The Yale climate economist William Nordhaus goes after Pope Francis in the current New York Review of Books on the question of how best to prevent global warming. But after landing a few solid punches, he collapses in a muddle all his own by obscuring the difference between carbon taxes and cap-and-trade.

Nordhaus zeroes in a number of passages in “On Care for Our Common Home,” the recent papal encyclical dealing with global warming, that, to his mind, show remarkable ignorance about the workings of modern economics. One passage calls on society “to reject a magical conception of the market, which would suggest that problems can be solved simply by an increase in the profits of companies or individuals,”while another takes aim at the profit motive:

The principle of the maximization of profits, frequently isolated from other considerations, reflects a misunderstanding of the very concept of the economy. As long as production is increased, little concern is given to whether it is the cost of future resources or the health of the environment; as long as the clearing of a forest increases production, no one calculates the losses entailed in the desertification of the land, the harm done to biodiversity or the increased pollution. In a word, businesses profit by calculating and paying only a fraction of the costs involved. ¶195.

To be sure, resource losses are chronically under-estimated. But Nordhaus maintains that the pope misses an important point, which is that the problem is not markets per se, but markets that are poorly designed and hence encourage the wrong kinds of activity.

“Markets can work miracles when they work properly,”Nordhaus writes, “but that power can be subverted and do the economic equivalent of the devil’s work when price signals are distorted.” The best way to correct such distortions is to see to it that social costs, or “externalities,” are incorporated in the price of a particular commodity or action. Only when economic actors are required to bear the full burden will they then find it profitable to seek out alternatives that are cheaper and cleaner. Otherwise, society finds itself in the strange position of subsidizing waste by allowing manufacturers to emit greenhouse gases and the like for free. As Nordhaus puts it:

Putting a low price on valuable environmental resources is a phenomenon that pervades modern society. Agricultural water is not scarce in California; it is underpriced. Flights are stacked up on runways because takeoffs and landings are underpriced. People wait for hours in traffic jams because road use is underpriced. People die premature deaths from small sulfur particles in the air because air pollution is underpriced. And the most perilous of all environmental problems, climate change, is taking place because virtually every country puts a price of zero on carbon dioxide emissions.

Nordhaus might have mentioned the entrenched political structures that foster such under-pricing in the first place. But let’s not quibble: his logic thus far is impeccable. He then goes off the rails, however, over a passage in the encyclical dealing with carbon-emission permits. According to the pope:

The strategy of buying and selling “carbon credits” can lead to a new form of speculation which would not help reduce the emission of polluting gases worldwide. This system seems to provide a quick and easy solution under the guise of a certain commitment to the environment, but in no way does it allow for the radical change which present circumstances require. Rather, it may simply become a ploy which permits maintaining the excessive consumption of some countries and sectors. ¶171.

Although Francis is probably talking about cap-and-trade, Nordhaus is not so sure since “carbon credits” is not a term that practitioners usually employ with regard to the trade in carbon emissions. So he argues that “this part of the encyclical is clearly a critique of market-based environmental approaches”— all such approaches, that is — a category that in his view includes both cap-and-trade and carbon taxes.

This leads to a fatal error: defending both without delineating the differences between the two. Nordhaus has argued in favor of carbon taxes in the past, and he concedes in his NYR article that such an approach “is simpler and avoids any of the potential corruption, market volatility, and distributional issues that might arise with cap-and-trade systems.” But since carbon taxing also fiddles with markets, he concludes: “It is unfortunate that he [the pope] does not endorse a market-based solution, particularly carbon pricing, as the only practical policy tool we have to bend down the dangerous curves of climate change and the damages they cause.”

Wrong. Cap-and-trade clearly is a market-based solution because it creates new arenas for the buying and selling of emission permits, complete with futures markets and financial derivatives. But a carbon tax is not. Instead of creating new ways of buying and selling, taxing carbon is a form of direct behavior modification not unlike a traffic fine or a golf-course fee. Instead of encouraging speculation, it does the opposite by making it crystal clear that economic actors will have to pay a set premium for every unit of carbon dioxide they emit.

