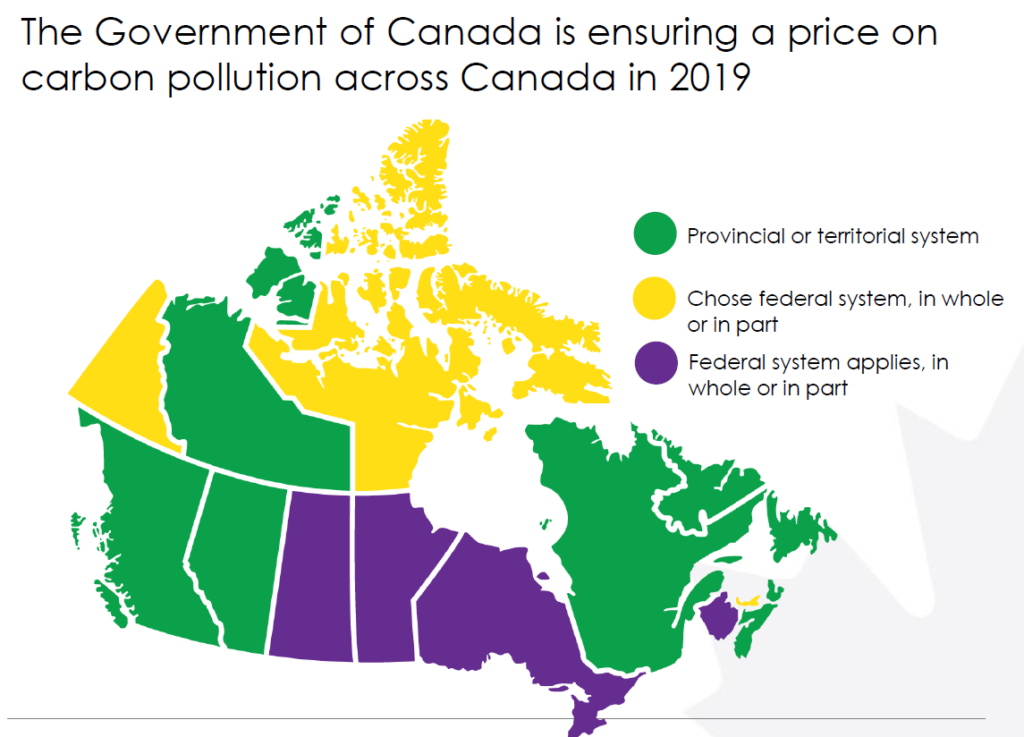

This post from Oct. 24 was amended on Oct. 25 to add the map and reference to David Roberts’ Vox post on the Trudeau carbon pricing plan.

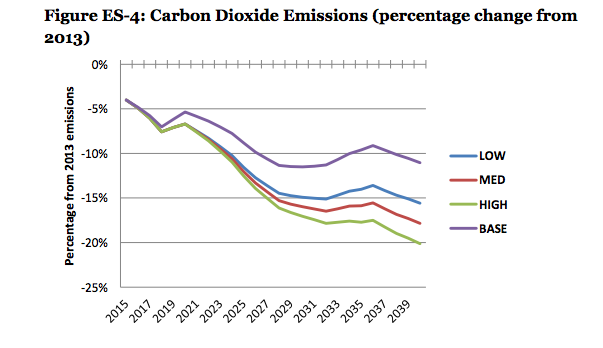

The government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau yesterday announced a national carbon pricing plan that it hopes will yield annual CO2 emissions cuts of 50 to 60 million metric tons by 2022, around a 10 percent drop from Canada’s current emissions.

The plan employs a national carbon price benchmark of $20 (Canadian) per metric ton beginning next year, rising by $10/tonne per year to reach $50 in 2022, according to tables published by the Canadian Department of Finance. Factoring in the 9.3 percent lesser weight of a short ton vis-a-vis a metric ton and the 23 percent lesser value of a Canadian dollar vs. a U.S. dollar, the price trajectory in U.S. terms is $14 per (short) ton, rising by $7/ton per year to reach $35 in 2022.

Map from Canada’s Ministry of Environment & Climate Change outlines Ottawa’s three-prong approach to bring all provinces within a common carbon price.

