This guest post is by Philip H. Kahn, Co-Leader of Citizens’ Climate Lobby’s New York City Chapter.

A new report commissioned jointly by the operator and regulator of the New York State power grid has found that a $40 per ton charge on CO2 emitted in generating electricity sold in the state would have an insignificant impact on electricity costs, provided the carbon revenues are redistributed to electricity customers in the form of bill reductions.

Problem statement from Brattle report. Solution: $40/ton charge on CO2 from electricity generation, with revenues returned to ratepayers.

The report, with the unwieldy title, Pricing Carbon into NYISO’s Wholesale Energy Market to Support New York’s Decarbonization Goals, was prepared by the Brattle Group for the NY Independent System Operator (NYISO) and the state’s Public Service Commission. Its key finding — that monthly electric bills would likely rise no more than 2 percent and might even fall slightly (by 1 percent) — flies in the face of the conventional wisdom that carbon charges necessarily drive electric rates higher.

Half of the upward cost pressure from the carbon charge would be offset by returning carbon revenues to customers. The remainder would be alleviated through three separate but parallel marketplace responses:

- The $40/ton carbon charge will incentivize natural gas generators to upgrade conventional natural gas-powered plants to combined-cycle plants that typically extract 50-60 percent more kilowatt-hours from each unit of fuel.

- The higher market price for wholesale power will encourage development of more renewable (largely wind and solar) power generation to supply the state.

- The carbon charge will, over time, replace the Zero Emission Credits (ZECs) and Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) that now subsidize nuclear and renewable energy generation.

Carbon emissions from statewide electricity generation would fall by 2.6 million tons per year, according to the report, an amount equal to 8 percent of current emissions from the electric sector. “This estimate is probably conservatively low,” says Brattle, “because it does not account for the potential re-dispatch of existing resources, nor does it include innovative responses that the market might elicit but that we have not imagined.”

The Brattle researchers assumed that all of the revenue raised from the carbon charge would be returned to customers as line items reducing monthly bills. Alternative revenue treatments that direct some of the funds to energy efficiency and clean energy programs operated by the NY State Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA) would result in deeper carbon cuts but at the possible expense of somewhat higher electric bills. This approach is supported by the Natural Resources Defense Council, the renowned environmental law group whose advocacy has led to utility and state government funding of end-use efficiency and renewables.

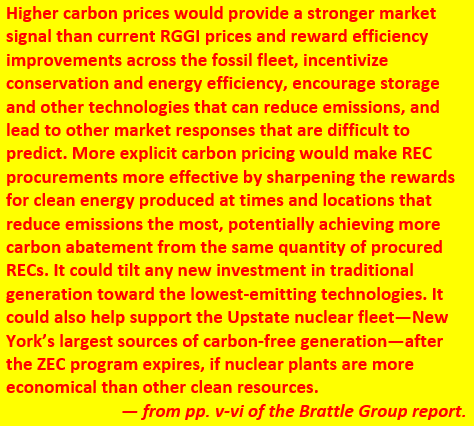

How the proposed carbon charge can cut CO2 emissions from NY State’s electricity sector.

The Brattle report pegged its proposed carbon charge to the “social cost of carbon,” which the U.S. Interagency Working Group on the Social Cost of Carbon last year specified at $43/ton of CO2 and rising over time. A combined carbon price of $40/ton from the carbon charge and the anticipated “market” price of $17/ton in 2025 in response to the tightening cap set by the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, or RGGI, would total the $57/ton Social Cost of Carbon in that year.

The Brattle Group’s recommendation of a substantial, explicit carbon charge differs from the state carbon pricing bills under consideration in Massachusetts. Both MA H1726 (the state’s house bill) and S1821 (the senate bill) exempt electricity, with the rationale that carbon emissions from power generation in Massachusetts and the other Northeast states (except New Jersey) are already priced under RGGI. The $57/ton charge that Brattle recommends for New York State in 2025 would be more than triple the RGGI-alone price in that year.

Variations of the Brattle approach may be usable in other wholesale energy markets, especially those that are coterminous with a single state, such as Texas and California, and that use RECs to subsidize renewable energy. What makes New York’s case particularly promising is that the subsidies now provided by the ZECs and RECs would be reduced because non-fossil fuel generation would receive the same market price set by fossil generators subject to the carbon adder.

Fig. 1 from Brattle report. Note concerted drop in emissions from electricity.

If the carbon adder fee paid by the fossil-fuel generators is returned to the ratepayers then rates will not go up. Other ISOs with RECs in their markets could implement a similar scheme, but multi-state ISO markets would require negotiations between states with different REC regimes.