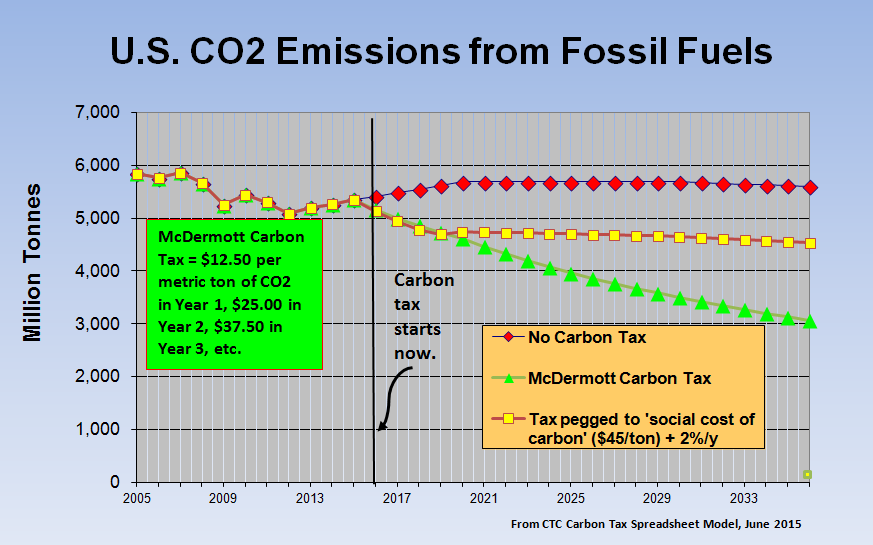

So while the pope may have gotten a good deal wrong, this is one thing he gets right. Not only does cap-and-trade promote speculation, but Francis is correct in pointing out that, in practice, it has done little to reduce emissions or encourage fundamental technological change. Setting a strict limit on greenhouse gases and then allowing investors to bid on emissions rights up to a certain level is music to the ears of neo-liberal economists for whom there can never be enough markets. But implementing such a program has proved a nightmare.

Due to heavy lobbying by corporations and politicians, the EU’s Emissions Trading System, the largest carbon market in the world, exempts 55 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, according to the Greek economist Andriana Vlachou. Since the system leaves it to individual member states to estimate their emissions, over-reporting has been rife. Offsets, the practice of allowing member states to reap credits by sponsoring carbon-capture projects such as new forests, have been especially problematic. As the Carbon Tax Center’s James Handley has pointed out, estimating savings from such projects is difficult, while verifying that developers are telling the truth about the benefits is even worse. Volatility is another problem. After the EU allocated too many permits, prices plunged so low in 2013 that officials had to take 900 million permits off the market. Since trading is electronic, hackers have meanwhile made off with millions.

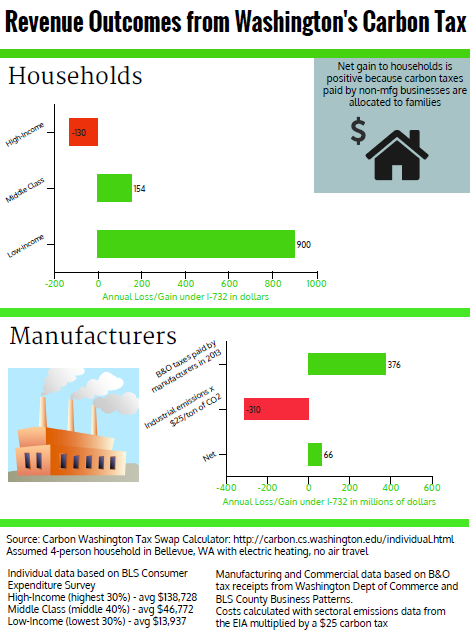

It’s the sort of system that only a free-market Chicago economist could love – and, given the opportunities for corruption, maybe an old-school Chicago politician as well. By comparison, a carbon tax is the essence of simplicity. Administrative costs, which involve little more than calculating the carbon content of a given fossil fuel and then levying a charge “upstream,” are minimal. So are enforcement costs. There are no offsets, no complicated negotiations to determine each nation’s emissions quota, no wrestling with entrenched political interests to determine which industries are covered and which are not. While Vlachou reports the EU’s cap-and-trade program weighs especially heavily on poor electricity users, such consequences can be easily mitigated in the case of a carbon tax by earmarking revenues for social programs, investment in poor neighborhoods, or reducing income taxes for lower earners.

Nordhaus is not the only one to blur the difference between a carbon tax and tax-and-trade. Cass R. Sunstein, the Harvard law professor and recent Obama operative, recently made the same blunder in a column defending not only markets but consumerism and economists in general, who, he assures us, are “excellent technicians” and “pretty decent moralists” as well. The pope is not the only one who finds this difficult to swallow. Suspicion of market-based solutions may not be so unjustified after all.