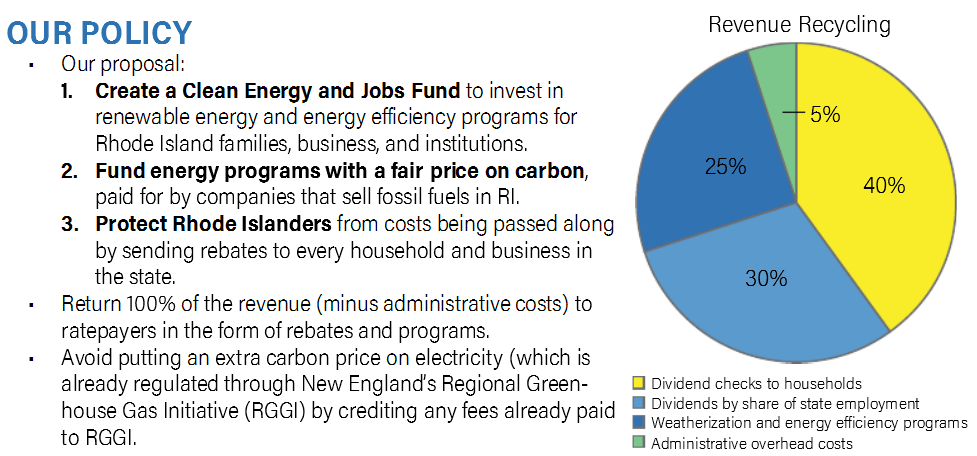

Perhaps the most innovative element of the plan is the “return” of virtually all of the carbon revenues as dividends to households rather than using the monies to pay for tax swaps or green investments. The plan thus embodies the fee-and-dividend idea long espoused by Citizens Climate Lobby and more recently re-branded as carbon dividends by the Climate Leadership Council, the group fronted by retired Republican officials James A. Baker III and George Shultz.

Ottawa’s dividends proposal includes these provisions:

- The dividends, called “climate action incentive payments,” will be provided annually to federal-taxpaying households by the Canada Revenue Agency.

- Residents of small communities and rural areas get a 10 per cent revenue supplement “in recognition of their specific needs” — presumably, higher fuel needs for heating and driving.

- The dividend amounts will vary by province, presumably with individuals and families of high-carbon provinces receiving larger payments.

“Canada needs to cut its greenhouse gas emissions, and the best way to do that is to put a price on carbon pollution,” declared the country’s Department of Finance in a statement yesterday. “Experts, including Nobel Prize winning economists, have made it clear that pollution pricing is the most effective and efficient way to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions that are giving rise to climate change,” said the statement, which added:

Carbon pollution is not free. Canadians see its effects when extreme weather threatens their safety, their health, their communities, and their livelihoods. They pay for it in the form of structural repairs and higher insurance premiums, food prices, health care costs and emergency services. Climate change is expected to cost Canada’s economy $5 billion annually by 2020.

Several Canadian provinces have already implemented carbon pollution pricing, via a tax (British Columbia) or permit systems via cap-and-trade (Quebec, Ontario, most of the Maritime provinces). The fuel levies published this week by the Trudeau government will now undergo a consultation process expected to last at least several months.

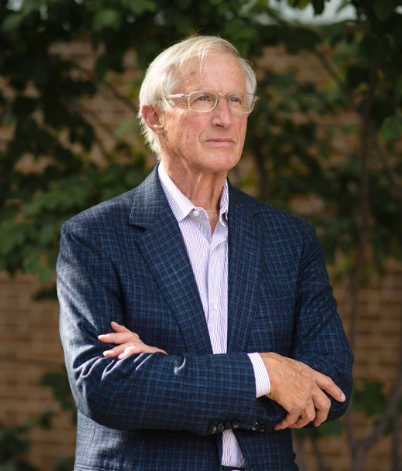

Yesterday’s Finance Dept release includes these three “quick facts”:

- Carbon pollution pricing is the most effective and efficient way to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions associated with climate change.

- Carbon pollution pricing delivers economic benefits because it encourages Canadians and businesses to innovate, and to invest in clean technologies and long-term growth opportunities that will position Canada for success in a cleaner and greener global economy.

- Once in place, carbon pollution pricing could cut Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions by 50 to 60 million tonnes [metric tons] in 2022.

Screenshot from Dept of Finance materials released yesterday as part of Canada’s carbon price policy rollout. Link is at bottom of post.