Implementation of the Brattle Group’s recommended carbon charge would give NY Gov. Andrew Cuomo a way out of his unpopular new program subsidizing several upstate nuclear power plants via Zero Emission Credits pegged to the Social Cost of Carbon. That program, which went into effect in April, adds a charge to all state customers’ monthly electric bills which flows to Entergy Corp., the reactors’ owner-operator.

Proponents laud the nuclear subsidy for monetizing the reactors’ zero carbon emissions and helping NY State meet carbon-reduction targets, but opponents point to the anticipated $7 billion price tag over the dozen years of the subsidy, as well as the lack of equivalent support for energy efficiency and other zero- or low-carbon electricity provision. A universal carbon charge such as the $40/ton fee recommended by Brattle would reduce the nuclear-only subsidy while retaining the monetary reward that could enable the reactors to continue operating. As the carbon adder is increased, the subsidies would diminish, ultimately to zero.

Here’s what’s new:

Here’s what’s new:

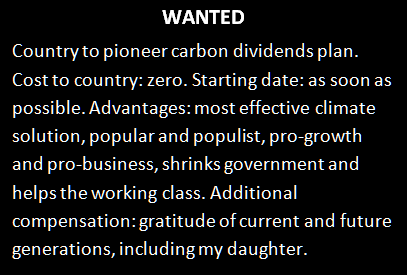

Next is the geopolitical barrier. Under the current rules of global trade, countries have a strong incentive to free-ride off the emissions reductions of other nations, instead of strengthening their own programs.

