Carbon-dividend proponents continue, as ever, to push for national “fee and dividend” legislation. Today the Washington, DC-based Climate Leadership Council announced formation of a lobbying arm, Americans for Carbon Dividends, headlined by former Senate Republican majority leader Trent Lott, former Senator John Breaux (D-LA) and former Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen. This follows the news last month that the Climate Solutions Caucus — a project spearheaded by the grassroots Citizens Climate Lobby — has enrolled four new Republican House members, bringing total membership to 78 — 39 R’s and 39 Dem’s (with each new Republican, a Democrat is brought in from a waiting list).

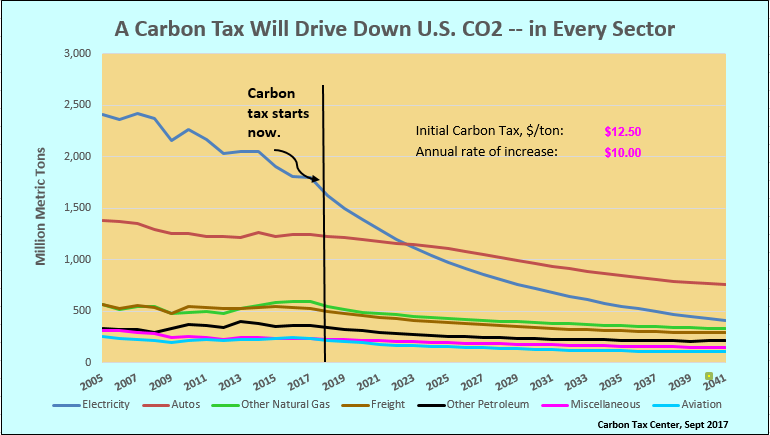

If tenacity trumped reality, CLC and CCL would now be refining their fee-and-dividend proposals into Congressional bills and shepherding them through hearings, markup and, ultimately, legislation. Within a decade of enactment, the money-saving and profit-driven replacement of carbon-belching coal, petroleum and natural gas by low- and zero-carbon fuels, technologies and cultural norms would have pushed U.S. carbon emissions 27 percent below current levels and 36 percent below 2005, the standard baseline year in climate analysis, easily fulfilling our country’s Paris climate pledge. (Figures are based on our modeling of U.S. energy, assuming CLC’s recommended starting CO2 price of $40 per ton, followed by annual rate increases of $5/ton; details here.)

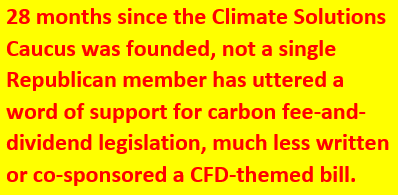

So much for the premise of bipartisanship built into the political strategy for carbon fee-and-dividend.

Alas, reality doesn’t bend so easily. Especially when it comes in the guise of a Congress ruled by, as it is often said, Earth’s only major political party (among democratically run countries) that has sworn itself to disbelieve in human-caused climate change and to disavow the necessity or possibility of public policy to combat it. At this writing, 17 months into the Trump administration and 28 months since the Climate Solutions Caucus was founded, not a single Republican member has uttered a word of support for carbon fee-and-dividend legislation, much less written or co-sponsored a CFD-themed bill — even though, from the outset, the political strategy behind CFD has been built on bipartisanship.

By the same token, the impressive list of Republican luminaries standing with CLC/ACD consists entirely of former office-holders: former Sen. Lott, former Reagan and Bush-41 cabinet secretaries James Baker and George Shultz (the latter’s cabinet service actually extends back to the Nixon presidency), and others whose glittering credentials are shown on the CLC and ACD web sites.

This isn’t meant to disparage these organizations or individuals (excepting current GOP office-holders). We have written glowingly of the fee and dividend concept for a decade, including last year in articles in The Nation and the Washington Spectator. Both pieces praised the Climate Leadership Council’s advocacy, as have our numerous blogs (here, here, and here, inter alia). We were honored to gain George Shultz’s signature on our 2015 Call to Paris Climate Negotiators: Tax Carbon, and are stirred that, in his 98th year, Secretary Shultz continues to devote himself to climate sustainability on behalf of both CLC and Citizens Climate Lobby. We have also worked closely with CCL since its formation in 2009, fielding hundreds of queries from CCL activists on tax incidence, energy modeling and other “technical” matters and gratefully accepting financial contributions from CCL members as well.

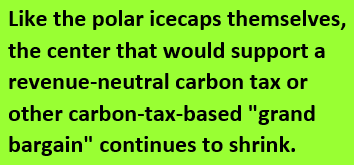

So it’s with a measure of sadness that we share here our sense that the time for carbon dividend proposals has probably passed. The center to which Baker-Shultz (CLC) and fee-and-dividend (CCL) were designed to appeal barely exists. It’s not just that no sitting Republican has endorsed Baker-Shultz or indeed fee-and-dividend in any form. It’s also that the Democratic majority that will be needed to pass a carbon tax bill appears unlikely to rally around a revenue-neutral carbon tax, whether it’s organized as fee-and-dividend or some form of tax swap.