Total Canadian CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels were estimated at 549 million tonnes in 2015, according to an international listing compiled by the Union of Concerned Scientists. Assuming the targeted reductions in the last bullet point above are all CO2, the 50-60 million tonne reduction would amount to 10 percent of those emissions. (U.S. 2015 emissions were estimated at 4,998 million tonnes in the UCS listing, though our figure for that year was 2 percent greater.)

By 2022, annual carbon revenues under the plan could be as much as $27 billion (Canadian) or $21 billion (U.S.), although exemptions for trade-exposed energy-intensive sectors and for aviation fuel used in indigenous communities might reduce those figures.

The plan is a daring gambit for PM Trudeau, as David Roberts of Vox explained in a post today, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is betting his reelection on a carbon tax.

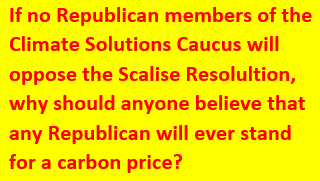

The Canadian government’s embrace of household dividends could also provide a shot in the arm for dividends advocates in the U.S., whose credibility has faltered as Congressional Republicans have disdained the supposedly GOP-friendly dividends approach. This morning, Thomas Friedman, a leading champion of bipartisan climate action among U.S. pundits, called on readers of his New York Times column to “vote for a Democrat, canvass for a Democrat, raise money for a Democrat, drive someone else to a voting station to vote for a Democrat” in the midterm elections.

Echoing Friedman’s call, a constituent of Rep. Carlos Curbelo, the Republican Congressmember who broke ranks with his party in July by introducing a carbon-fee-and-dividend bill, told a Times reporter that Curbelo’s climate concern wasn’t enough to win his vote on Nov. 6: “He is unable to overcome the extreme wing of his party. We need to change the team.”

For more information on Canada’s carbon-pricing plan:

- Document from which we drew our screenshot, “How we’re putting a price on carbon pollution.”

- Press release from office of Prime Minister Trudeau (with links to details).

- Carbon price fuel-charge rates.

- Materials on carbon pricing from Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission.

