Canada’s Federal Carbon Pricing Program

Unless noted, tax rates on this page are in Canadian dollars and metric tons. Multiply by 0.68 to convert to U.S. short-ton terms, based on the 0.75 January 2023 U.S.-Canada exchange rate.

Canada first implemented a carbon pricing scheme in 2016 with the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, a federal program taxing emissions in a bid to aggressively pursue the country’s Paris climate goals.

Passage of the country’s Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act in 2018 authorized Canada to implement a national carbon price, which we describe below. As of March 2021, that price stood at CA$30 per metric ton (“tonne”) of CO2 equivalent. Factoring in the 0.80 Canada-U.S. dollar exchange rate at that time and the 0.907 weight ratio between a U.S. “short” ton and a metric ton, that tax level equated to a little under $22 (US) per short ton.

The tax rate was raised to CA$50 per tonne in April 2022, and to CA$65 per tonne of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions on January 1, 2023. Annual increases thereafter are intended to bring the tax rate to CA$170 per tonne by 2030. The current (2023) price equates to a bit over $44 (US) per short ton.

Canada’s federal carbon charge operates under the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act (GGPPA), which provides for two main mechanisms:

- A federal fuel charge on fossil fuel distributors, producers, and certain users.

- An output-based pricing system (OBPS) that regulates large industrial emitters.

This hybrid–and complex–pricing system can be seen as an attempt to knit together disparate carbon-pricing sentiments and situations among Canada’s ten provinces and three territories. British Columbia has had a provincial carbon tax since 2008 (see below), while Quebec introduced a carbon cap-and-trade program in 2013. At the other extreme, the UCP government in Alberta, the locus of Canada’s fossil-fuel industry and home of massive, carbon-intensive oil-sands mining, stands adamantly opposed to carbon pricing in any form.