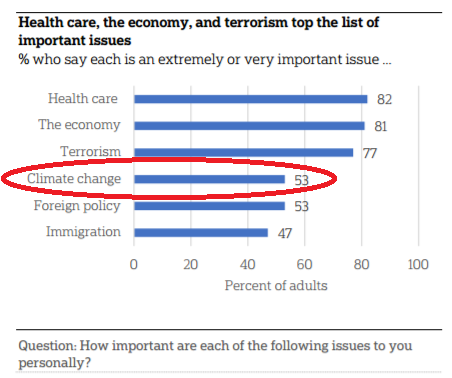

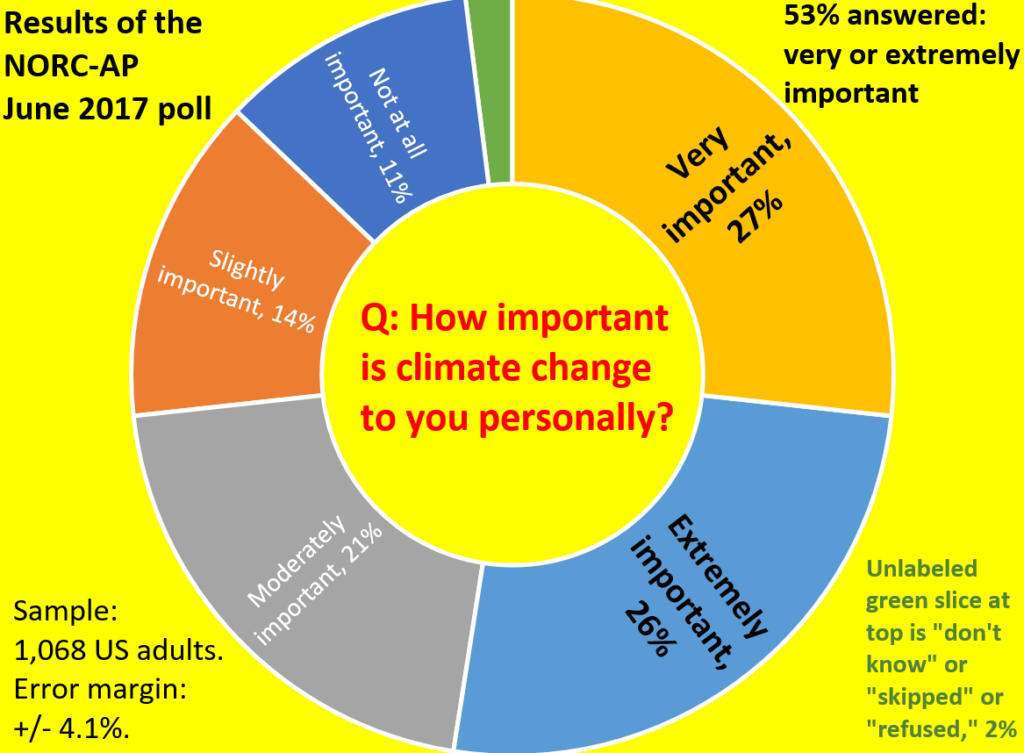

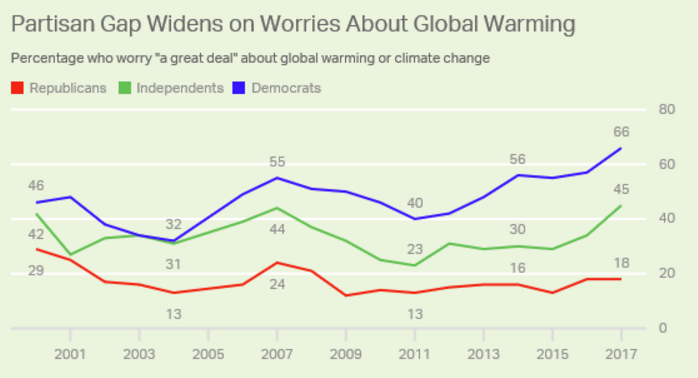

Next is the geopolitical barrier. Under the current rules of global trade, countries have a strong incentive to free-ride off the emissions reductions of other nations, instead of strengthening their own programs. According to the US Treasury Department, the bottom 70 percent of Americans would receive more in dividends than they would pay in increased energy prices. That means 223 million Americans would win economically from solving climate change. And that is revolutionary, and could fundamentally alter climate politics.

According to the US Treasury Department, the bottom 70 percent of Americans would receive more in dividends than they would pay in increased energy prices. That means 223 million Americans would win economically from solving climate change. And that is revolutionary, and could fundamentally alter climate politics. Let’s take China as an example. China is committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but what its leaders care even more about is transitioning their economy to consumer-led economic development. Well, nothing could do more to hasten that transition than giving every Chinese citizen a monthly dividend. In fact, this is the only policy solution that would enable China to meet its environmental and economic goals at the same time.

Let’s take China as an example. China is committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but what its leaders care even more about is transitioning their economy to consumer-led economic development. Well, nothing could do more to hasten that transition than giving every Chinese citizen a monthly dividend. In fact, this is the only policy solution that would enable China to meet its environmental and economic goals at the same time.

Our long-building climate crisis is already materializing as drowned coasts, punishing droughts, vanishing glaciers—and political upheaval. At its root is a century-old lie: market prices for gasoline and other fossil fuels that do not factor in the damage from burning them.

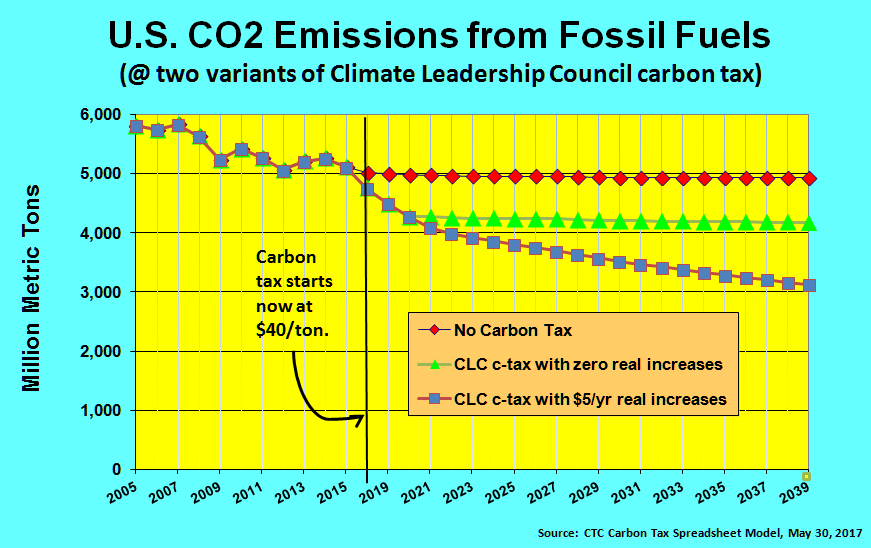

Our long-building climate crisis is already materializing as drowned coasts, punishing droughts, vanishing glaciers—and political upheaval. At its root is a century-old lie: market prices for gasoline and other fossil fuels that do not factor in the damage from burning them. But government policy revolves around trade-offs, and on balance the Council’s carbon tax is worth supporting. After all, well over 80 percent of the Clean Power Plan’s targeted reductions for 2030

But government policy revolves around trade-offs, and on balance the Council’s carbon tax is worth supporting. After all, well over 80 percent of the Clean Power Plan’s targeted reductions for 2030