Forget the 1% and the 99%. Forget the 2% and the 98%. The numbers that matter in last week’s fiscal cliff outcome are 77% and $150 billion. The first number, 77%, is the fraction of households whose federal tax burdens jumped January 1. The second number, $150 billion, is the annual loss in GDP projected by economist Nigel Gault and others due to the expiration of the payroll tax “holiday,” a stimulus measure that had reduced employee payroll tax rates from 6.2% to 4.2% for the past two years. By letting the payroll tax “holiday” lapse, Congress slammed the brakes on the halting economic recovery, taking $20/week off the average employee’s take-home pay at time when growth is sluggish and unemployment remains stubbornly high.

The payroll tax hike effectively eliminated the past year’s worth of wage gains in one month.

The payroll tax, which funds Social Security, is withheld from wages up to $113,000. Two years ago, the Congressional Budget Office pointed out that cutting payroll taxes is a cost-effective spur to job growth and consumer spending, offering more stimulus per dollar than most other kinds of government “spending.” Moreover, it’s the kind of stimulus policy conservatives like; putting money in consumers’ hands, not government contractors’. (Which helps explain why the payroll tax holiday was extended last year with bipartisan support.)

The payroll tax, which funds Social Security, is withheld from wages up to $113,000. Two years ago, the Congressional Budget Office pointed out that cutting payroll taxes is a cost-effective spur to job growth and consumer spending, offering more stimulus per dollar than most other kinds of government “spending.” Moreover, it’s the kind of stimulus policy conservatives like; putting money in consumers’ hands, not government contractors’. (Which helps explain why the payroll tax holiday was extended last year with bipartisan support.)

Cutting wage taxes to stimulate economic activity makes intuitive sense: higher take-home pay spurs employment and spending. Similarly, raising taxes on fossil fuels makes sense: we want less pollution, especially CO2 that’s disrupting the global climate system. Even skeptics of global warming science want to breathe less smog, soot and mercury that cause respiratory illness and cancer.