Who Is Subject to the Federal Tax

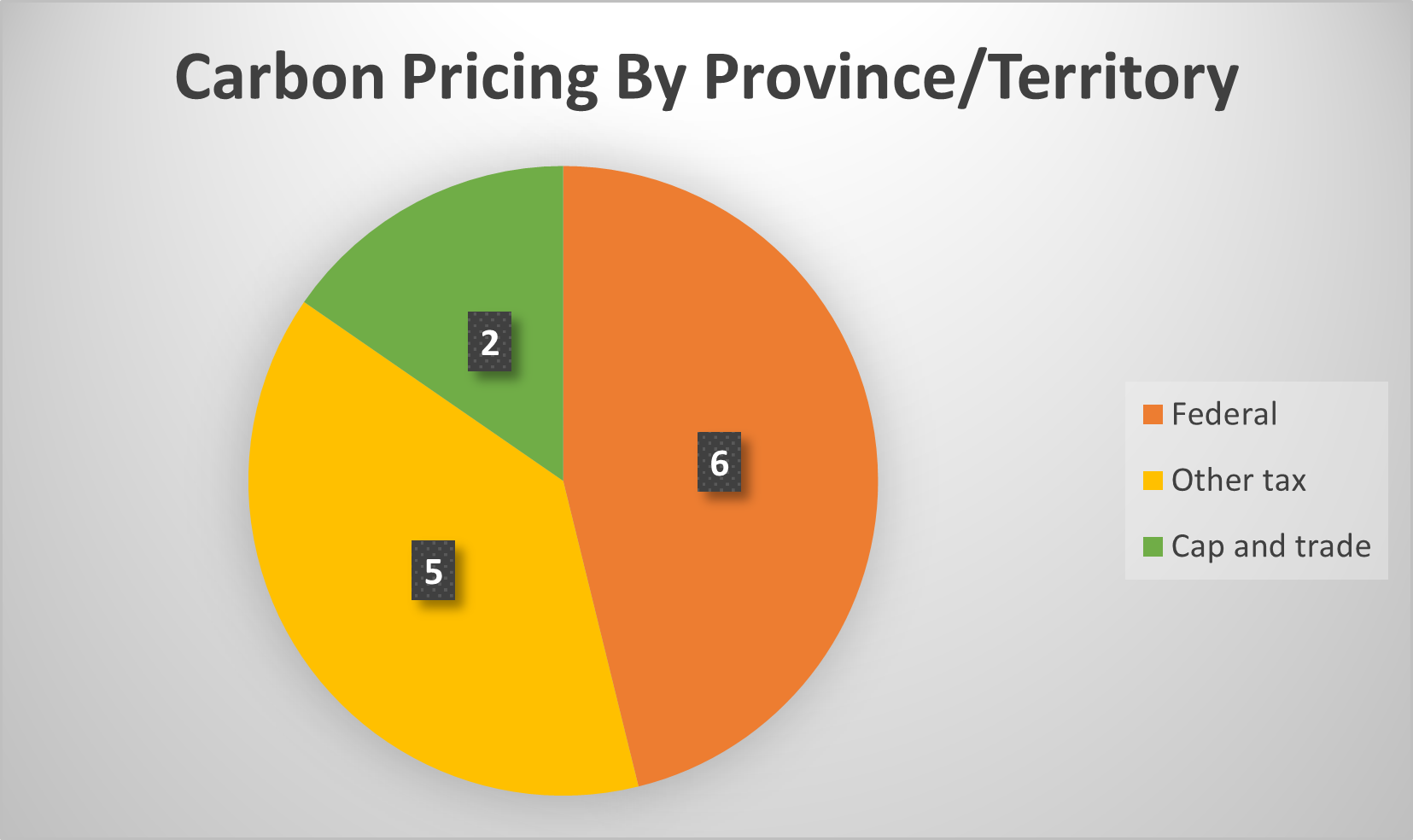

A province or territory that doesn’t create its own strong carbon pricing system is subject to the GGPPA program and must implement both of the above mechanisms.

There are several ways for a territory or province to implement its own program, mainly price-based systems and cap-and-trade schemas. A jurisdiction choosing either system must decrease emissions in line with Canada’s target. Whatever model a province chooses, it is revenue-neutral on the federal level–revenues generated under the system stay in the province or territory where they originate.

1: Federal Fuel Charge

A province that fails to adopt its own strong carbon pricing policy is, by law, subject to the federal fuel charge. As of March 2021, 6 of 13 provinces and territories were using the federal “backstop” fuel charge: Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Nunavut, and Yukon. At the mandated increase rate, the tax was to reach $65/tonne in 2023 — around $44/ton in U.S. terms — which it did, in fact. To support Canada’s pursuit of its Paris goals, the charge will rise rapidly thereafter, reaching $170/tonne in 2030. The stipulated 2023-2030 increase rate averages $15/tonne per year, equivalent to a compound growth rate of 15 percent a year.

| Province/Territory | Carbon Pricing |

| Alberta | Federal |

| British Columbia | BC carbon tax |

| Manitoba | Federal |

| New Brunswick | Output-based pricing system |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Provincial carbon tax |

| Nova Scotia | Cap and trade |

| Ontario | Federal |

| Prince Edward Island | Carbon levy |

| Quebec | Cap and trade |

| Saskatchewan | Federal |

| Northwest Territories | Carbon tax |

| Nunavut | Federal |

| Yukon | Federal |

The fuel charge applies to fuel producers and distributors in backstop jurisdictions that supply any of 21 designated fossil fuels, including diesel, gasoline, and natural gas.

Overall, 90% of revenue raised from the federal fuel charge is to be returned to households in the provinces where the money was collected. In 2020, Parliament’s budget office found that most households in these provinces would get more money back in annual rebates than they paid under the carbon pricing scheme. Between 2022 and 2030, the price of gasoline is projected to rise by 27.6 cents per liter — equivalent to a hefty $1.04 (Canadian) per gallon.

