating most energy exploration, extraction, conversion, transport and combustion, in accordance with the 60 percent decline in usage posited above. In short, a carbon tax will make our society and economy less energy- and fuel-intensive, not more (while the energy barons, with their wealth clipped, will wield less political power).

2. A 5- or 6-fold increase in energy prices “is not politically possible. Electricity at 50 cents a kilowatt hour?,” Goldstein asks rhetorically. “Gas at $12 a gallon?” Here, Goldstein presumes that a carbon tax would lead to those lofty prices overnight, rather than phasing in over decades. In the latter scenario, the impacts will be softened, yet the price signals guiding long-term investments will be loud and clear. The impacts will be tempered further as the improved efficiency of usage lets businesses and households heat, cool, light and move with fewer units of energy. (Ironically, it was Goldstein and his NRDC colleagues who coined the mantra that what matters is electricity bills and not rates. Note also that CTC is on record criticizing proposed carbon taxes that would start with abrupt energy price rises, on account of the likelihood of economic dislocation.)

3. The carbon tax required to boost energy prices 5- or 6-fold “would be potentially devastating to the poor,” Goldstein argues. Potentially yes, if the wealthy are allowed to siphon off the carbon tax revenues that could buffer U.S. households from the higher energy prices. But the carbon tax designs with the most adherents are those that either use the proceeds to reduce regressive job-killing payroll taxes or distribute them pro rata to households as “fee-and-dividends.” In fact, the need for a socially and economically just distribution of carbon tax revenues only underscores the urgency for environmental progressives to coalesce now behind carbon tax legislation that can safeguard the 90 percent rather than solidifying the advantages held by the top 10 or 1 percent.

Argument #3: Energy Demand is Price-Inelastic, So a Carbon Tax Won’t Affect It

Goldstein next revisits energy price-elasticity in an attempt to show that its actual value lies closer to a barely behavior-influencing (minus) 0.1 than the more robust (minus) 0.5 figure he granted earlier for argument’s sake. But curiously, he builds his case on a commodity that no end-user actually purchases: crude oil. Refineries consume crude, of course, but the businesses and households whose decisions determine aggregate demand consume petroleum products: The fuels whose price-elasticities need to be estimated empirically are gasoline, diesel fuel and jet fuel ― not crude oil.