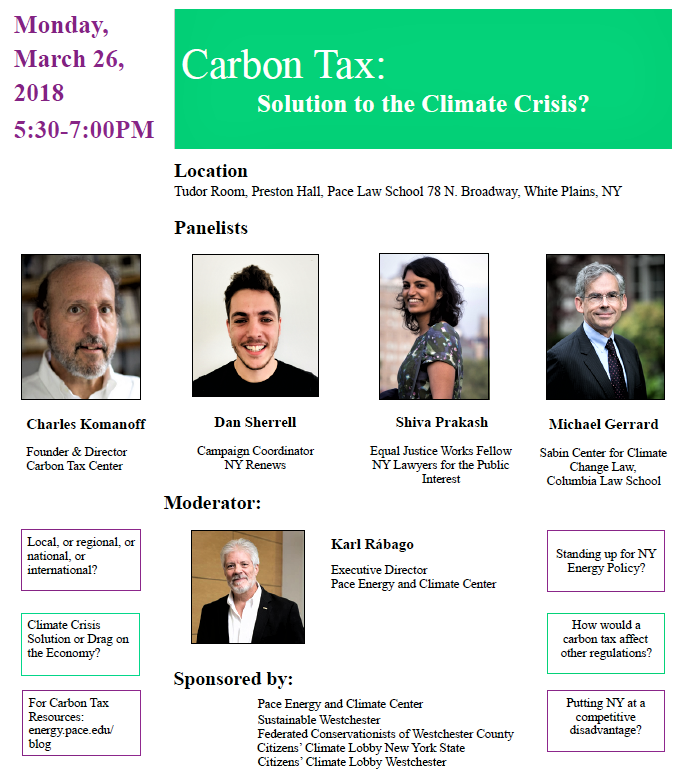

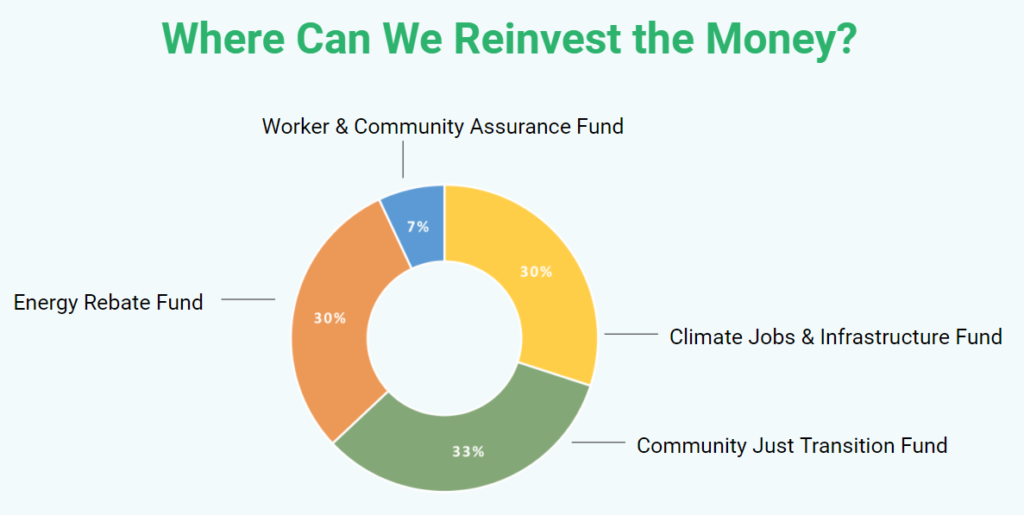

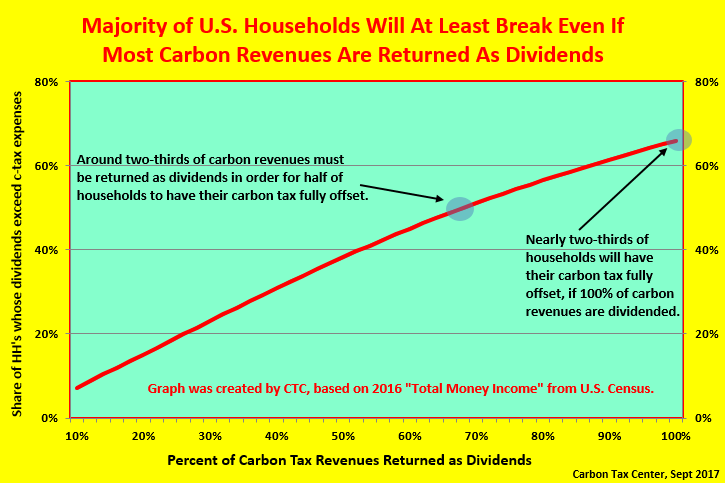

To be sure, the Democratic majority’s carbon tax — if and when there is one — may include a degree of “dividending,” but only of a portion of the revenues. That’s because a Democratic carbon tax bill will also insist on directly investing much of the carbon revenues: in renewables, energy-efficiency, mass transit, worker resettlement and retraining, and damage mitigation — rather than relying on the price pull from the tax. (A textbook example of such a “just transition” bill is the state carbon tax proposal developed by NY Renews, the energetic left-leaning grassroots coalition in New York State.)