2: Output-Based Pricing System (OBPS)

The GGPPA’s Output-Based Pricing System is intended to put a direct price on industrial carbon pollution without the double exposure from levying the federal fuel charge on them. The OBPS applies in backstop jurisdictions and regulates industrial polluters emitting over 50,000 tons or more of annual greenhouse gas emissions (roughly equivalent to a 6-megawatt coal-fired power plant operating all year at full power). Under the OBPS, these facilities must meet emissions standards by either 1) reducing them outright, 2) paying a carbon tax on excess emissions, or 3) remitting for offset credits or retirement surplus credits.

Carbon Tax: Several provinces, including Quebec and British Columbia, have created their own carbon tax systems to fulfill OBPS.

Remitting for Offset Credits or Retirement Surplus Credits: The offset credit system was just getting started as of March 2021, when the federal government published draft regulations proposing a framework to operate the greenhouse gas offset system contemplated by the GGPPA. With this system, the OBPS creates a financial incentive for energy-inefficient facilities to reduce emissions while encouraging efficient ones to improve. If a facility emits less than its annual limit of carbon dioxide, it earns surplus credits that it can sell to other facilities. If it emits more than its annual limit, it must pay for each extra ton of GHG. For this, a facility has 2 options: 1) pay the carbon price to the government, or 2) remit compliance units.

The offset credit system would contain three elements: 1) these operational regulations, 2) federal offset protocols for running the offset program, and 3) a credit and tracking system to keep track of the trading of surplus credits.

Federal Carbon Tax Revenue

Greenhouse Gas Pricing Report 2019

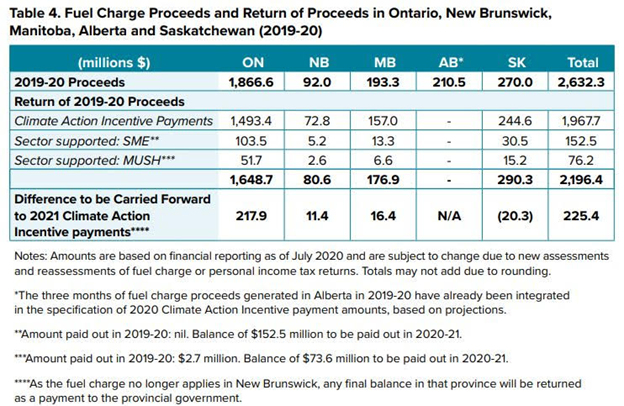

The federal government in Ottawa predicted that carbon pricing would generate around $2.3 billion in its first year fiscal year, 2019. According to the Greenhouse Gas Pricing Report for 2019, the program actually brought in $2.63 billion, exceeding the projected amount. For the 2019 year’s carbon tax credits, the government paid out $2.196 billion, leaving a difference in actual revenue of $435.9 million. Of that, the government pledged to pay back $225.4 million in tax credits. The overage meant that the federal government owed families in three of the taxed provinces — Ontario, Manitoba, and New Brunswick — over $200 million. (New Brunswick is no longer part of the federal program and uses its own carbon pricing system.)

Legal Challenges

Canada’s Supreme Court confirmed in March 2021 that the federal carbon tax is constitutional. The question was whether the federal government has the authority to force provinces to either join their program or create their own carbon pricing scheme satisfying the federal minimum standards.

The case combined three appeals related to the GGPPA: appeals courts in Ontario and Saskatchewan ruled in 2019 that the tax was constitutional — holding that Ottawa had jurisdiction to regulate greenhouse gases as a matter of national concern — but in February 2020, the Alberta Court of Appeal held to the contrary.

