No U.S. state has a carbon tax. This fall, carbon tax proponents in the state of Washington are seeking to break through with Initiative-1631, a state tax on carbon emissions, which you can read about here. For a deep dive into the factors that defeated Washington’s 2016 carbon-tax ballot initiative I-732, click here.

Washington and 7 other states (including Washington DC, which we refer to here as a state) were deemed “promising” arenas for enacting state carbon taxes, in a comprehensive 2017 report by the Carbon Tax Center.

Another page, The Other 49 States, looks at state carbon tax organizing in a half-dozen other states.

CTC Report Ranks the States on Carbon Tax Potential

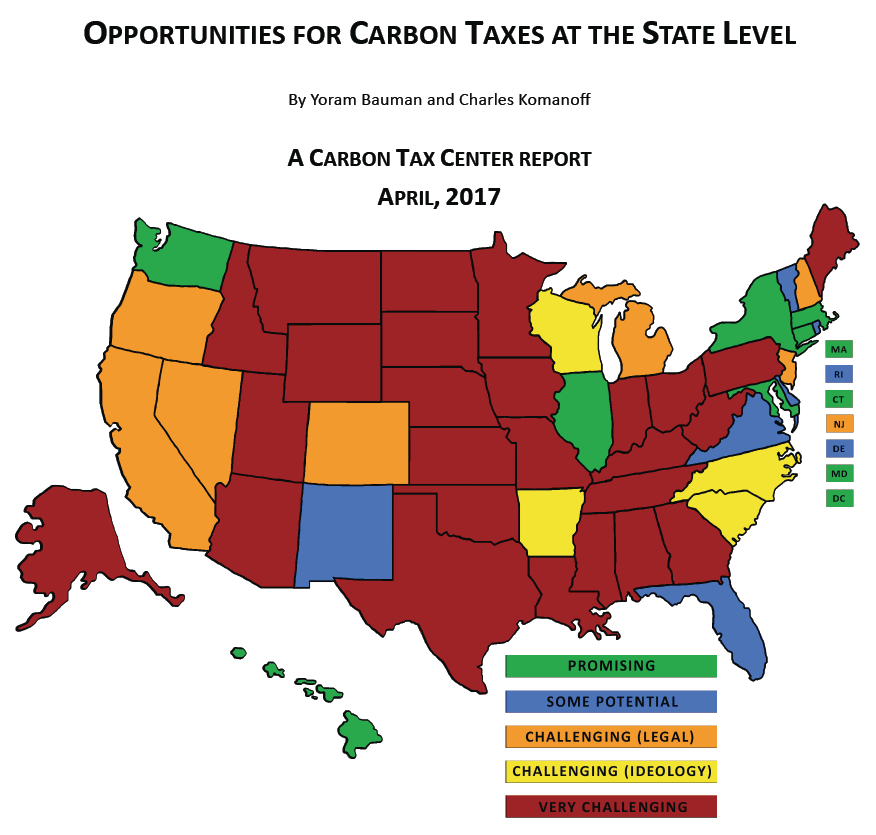

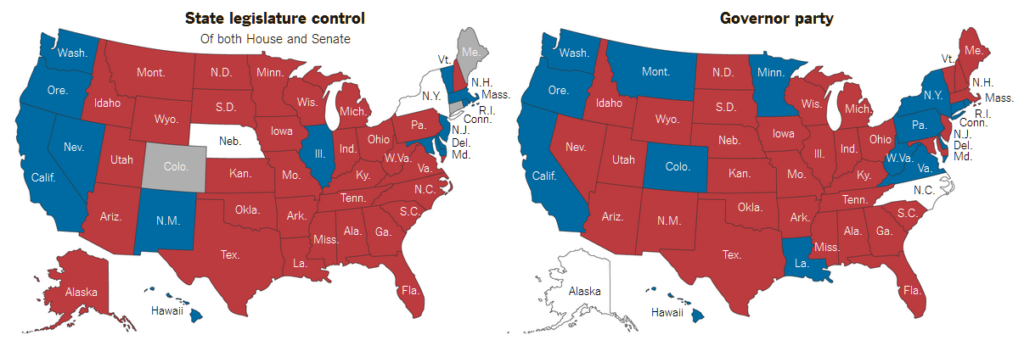

The report was written by Yoram Bauman, who spearheaded a Washington state carbon tax effort in 2016, and Carbon Tax Center director Charles Komanoff. It classifies the 51 states into five categories of carbon tax readiness ranging from “promising” to “very challenging.” (See map.)

Cover page of CTC’s new report rating the states’ carbon tax potential.