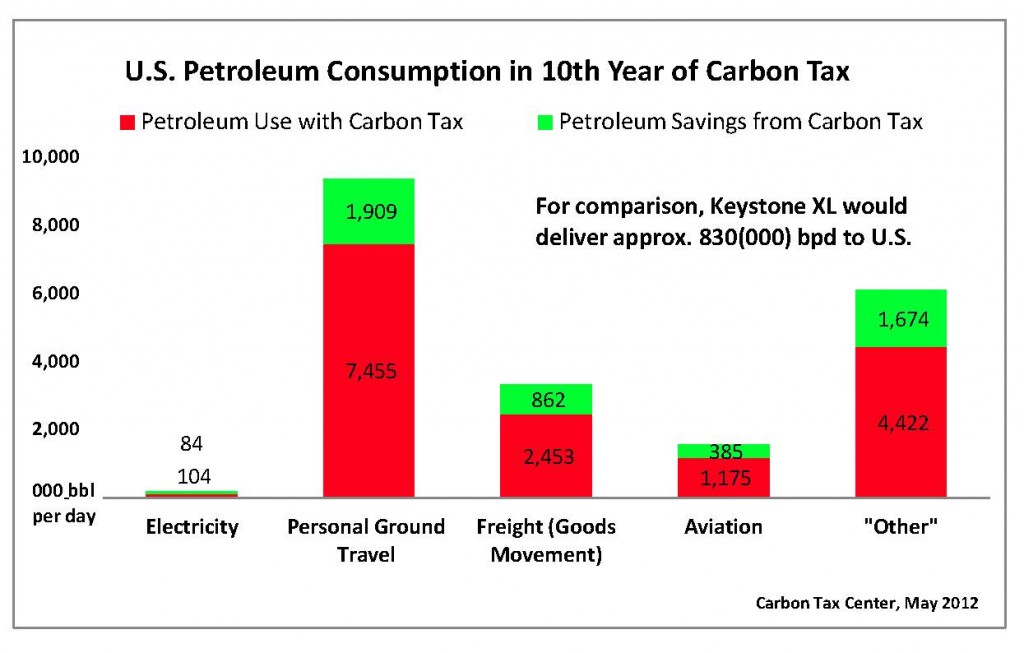

Cutting taxes on work and raising taxes on CO2 pollution can push and pull together: the revenue stream from a modest starter tax of $25 per ton of CO2 would more than fund permanent extension of the 2% payroll tax holiday. This use of the carbon tax revenue would compensate for the potentially regressive effects of carbon taxes. But why stop there? By briskly ramping up the carbon tax to $140/ton over the next decade, we could simultaneously eliminate both employer and employee payroll taxes; a permanent 12.4% pay raise. That’s a big push toward higher employment and a huge downward pull on carbon pollution. As workers cost less and dirty energy costs more, clean energy and efficiency innovators and entrepreneurs will invest and hire where they find opportunities. “Green” jobs without a bureaucracy to oversee special programs. And no increase to overall tax burdens or deficits; it’s a revenue-neutral tax shift, and about as good as it comes.

It is true that the 2011-2012 payroll tax “holiday” required replacing Social Security funds out of general revenue (increasing the federal budget deficit), which some fear compromises the integrity of the Social Security Trust Fund. The worry is that replacing lost revenue with general revenue violates the separate “lock box,” which if extended could effectively reduce retirees who’ve paid into Social Security into just another set of claimants on the federal treasury.

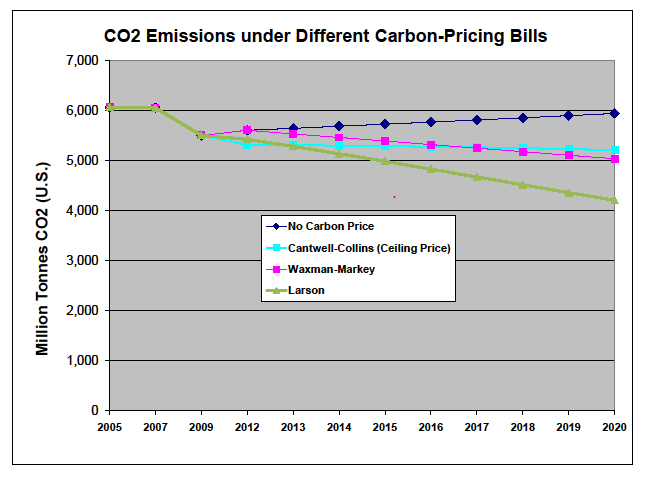

But there are ways to sidestep this important “integrity” concern. A sterling example is the bill introduced in 2009 by Rep. John Larson (D-CT). It’s a briskly-rising tax on carbon pollution (reaching $140/T CO2 in ten years) that applies the revenue to reimburse payroll taxes through a federal income tax credit. Thus, Larson’s proposal wouldn’t touch the Social Security Trust Fund. The structure could easily be expanded to reimburse both employers’ and employees’ payroll taxes as the carbon tax rises annually. At the end of a decade, we’d have pushed up effective wages by 12.4%, while pulling down CO2 pollution by around one-third. All by smartly shifting taxes, not adding to total tax burdens.

Cartoon: Tom Toles, Washington Post 12/9/12

economists who’ve considered the question, I’m convinced that a clear, transparent, gradually-increasing price on carbon pollution is essential to spur energy conservation as well as development and implementation of alternatives to fossil fuels. A carbon tax, with revenue recycled directly to households to build political support and mitigate the economic impacts of what portends to be a decades-long trek to a low carbon economy, offers a real “game changer” to move broadly enough to substantially mitigate climate catastrophe.

economists who’ve considered the question, I’m convinced that a clear, transparent, gradually-increasing price on carbon pollution is essential to spur energy conservation as well as development and implementation of alternatives to fossil fuels. A carbon tax, with revenue recycled directly to households to build political support and mitigate the economic impacts of what portends to be a decades-long trek to a low carbon economy, offers a real “game changer” to move broadly enough to substantially mitigate climate catastrophe. The House

The House  In their seminal report last February, “

In their seminal report last February, “