The three provinces argued that the federal tax program oversteps into provincial jurisdiction. In March 2021, after reserving judgment 6 months earlier, the Court held 6-3 that the tax was constitutional, ruling that Parliament has jurisdiction to enact the tax because they may “act in appropriate cases, where there is a matter of genuine national concern and where the recognition of that matter is consistent with the division of powers.” The Court noted that “influencing behavior is a valid purpose for a regulatory charge.” The decision will be watched beyond Canada’s borders and could influence other nations’ climate change action plans — especially in the United States, where the federal and state governments interact in a form of cooperative federalism similar to Canada’s.

At nearly the same time, Ontario’s Superior court struck down Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s requirement that gas stations in the province slap anti-carbon tax stickers on their fuel pumps. Ford had criticized the carbon pricing scheme as a “tax grab” and forced gas stations in the province to place a large sticker warning motorists, “The federal carbon tax will cost you,” or face a penalty up to $10,000. The law was struck down as a free speech violation, leaving gas stations free to keep the stickers or tear them off.

Meanwhile, in an infamous milestone, Canada’s Conservatives became the world’s second major political party to officially deny that human-caused climate change threatens the global environment, voting down a motion in March 2021 to recognize the climate crisis as real, as reported by The Guardian. Of course, the first such organization is the Republican Party in the United States, which has effectively held that position since 2010, and with increasing ferocity.

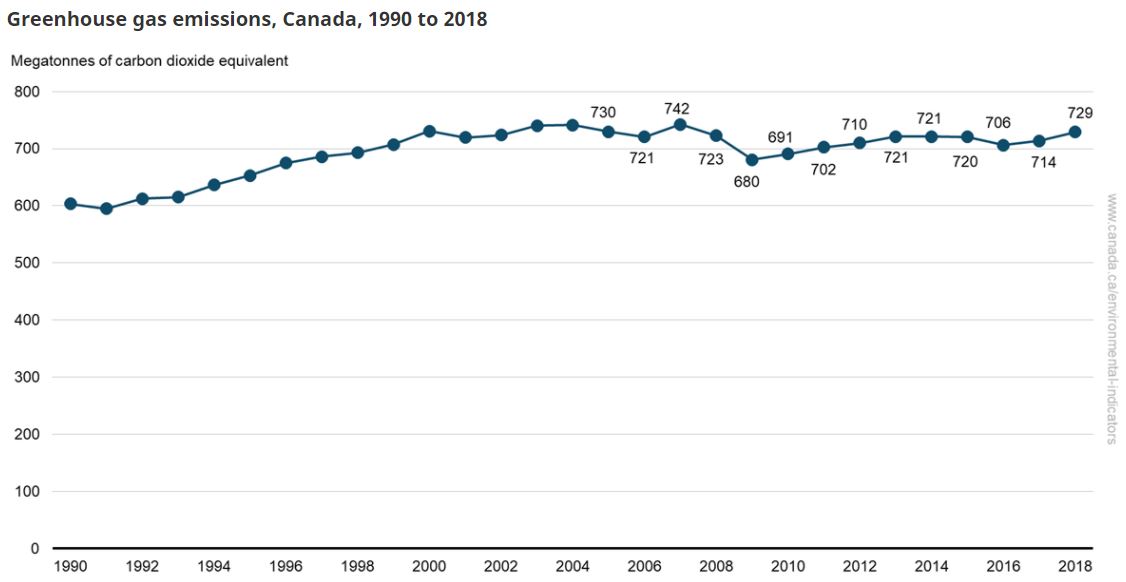

Missing the Mark

Reuters reported in Dec. 2020 that Canada, the world’s 11th largest emitter, based on 2019 data (see chart here), “has missed every one of its emissions targets.” The country isn’t on track to hit its Paris Agreement target to reduce 2030 carbon emissions by 30% below 2005 levels, to 513 megatons of CO2 equivalent. The UN Environmental Program’s UNEP’s Emissions Gap Report 2020 found that Canada would miss that target, based on recent emission trends. But the UNEP revised that finding in September 2020, saying that that the pricing measures proposed by the federal government “will allow the country to meet and exceed its target.” Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Officer estimated in 2019 that a $102/tonne tax in 2030 would be required to hit that target, but Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s proposal of $170/tonne in 2030 would far exceed that number.