There’s nothing wrong with that, provided such a carbon tax can pass and that its tax level rises quickly enough over time to overcome the lesser price-sensitivities (“elasticities”) that govern driving, freight, air travel and the like, which make it harder for carbon-pricing to drive down emissions in the economy’s non-electric sectors. But of course a good deal of the intended appeal of carbon dividend plans was that households, with politicians following in their wake, might support raising the carbon tax because the size of their dividend checks would rise in tandem. Diluting the dividends weakens the appeal.

And revenue-neutrality isn’t the only flashpoint lurking in the CLC-ACD proposal. Another element of the deal — one that has won a measure of oil-industry support — would immunize fossil fuel companies against litigation seeking to hold them accountable for climate damage caused by their products. Earlier today, a leading strategist and backer of such litigation, Lee Wasserman of the Rockefeller Family Fund, told the NY Times that “We categorically oppose any deal that shoves trillions in costs down the throats of innocent taxpayers and lets the companies skip away to profit and deceive another day.”

And revenue-neutrality isn’t the only flashpoint lurking in the CLC-ACD proposal. Another element of the deal — one that has won a measure of oil-industry support — would immunize fossil fuel companies against litigation seeking to hold them accountable for climate damage caused by their products. Earlier today, a leading strategist and backer of such litigation, Lee Wasserman of the Rockefeller Family Fund, told the NY Times that “We categorically oppose any deal that shoves trillions in costs down the throats of innocent taxpayers and lets the companies skip away to profit and deceive another day.”

While sentiments like Wasserman’s help rouse the climate base, they don’t point to a policy solution. Like the polar icecaps themselves, the center that would support a revenue-neutral carbon tax or other carbon-tax-based “grand bargain” continues to shrink. As the horrors of the Trump administration and its Congressional Republican enablers continue to mount, there’s no apparent middle ground, whether in climate and carbon-taxing or in any consequential policy-making.

We can commend the ACD initiative — which former Senators Lott and Breaux have detailed in a New York Times op-ed — while bemoaning its lack of political currency. The political struggle to contain climate change has moved to the courts and to the state and local levels. If and when a semblance of sanity returns to Congress and the White House, that state and local mobilization will be critical to enacting the carbon tax and complementary policies necessary to achieve deep cuts in emissions.

Note: A month after we published this post, Rep. Carlos Curbelo (FL-26), introduced a carbon-tax bill — the first from a Republican member of Congress in a decade — as we reported here.

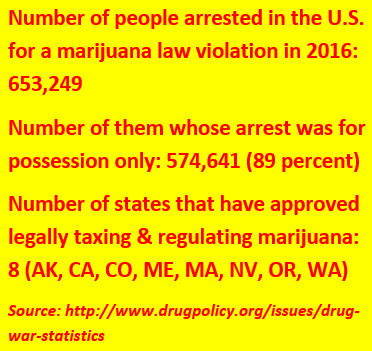

Although you wouldn’t know it, thanks to a near-century of Washington scare tactics, smokeable marijuana is one of the world’s most benign inebriants. As Lynn Zimmer, a sociologist at Queens College, and John P. Morgan, a professor of pharmacology at the City University of New York, showed twenty years ago in “

Although you wouldn’t know it, thanks to a near-century of Washington scare tactics, smokeable marijuana is one of the world’s most benign inebriants. As Lynn Zimmer, a sociologist at Queens College, and John P. Morgan, a professor of pharmacology at the City University of New York, showed twenty years ago in “

