For Immediate Release:

December 12, 2015

Prominent Climate Policy Analysts React to Paris Climate Agreement

Science and economics experts applaud the agreement and point to the next step: taxing carbon pollution

Today negotiators from 195 countries came to a landmark agreement that commits nations to a plan to decrease greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change. The Carbon Tax Center, a leading U.S. advocacy group that organized a letter to the Paris negotiators signed by 32 experts including 4 Nobel prize winners, applauds the Paris agreement, while urging governments to adopt national carbon taxes to achieve the ambitious goals in the new agreement.

Carbon Tax Center director Charles Komanoff said, “Now that all nations have committed to reducing emissions, the next step is for each and all to enact and implement transparent and robustly-rising carbon taxes. No other measure can both harmonize individual policies into global ones and scale up renewables and energy efficiency fast enough to avert the worst catastrophic scenarios.”

Two notable signers of the letter also reacted to the historic agreement:

“Today’s UN agreement shows laudable global concern and ambition to confront the climate challenge. A clear next step is for nations to enact broad, persistent and rising prices on carbon pollution to catalyze efficiency, low-carbon energy investment and innovation,” said former Secretary of Labor, Robert Reich.

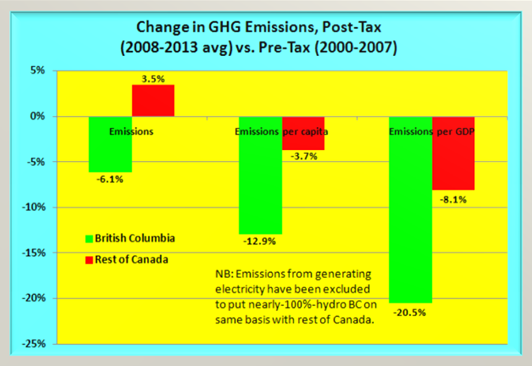

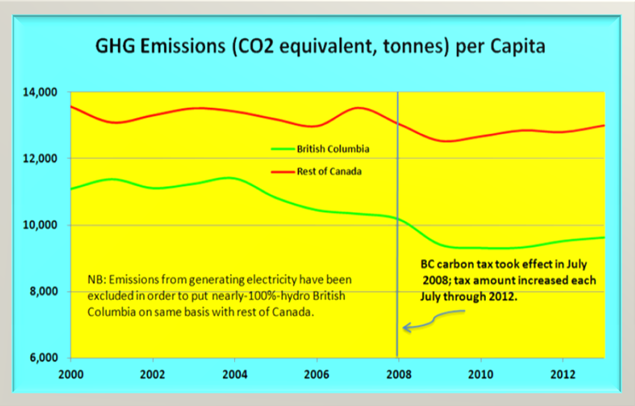

Renowned Harvard Economics professor Martin Weitzman agreed, adding, “British Columbia’s popular revenue-neutral carbon tax offers a very good starting point.”

Other signers of the letter organized by the Carbon Tax Center include Steven Chu, Nobel Prize-winning physicist and President Obama’s first Secretary of Energy; George P. Shultz, President Nixon’s Secretary of Labor and President Reagan’s Secretary of State; Nobel Prize-winning economists Joseph Stiglitz, Thomas Schelling and Kenneth Arrow; founding Congressional Budget Office DirectorAlice Rivlin; Greg Mankiw, chair of President George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers; and Jerry Taylor, president of the Niskanen Center.

View the letter and a complete list of signers here: https://www.carbontax.org/

The Carbon Tax Center is encouraged by the global momentum emerging from the Paris talks and will continue its work educating policy makers and the public about the need for carbon taxes and the political path that will make them possible.

###

The Carbon Tax Center launched in January 2007 to give voice to Americans who believe that taxing emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases is imperative to combat global warming. CTC is a clearinghouse for research, analysis and advocacy to establish a carbon tax as the centerpiece of U.S. policy to combat catastrophic climate change. It has been the leading NGO advocating for carbon taxing as the key to unlocking low- and non-carbon investment and innovation to drive the global energy system away from fossil fuels to renewable wind, sunlight and efficiency.