The budget office warned that emissions reduction policy depends on economic growth and oil and natural gas prices: with faster real GDP growth and higher prices, a higher tax would be needed to hit the Paris target; with slower growth and lower prices, the goal would be (relatively) easily met.

Regional carbon pricing in Canada

Of Canada’s ten provinces, four had carbon pricing schemes in place before the Pan-Canadian Framework was introduced. Now, 7 provinces have their own carbon pricing systems.

British Columbia implemented its own carbon tax in 2008, and Manitoba did the same in 2012. Quebec had a carbon tax from 2007 to 2012 but shifted to a cap-and-trade system in 2012. As of February 2021, Quebec’s current tax rate is $22.40/tonne of emissions.

In 2017, Ontario implemented its own cap-and-trade program, and Alberta adopted a carbon tax program. However, Alberta–a highly carbon-dependent province–abandoned its program in 2019 and is now subject to the federal carbon tax.

British Columbia

British Columbia is Canada’s third largest province, with an estimated 2020 population of 5.1 million. It is also the fastest growing (excluding sparsely populated Prince Edward Island and Yukon Territory), with a nearly 11 percent population rise from 2016 to 2020, vs. 8 percent for the country as a whole.

B.C.’s straightforward and transparent carbon tax was North America’s first carbon pricing program. It began in 2008 at a rate of $10/tonne. The tax increased for four years by $5/tonne annually, reaching a 2012 level of $30, and stood at that level until April 1, 2019, when it was raised to its current price of $40/tonne. The provincial government announced in Spring 2020 that the rate would remain at that level until further notice due to the COVID-19 crisis.

The province’s Climate Action Tax Credit, which returns the carbon tax revenues to households, was increased for the July 2020 – June 2021 year to a maximum annual amount of $174.50 for an adult, their spouse, or their first child in a single-parent family, and a maximum of $51.25 for each additional child.

Residents of B.C. are eligible for the quarterly-issued, non-taxable credit if they are age 19 or older, have a spouse or common-law partner, or are a parent living with their child. The amount a family receives depends on the size of the family and their adjusted net income. The province also paid an additional one-time enhanced payment to families in July 2020 due to COVID-19 with increased maximum credit amounts of $218 per eligible and $64 per additional child.

This quote in Mother Jones from Clean Energy Canada’s Merran Smith helps explain the long reach of British Columbia’s carbon tax.

A 2014 Mother Jones article by journalist Chris Mooney (now at the Washington Post), British Columbia Enacted the Most Significant Carbon Tax in the Western Hemisphere. What Happened Next Is It Worked., still stands as the most digestible yet comprehensive story on B.C.’s carbon tax. Among its findings (all as of early 2014):

- The tax has brought in some $5 billion in revenue, with more than $3 billion returned in the form of business tax cuts, along with over $1 billion in personal tax breaks, and nearly $1 billion in low-income tax credits (to protect those for whom rising fuel costs could mean the greatest economic hardship).

- “Polls have shown anywhere from 55 to 65 percent support for the tax,” according to Stewart Elgie, director of the University of Ottawa’s Institute of the Environment, who added, “It would be hard to find any tax that the majority of people say they like, but the majority of people say they like this tax.”

- “Since its passage, gasoline use in British Columbia has declined seven times as much as might be expected from an equivalent rise in the market price of gas, according to a study by two researchers at the University of Ottawa. That’s apparently because the tax hasn’t just had an economic effect: It has also helped change the culture of energy use in BC.”

