Today’s New York Times turned over a patch of its most coveted space — on its op-ed page — to a curious essay. On Carbon, Tax and Don’t Spend is vexing and even a tad bipolar, in one moment calling a carbon tax "glamorous" (who knew?), but in the next insinuating that a revenue-neutral carbon tax could be a big no-no for the U.S.

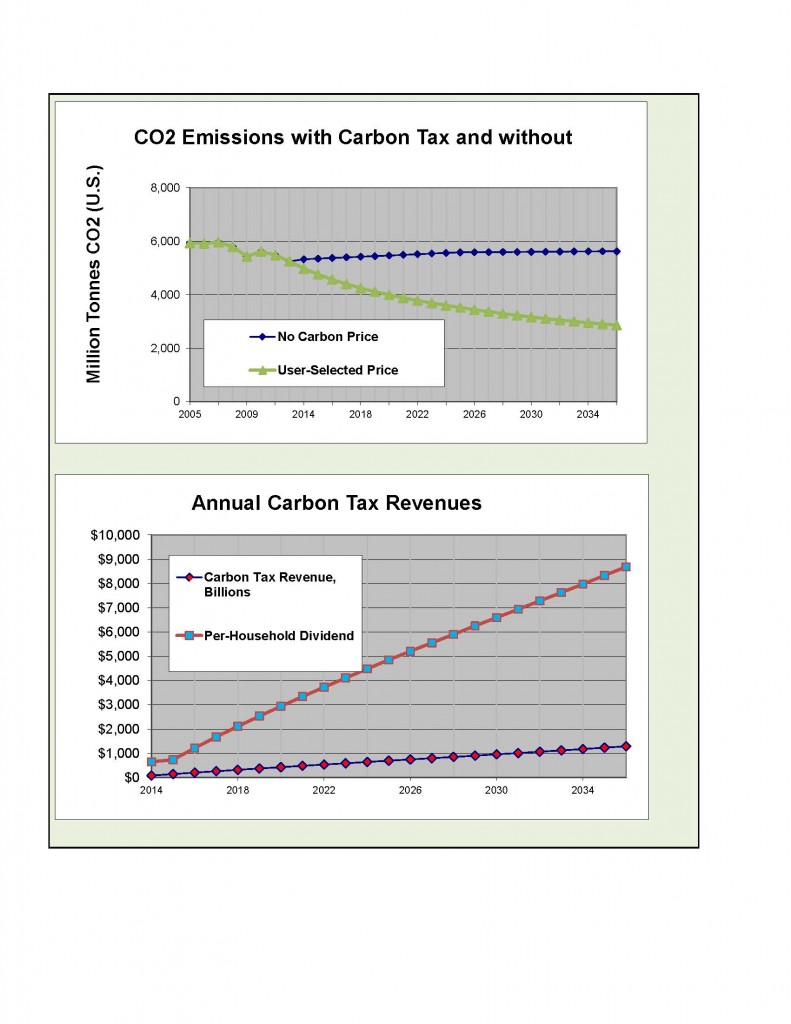

The article’s big idea is that carbon tax revenues should be allocated to industry as lump-sum incentives to invest in cutting carbon, rather than returned to households to offset higher prices for energy and products. To support this thesis, the author points to carbon-taxing Scandinavia, where Denmark, the only country to dedicate carbon tax revenues to industry, is also the only one where CO2 emissions have plummeted.

On close examination, this "finding" turns flimsy. The fly in the ointment is that while all four Scandinavian countries have indeed levied some form of carbon tax since the early 1990s, in each case the tax levels so far have been on the "lite" side, making it difficult to tie changes in emissions to specific tax and revenue policies.

On close examination, this "finding" turns flimsy. The fly in the ointment is that while all four Scandinavian countries have indeed levied some form of carbon tax since the early 1990s, in each case the tax levels so far have been on the "lite" side, making it difficult to tie changes in emissions to specific tax and revenue policies.

Sweden, for example, taxes carbon at $150 per ton (that’s a hefty $41 per ton of carbon dioxide), as we report elsewhere on this site, but fuels to generate electricity are untaxed, and industries pay only 50%. Denmark’s carbon tax is $14 per ton of CO2, reports Alan Durning of Sightline Institute; while that’s not chicken feed — it equates to around half-a-buck per gallon of gasoline — it’s still insufficient to account for more than a fraction of Denmark’s carbon reductions, especially considering that, as in Sweden, industry in Denmark is taxed at only half the going rate.

Denmark has trimmed CO2 emissions impressively. The Times op-ed puts the drop in per-capita emissions at 15% from 1990 to 2005; using regression analysis, which infers the trend line from all the annual data points instead of just the first and last, we calculated the per-capita drop at 15% using EIA data and 18% using CDIAC data. This decline is heartening, but we’re inclined to ascribe it primarily to Denmark’s aggressive pursuit of wind power (which now accounts for over 20% of electricity generation), steep taxes on coal-fired electricity (not quite a carbon tax though with similar impact) and ongoing promotion and enabling of bicycle transportation, which now accounts for 24% of urban trips by vehicle, nationwide.

Our big beef with the article is with its use of Norway as a lesson in failed carbon taxing. Unlike Denmark, Norway doesn’t dedicate carbon tax revenues to industry, and per capita emissions have risen 43%. Ergo, implies the author, carbon taxing with revenue return is tantamount to allowing producers

"to continue polluting while handing over cash to the government." Not only is that argument a non sequitur, its premise may be shaky if Norway’s carbon accounting hasn’t been adjusted for oil infrastructure and exports, which have grown enough recently to make Norway the world’s third largest oil exporter.

We’ll concede that countries with sturdy safety nets and small carbon taxes can probably get away with directing the tax revenues to industry or other agents for low-carbon investment. But for big carbon taxes in the USA, we think a revenue-neutral tax with revenue recycling will be imperative to keep not only poorer Americans but much of the middle class from being pushed to the wall.

Notwithstanding our dissatisfaction with the op-ed, we regard the author, Monica Prasad of Northwestern University, as an interesting thinker. Her new paper on which she based her essay, Taxation as a Regulatory Tool: Lessons from Environmental Taxes in Europe, is a provocative work that uses behavioral economics as a window for evaluating taxes and other policies for curbing carbon emissions. It’s worth careful study, by us and by you.

Photo: Flickr / Less Salty.