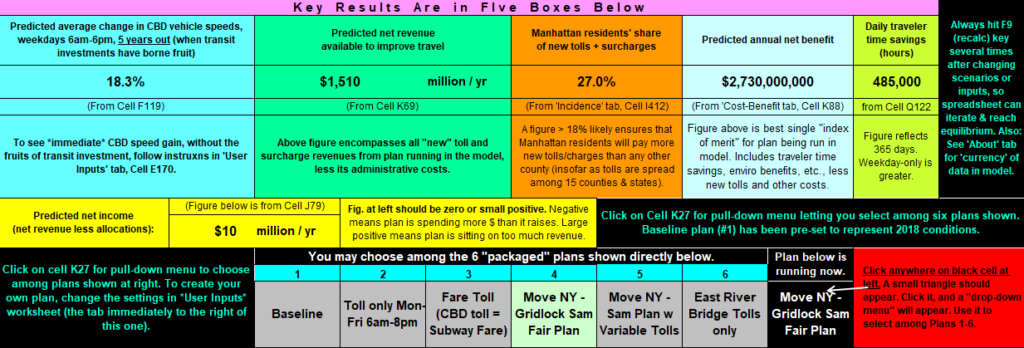

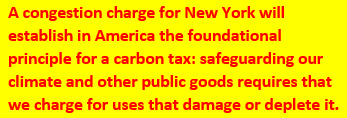

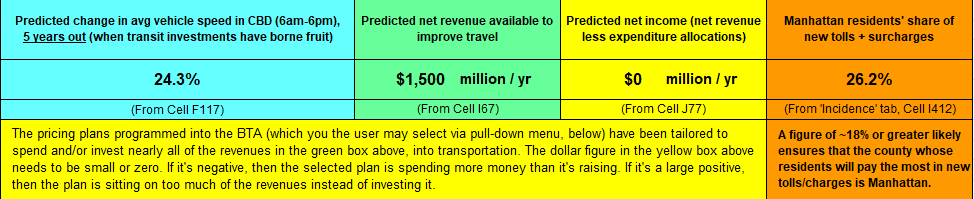

Congestion pricing levies fees on vehicle travel into or within the core of a city. Singapore,

Congestion pricing levies fees on vehicle travel into or within the core of a city. Singapore,

The trope

The trope  Lifton, a psychiatrist who turned 90 last year, has long observed, lived among and written about the perpetrators and victims of some of the 20th Century’s most profound atrocities — the atomic bombings of Japan, the Vietnam War and, of course, the Nazi Holocaust. His writing humanizing the

Lifton, a psychiatrist who turned 90 last year, has long observed, lived among and written about the perpetrators and victims of some of the 20th Century’s most profound atrocities — the atomic bombings of Japan, the Vietnam War and, of course, the Nazi Holocaust. His writing humanizing the

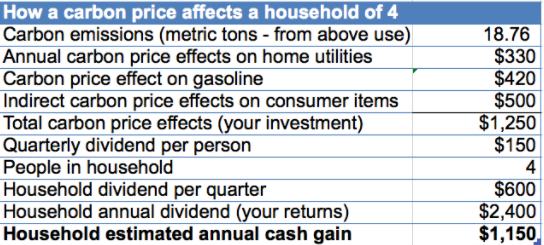

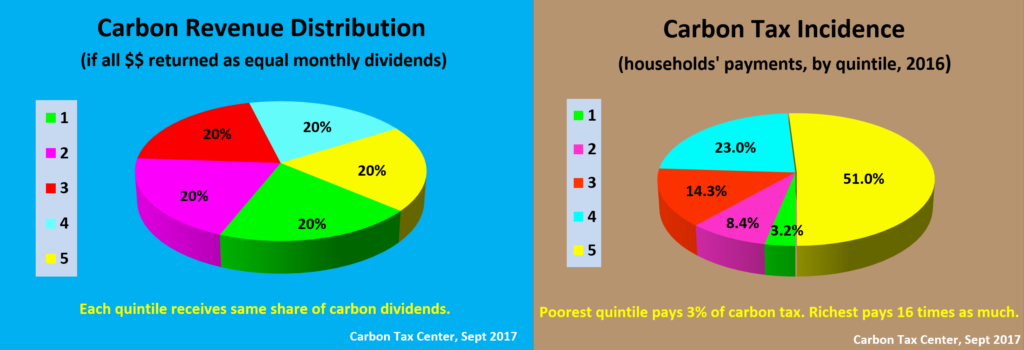

These disparities underlay Bernie Sanders’ “political revolution” campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination last year. And they added fuel to the sense of white grievance that energized Donald Trump’s successful run for the presidency. They also bolster the case for “carbon dividends” — the idea of distributing all or nearly all carbon tax revenues equally to U.S. households popularized as carbon fee and dividend by the non-partisan

These disparities underlay Bernie Sanders’ “political revolution” campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination last year. And they added fuel to the sense of white grievance that energized Donald Trump’s successful run for the presidency. They also bolster the case for “carbon dividends” — the idea of distributing all or nearly all carbon tax revenues equally to U.S. households popularized as carbon fee and dividend by the non-partisan  The progenitors of CLC’s carbon dividend plan, James Baker and George Shultz, are “exemplars of the outcast center-right GOP establishment,” as I described them recently in the

The progenitors of CLC’s carbon dividend plan, James Baker and George Shultz, are “exemplars of the outcast center-right GOP establishment,” as I described them recently in the