Emission Reductions from British Columbia’s carbon tax

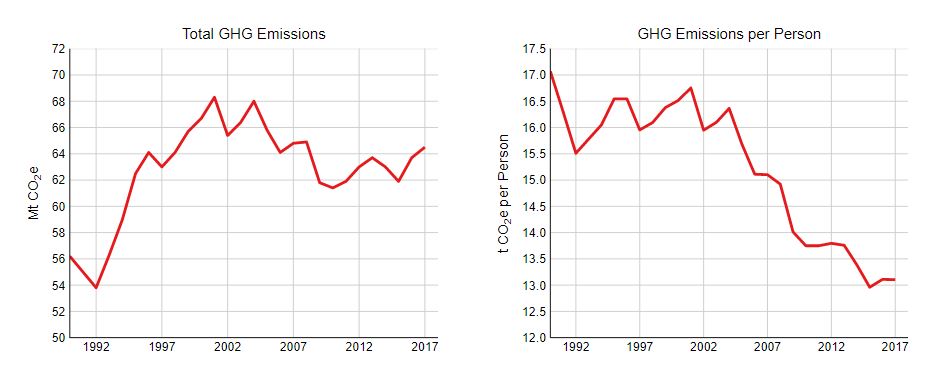

Much of the emissions reductions data in this section is from our 2015 report, British Columbia’s Carbon Tax: By The Numbers.

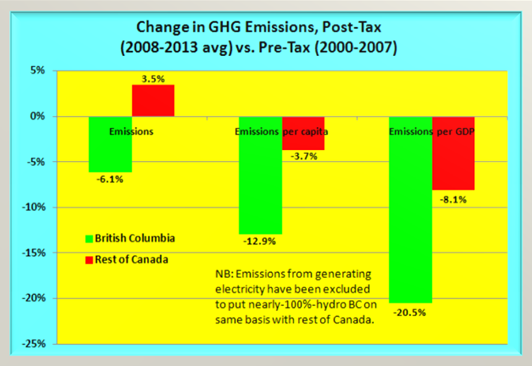

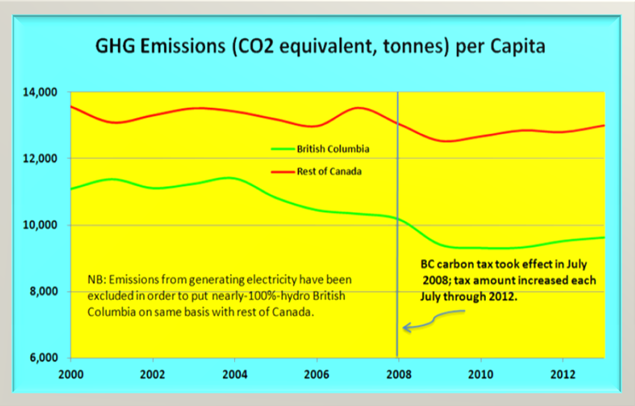

From inception of the carbon tax in 2008 to 2015, British Columbia’s per capita emissions of carbon dioxide and other taxed greenhouse gases declined, continuing a downward trend that began in 2004. Averaged across the period with the tax, 2008 through 2013, B.C.’s per capita emissions from fossil fuel combustion covered by the tax were nearly 13 percent below the average in the pre-tax period under examination (2000-2007), as shown in the graphic directly below.

The 12.9% decrease in British Columbia’s per capita emissions in 2008-2013 compared to 2000-2007 was three-and-a-half times as pronounced as the 3.7% per capita decline for the rest of Canada. This suggests that the carbon tax caused emissions in the province to be appreciably less than they would have been without the carbon tax.

These figures come with an important caveat: They exclude emissions from electricity production ― a minor emissions category for British Columbia, which draws most of its electricity from abundant (and zero-carbon) hydro-electricity, but a major emissions source for much of Canada. This sector accounted for just 2 percent of total emissions from fossil-fuel combustion in British Columbia in 2013, but for nearly 20 percent in the rest of the country. More importantly, that sector constitutes most of the “low-hanging fruit” for reducing carbon emissions, since electricity generation affords more opportunities for quickly and easily substituting low-carbon supply than any other major sector. Eliminating it from our analysis allowed us to compare changes in emissions over time on an equal basis between B.C. and the rest of the country.