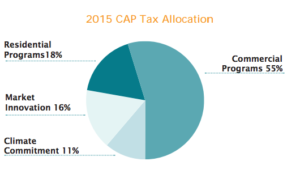

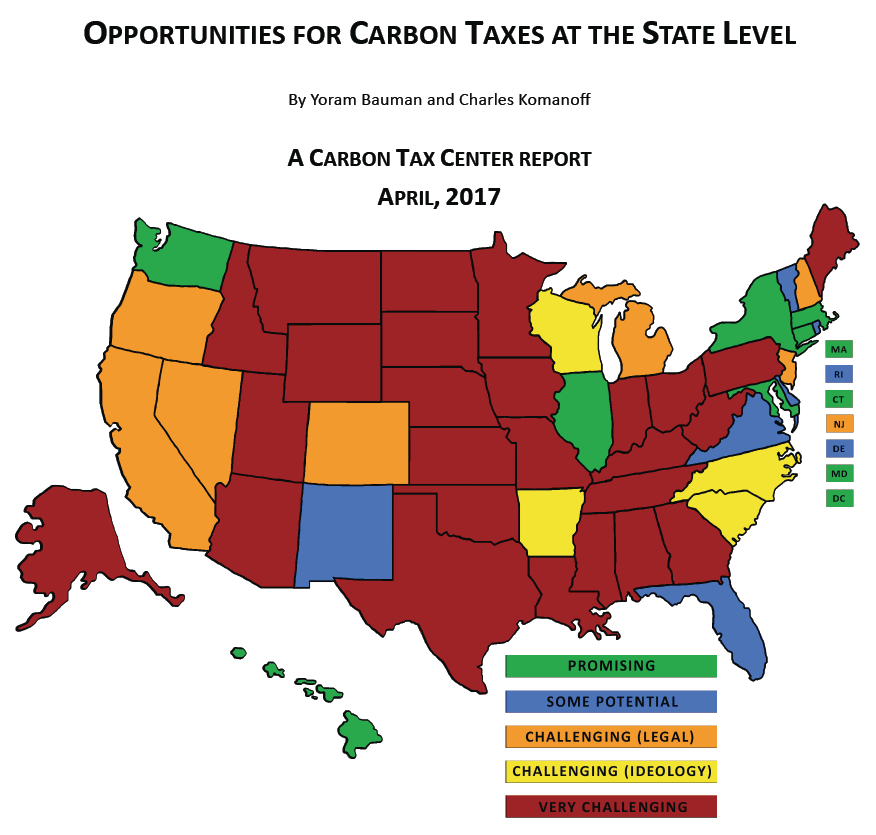

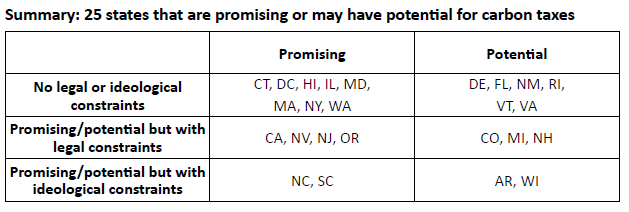

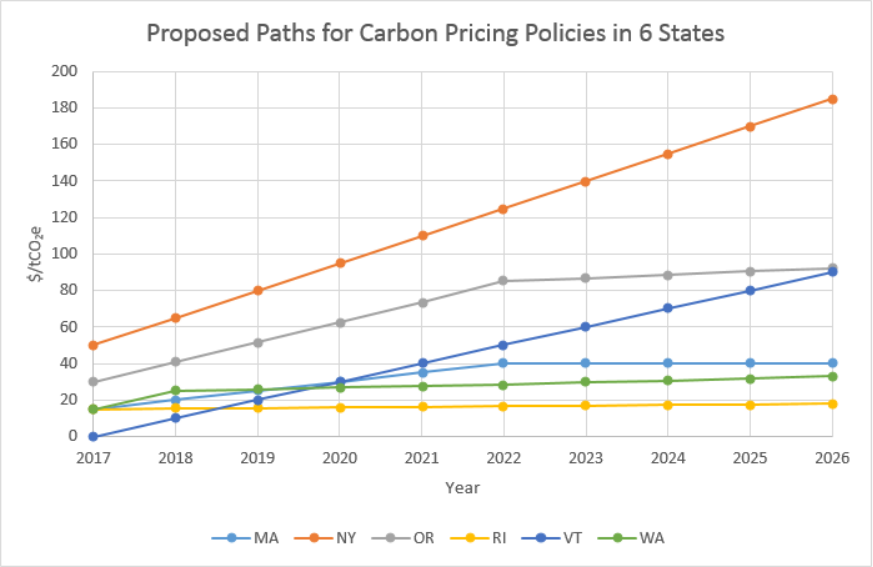

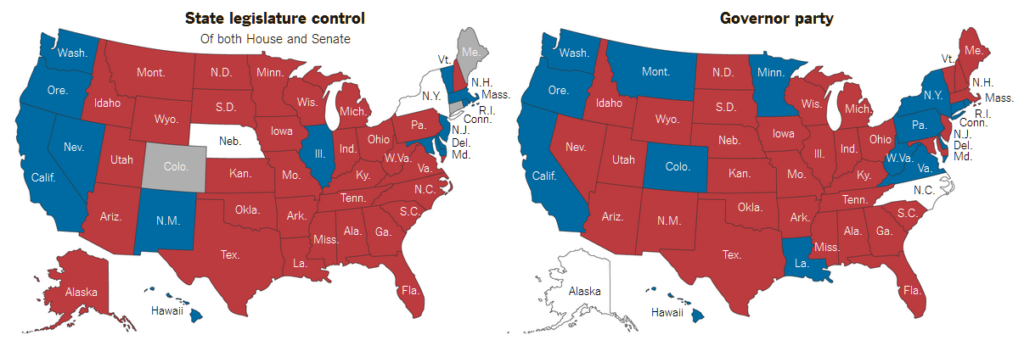

With a national carbon tax blocked by the denialist Republican majority in Congress and a carbon-besotted White House, a growing number of climate advocates are heeding Justice Brandeis’s advice and are organizing at the state level. “Retail” politics, it is thought, might assuage concerns over outside-the-box ideas like carbon taxing, perhaps as occurred in the successful push for marriage equality (the right to same-sex marriage) which began and spread as state-level campaigns.

With a national carbon tax blocked by the denialist Republican majority in Congress and a carbon-besotted White House, a growing number of climate advocates are heeding Justice Brandeis’s advice and are organizing at the state level. “Retail” politics, it is thought, might assuage concerns over outside-the-box ideas like carbon taxing, perhaps as occurred in the successful push for marriage equality (the right to same-sex marriage) which began and spread as state-level campaigns.

The first assertion ignores the possibility of

The first assertion ignores the possibility of