As the map shows, the eight most promising states are Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Washington and the District of Columbia. (Follow these links for historical perspective and other information on Massachusetts, New York, and Washington that isn’t in the report.) We rate another 17 states as having “potential” for enacting state carbon taxes, with some having relatively clear paths while others appear to face legal or ideological constraints. (Follow these links for additional information on Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and—as a bonus—the city of Boulder, Colorado.)

The other 26 states are a lot less promising. Our report explains why.

The rankings are just one aspect of the report. Each state gets an overview, a brief analysis of CO2 emissions, summaries of local climate impacts and current climate policies, a sketch of carbon pricing activism, a brief look at climate ideology and politics, recent polling results, and, where applicable, a summary of ballot measures and proposed legislation.

The report is comprehensive in its coverage but concise in each state’s analysis and ranking. It clocks in at 120 pages but it’s well worth perusing for info on your state and how it stacks up with others. Click here (2 MB pdf) to download. (A higher-res pdf is also available, click here (14 MB).)

Further below is extensive coverage of the Washington state I-732 campaign and its aftermath, along with info on carbon tax organizing in five other states as well as Boulder, CO’s carbon tax on electricity generation. Click on those links and read our introduction for context.

Also see our August 2016 post reporting on the new Brookings Institution report, State-Level Carbon Taxes: Options And Opportunities For Policymakers. It’s essential reading for people seeking to advance carbon taxes at the state level and anyone who wants to understand the nuts and bolts of designing and implementing actual carbon taxes.

State Carbon Taxes: Overview

“It is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.” — Justice Louis D. Brandeis (New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, dissenting opinion, 1932)

This page covers organizing campaigns for U.S. carbon taxing at the state level, with sections on Washington State, Oregon, New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Vermont.

With a national carbon tax blocked by the denialist Republican majority in Congress and a carbon-besotted White House, a growing number of climate advocates are heeding Justice Brandeis’s advice and are organizing at the state level. “Retail” politics, it is thought, might assuage concerns over outside-the-box ideas like carbon taxing, perhaps as occurred in the successful push for marriage equality (the right to same-sex marriage) which began and spread as state-level campaigns.

With a national carbon tax blocked by the denialist Republican majority in Congress and a carbon-besotted White House, a growing number of climate advocates are heeding Justice Brandeis’s advice and are organizing at the state level. “Retail” politics, it is thought, might assuage concerns over outside-the-box ideas like carbon taxing, perhaps as occurred in the successful push for marriage equality (the right to same-sex marriage) which began and spread as state-level campaigns.

Moreover, progressive and popular options for distributing carbon tax revenues can be made more tangible at the state level than the federal. This point was underscored by a Jan. 2015 study by the Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy ranking the 50 states on their tax incidence that established that states are more regressive taxers than the federal government. In particular, sales taxes could be swapped out for carbon taxes, as advocates in Washington State proposed in their I-732 ballot initiative in 2016 (full discussion further below).

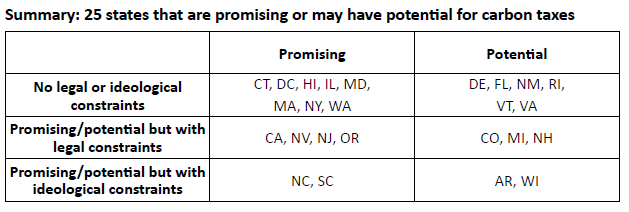

Not all states are riven by ideological resistance. While America’s geographical diversity can impede national unity, it has left some states less beholden to fossil fuel interests. Naturally, advocates are focusing on those states. (In March 2016, Resources for the Future posted two superb summaries of proposals in six states to adopt carbon taxes; the first focused on the tax rates (see graphic below), while the second addressed revenue treatment and household “incidence.”)

Graph courtesy of RFF. See link in adjoining paragraph.

States have also pushed the envelope on issues like minimum wage and fuel-efficiency standards, moving the national discussion as they did so. In a 2016 op-ed in the New York Times, Georgetown University law professor David Cole ascribed the National Rifle Association’s success at strangling national gun-control regulations to a decades-long campaign that changed state constitutions and laws to protect the right to possess and carry guns. Less far afield is the fact that gasoline taxes first took root in a handful of Western states to fund road construction, before spreading to the rest of the country. State carbon taxes could, it is hoped, create a similar template leading eventually to federal enactment.

The EPA Clean Power Plan may have provided an opening for state carbon taxes through a provision allowing states to submit projected emission reductions from carbon taxes applied to power generation (unfortunately, reductions from carbon-taxing non-electric sectors such as transportation would not receive credit). A June 2015 report from the Niskanen Center concluded that even small state carbon taxes could effectuate the required emissions reductions in most cases, mirroring our own modeling results on the national level.