In terms of total emissions (not per capita), British Columbia emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases covered by the carbon tax (but excluding the electricity sector) averaged 6.1% less in 2008-2013 than in 2000-2007. (The reduction was 6.7% when electricity emissions are counted.) The 6.1% contraction is roughly what would be expected from a small carbon tax such as British Columbia’s.

B.C.’s carbon tax does not appear to have impeded economic activity in the province. Although GDP in British Columbia grew more slowly during 2008-2013, the period with the carbon tax, than in 2000-2007, the same was true for the rest of Canada. From 2008 to 2013, GDP growth in British Columbia slightly outpaced growth in the rest of the country, with a compound annual average of 1.55% per year in British Columbia, vs. 1.48% outside of the province.

Nevertheless, GHG emissions have increased of late in British Columbia, with 2017 emissions a mere 0.5 percent less than 2007 levels. The upward trend can be attributed to three factors: 1) an 8 percent rise in oil and gas production since 2007, 2) sizeable population growth as noted earlier, and 3) the hold in the carbon tax level since 2012. This points to the necessity of raising the tax, currently at $40/tonne, to force polluters’ hand. The provincial government is planning to do so, reaching $80/tonne in 2024.

In July 2012, on the occasion of the fourth (and final) annual increase in the B.C. carbon tax, the Toronto-based Financial Post newspaper wrote of 4 key reasons why BC’s carbon tax is working. (The Post drew its text from the June 2012 report by Sustainable Prosperity, British Columbia’s Carbon Tax Shift: The First Four Years.)

- Drop in Fuel Consumption: “The carbon tax has contributed substantial environmental benefits to British Columbia (BC). Since the tax took effect in 2008, British Columbians’ use of petroleum fuels (subject to the tax) has dropped by 15.1% — and by 16.4% compared to the rest of Canada. BC’s greenhouse gas emissions have shown a similarly substantial decline (although that analysis is based on one year’s less data).”

- Growth Unaffected: “BC’s GDP growth has outpaced the rest of Canada’s (by a small amount) since the carbon tax came into effect – suggesting that it has not adversely affected the province’s economy, as some had predicted. This finding fits with evidence from seven other countries that have had similar carbon tax shifts in place for over a decade, resulting in neutral or slightly positive effects on GDP.”

- Revenue-Neutral: “The BC government has kept its promise to make the tax shift ‘revenue neutral’, meaning no net increase in taxes. In fact, to date it has returned far more in tax cuts (by over $300 million) than it has received in carbon tax revenue – resulting in a net benefit for taxpayers. BC’s personal and corporate income tax rates are now the lowest in Canada, due to the carbon tax shift.”

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions Declining: “From 2008 to 2010, BC’s per capita GHG emissions declined by 9.9% — a substantial reduction. During this period, BC’s reductions outpaced those in the rest of Canada by more than 5%.”

The New York Times, Toronto Globe & Mail, and The Guardian reported on the tax’s success in 2012 and 2014:

- July 2012 NY Times op-ed, The Most Sensible Tax of All, by economist Yoram Bauman, then a fellow at the Sightline Institute in Seattle, and Shi-Ling Hsu, law professor at Florida State University and former law professor at the University of British Columbia, and author of “The Case for a Carbon Tax” (Island Press, 2011). (Bauman later became the spearhead of Carbon Washington and its Measure I-732 Carbon Tax initiative.)

- July 2014 Toronto Globe & Mail op-ed, The shocking truth about B.C.’s carbon tax: it works.

- July 2014 op-ed in the Guardian, A carbon tax that’s good for business?, that cogently compares B.C.’s successful revenue-neutral carbon tax with Australia’s short-lived revenue-raising one.