Still, state carbon taxing raises issues that don’t apply to a federal tax. State policy makers and advocates need to address these concerns:

- Competitiveness: It would be hard for any one state to push its carbon tax too high, due to concerns over competitive advantage and inter-state “leakage” (e.g. driving out-of-state to fill up with untaxed gasoline).

Yet using some carbon tax revenues to reduce business taxes (as was proposed in Washington State) may soften concerns over economic impact. The cross-border issue may be less salient in larger Western states than in smaller East Coast states.

Jeff Renfro, a key member of a team at Northwest Economic Research Center that modeled a possible Oregon carbon tax, said:

We tried [in our modeling] to wreck the economy. We modeled a big tax – $100 a ton – with a relatively short phase-in period, and we assumed the government put the revenues toward non-productive reserves. Even in that scenario, we were surprised by how small the effects on employment were relative to the overall economy. (Interview with CTC researcher Matt Gordon, July 10, 2015)

- Efficiency: Energy policy is largely determined at the federal level. Administrative costs could be disproportionately higher for state taxes, due to greater cross-border movements of electricity and fuels among states than between the U.S. and other nations. In some states, utility sector regulation may complicate efforts to tax fossil fuels sufficiently upstream.

Many states already have taxes on gas and electricity, however, and it shouldn’t be difficult to piggyback a carbon tax on those taxes without significantly increasing administrative burdens. British Columbia’s carbon tax program uses this technique, and reports the administrative burden as negligible.

- Coverage: Only a national carbon tax will enable the U.S. to impose Border Adjustment Taxes to induce China and other countries to adopt their own taxes, which is a key benefit of pursuing carbon taxing. States cannot pursue a similar strategy without violating the commerce clause of the Constitution.

Although states may not tax imported goods, that prohibition shouldn’t be construed to mean they can’t tax imported electricity or fossil fuels that are then used within the state. In fact, some advocates see this as an opportunity for economic development; carbon-taxing out-of-state fossil-based electricity and fuels could stimulate growth in local renewables and energy-efficiency industries.

- Local Policy: Every state has idiosyncracies. In Oregon, the constitution mandates that all revenues from taxing gasoline must be deposited in the Highway Trust Fund. In Washington, state law precluded carbon tax revenues from being used for dividends to the public. Yet this patchwork of state policies may be a motivating factor in driving a national policy. The complications of doing business in jurisdictions with varying policies have even driven some oil companies to demand more unified action on climate change.

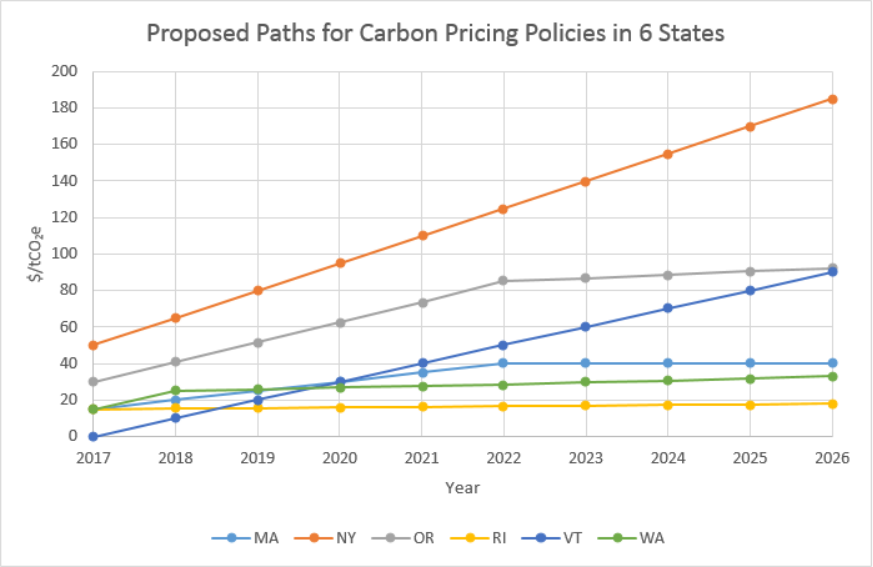

That said, the 2016 elections further cemented the Denier (Republican) Party’s hold on state governments, as the New York Times graphic below illustrates.

Republicans hold control of the governor’s office and the legislature in 24 states, while Democrats have that status in only six, according to this New York Times graphic.

On the other hand, red states tend to be fossil fuel-dominated states already out of reach of state carbon-tax campaigns. Two states with past or present carbon tax organizing, WA and OR, have Democratic governors and legislatures. Two others, NY and CO, have Democratic governors but divided or uncertain legislatures. Massachusetts and Vermont have Democratic legislatures but Republican governors.